Judges of the International Criminal Court (ICC) have deemed that South Africa flouted its duties to the Court when it failed to arrest Sudanese President Omar Al Bashir. But the judges also blamed the UN Security Council for inaction on Bashir, who has still not been arrested despite two ICC arrest warrants issued against him in 2009 and 2010. They also confirmed that there is no immunity for Heads of State who are wanted by the Court, an issue which is at the heart of its standoff with the African Union.

Not surprisingly, ICC judges on July 6 ruled that South Africa failed in its obligation to arrest Bashir in June 2015, and thus obstructed the Court in the pursuit of its functions. The Sudanese President, who is under two ICC arrest warrants for genocide and crimes against humanity in Darfur, attended an African Union summit in Johannesburg from June 13 to 15, 2015, without being troubled by the authorities. A South African court, which had been seized by an NGO, even called for Bashir’s arrest after ordering the government to stop him leaving the country. However, Bashir was able to fly off back to Khartoum, leaving South African President Jacob Zuma to face the anger of his opposition, international jurists and NGOs for having let his Sudanese counterpart escape, and for flouting the decisions of his own judges. After several months of procedures, the South African Supreme Court ruled in 2016 that the government had acted “illegally”. The ICC judges used this decision to affirm that “it has now been unequivocally established, both domestically and by this Court, that South Africa must arrest Omar Al-Bashir and surrender him to the Court”.

Diplomatic channels “futile”

Nevertheless, the Court did not refer the issue to the United Nations Security Council or to its own Assembly of States Parties. The judges considered that using the diplomatic channels available to them would be “effectively futile”, first because South Africa did in a way play the game and respect the Court. Before Bashir came to South Africa, Pretoria requested a consultation with the ICC on its obligations regarding the arrest warrants. Among the countries that have hosted Bashir, no other State has done this. Pretoria nevertheless considered that Bashir had immunity and that as host of the AU summit it could not arrest him. South Africa subsequently answered a summons to the ICC and attended the April 7, 2017 hearing to which it was called. The second reason cited by the judges is a harsh criticism of States, and especially the UN Security Council. The judges recalled that they have already referred States’ failure to cooperate six times to the UN Security Council and the ICC Assembly of States Parties. Since the ICC issued its arrest warrants against Bashir, he has travelled to numerous countries including ICC Member States like Chad, Kenya, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Djibouti. The judges added that the 24 Security Council sessions held since its March 2005 Resolution referring crimes committed in Darfur to the ICC did not lead to any concrete action against States Parties that had failed in their obligation to cooperate. So for the Court, turning to the UN would be “futile”. In an Opinion attached to the decision, French judge Marc Perrin de Brichambault went to the heart of the matter. He says that when it called South Africa to a hearing last April “the Chamber called on States and on the United Nations to respond”, but only Belgium agreed to give an opinion. “This almost total silence reflects the highly sensitive nature of the immunity issue for serving Heads of State,” the French judge continues, and the “caution” with which States handle it.

After the hearing, the head of the Coalition for the ICC, William Pace, said he shared the judges’ exasperation with the UN Security Council. "Many members of the Coalition for the ICC believe that the 124 States Parties, nearly two-thirds of the international community of nations, need to address the failures to secure arrests, and the failures of the Security Council in its referrals. These issues cannot be left to the ICC. It is the governments that must enforce arrests,” when the Council refers crimes to the ICC, he said. The Security Council can ask the Court to investigate crimes committed on the territory of States that are not ICC members, as it has done for Darfur and Libya.

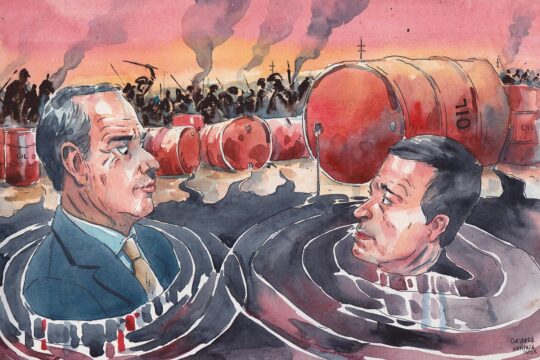

Headache

Arresting a sitting Head of State is a real headache for States, and not only African ones. In 2010, Paris moved its France-Africa summit from Egypt, where it was initially planned, to Nice, signalling to the Sudanese President that he was not welcome in France and that it preferred his absence to his arrest. Immunity for sitting Heads of State is one of the pillars of the sovereignty of nations, which has been considerably shaken by the creation of the ICC. Whilst they did not question its application, the ICC judges confirmed that this immunity does not exist before the Court, as stated explicitly by an Article of its founding Treaty, to which Members States knowingly signed up. Since the first arrest warrant for Bashir was issued in 2009, the African Union has engaged in a standoff with the Court. It first invited its members not to cooperate in the arrest of the Sudanese President. And after the Court indicted Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta, whose case was finally dropped, several Heads of State have been waging a campaign against the Court, regularly threatening to pull out of it. The South African government threatened withdrawal last October, without the approval of its parliament. Although the Supreme Court opposed the move in February 2017, President Jacob Zuma this week reiterated his decision. South Africa’s departure from the ICC will in principle be effective next October. And the Southern Africa Litigation Centre (SALC), which initiated national procedures against the government in the Bashir case, thinks that if the ICC did not want to go to the UN Security Council, it was to appease Pretoria. “We understand this in light of the sensibilities around South Africa’s membership of the ICC,” explained its executive director Kaajal Ramjathan-Keogh. It is still too soon to know if the Security Council and the Assembly of States Parties will hear the judges’ decision. In the meantime, Omar Al Bashir is due to go to Russia in August at the invitation of Vladimir Putin. Russia, which is targeted in an investigation opened by the ICC Prosecutor in 2016 on the 2008 war in Georgia, announced in November that it would not ratify the ICC treaty. Thus it is not under an obligation to cooperate with the Court. But Russia is nevertheless one of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council which asked the Court to intervene on Darfur.