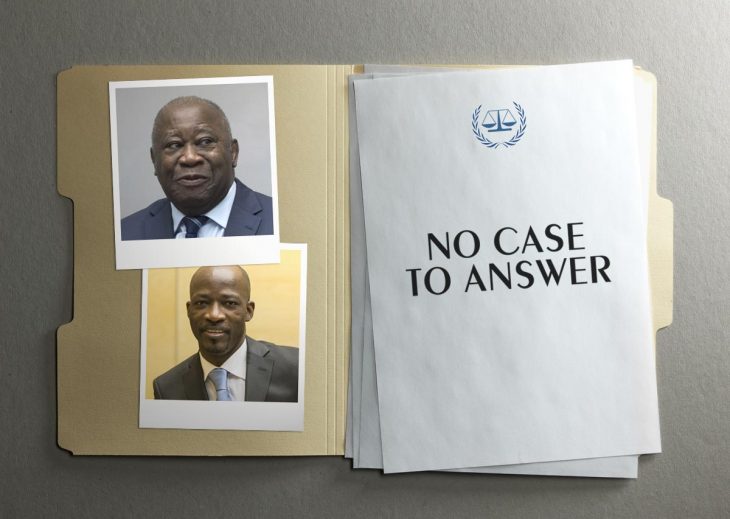

Evidence of "exceptional weakness". This is how Presiding Judge Cuno Tarfusser describes the case of the International Criminal Court (ICC) Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda against former Ivorian President Laurent Gbagbo and his Minister of Youth Charles Blé Goudé. In 2018, then accused of crimes against humanity, the two men had filed a "no case to answer" request: their defence teams considered that the prosecution file presented over the past two years did not require the defence to present its arguments to obtain the withdrawal of the charges.

A withdrawal that was obtained last January by an oral decision of the majority of the Trial Chamber, with the promise to give a "fully reasoned decision as soon as possible". Seven months later, on 16 July, the same chamber published its "reasons for oral decision". In fact, it is a nine-page document outlining the steps in the proceedings and referring to three appendices: the reasons presented by Judge Geoffrey Henderson (Appendix B), the opinion of Judge Cuno Tarfusser (Appendix A) and the dissenting opinion of Judge Olga Herrera-Carbuccia (Appendix C).

Italian-style settling of scores

Thus, the majority of the Chamber, Tarfusser and Henderson, did not issue a joint reasoned decision as such. The former only relies on the reasoning of the latter (961 pages) while publishing a 90-page opinion in which he gives a very critical judgment of the prosecutor's work, and to a lesser extent of the defence's work. For the President of the Chamber, Gbagbo and Blé Goudé must be acquitted on the basis of "an in-depth analysis of the evidence" and of "its exceptional weakness". He recounts "sifting through mountains of documents purportedly supporting that case, none of which could confirm it in the slightest".

The text of the President of the Chamber is also an opportunity to speak about him in the first person. "The reasons for this opinion are rooted in the profound differences between my legal background and approach and the ones of my fellow judges," he explains on the second page, before using the pronoun "I" over and over again - something that the other two judges have avoided tactfully. Italian judge Tarfusser seems to be clumsily settling scores with the prosecutor and with the functioning of the ICC, while judge Henderson's opinion, ten times longer, is much more sober and delicate - to achieve the same result: acquittal.

Putting the cart in front of the horse

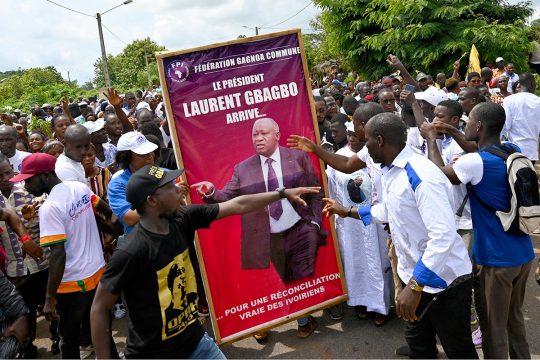

To achieve this, the majority first analyzed the vision of Côte d'Ivoire presented by the prosecutor's office. A vision described by Tarfusser as "relying on shaky and doubtful bases, inspired by a Manichean and simplistic narrative of an Ivory Coast depicted as a ‘polarised’ society where one could draw a clear-cut line between the ‘pro-Gbagbo’, on the one hand, and the ‘pro-Ouattara’, on the other hand". For Justice Henderson, Prosecutor Bensouda "systematically omits or downplays significant elements of the political and military situation", which has resulted in "a somewhat skewed version of events". The judges believe that the prosecutor decided on a theory and then tried to apply evidence to it to support her version of the facts - when the latter should have been the basis of the theory. In short, we wanted to put "the cart in front of the horse", according to the words of the judge from Trinidad and Tobago.

No common plan

At the “no case to answer” stage, judges do not normally have to assess the authenticity of the evidence - but the case presented being what it was, they made many remarks about the origins of documents and the use of testimony. For crimes to qualify as "crimes against humanity", it is necessary to prove the existence of a common plan and/or a policy of large-scale or systematic attack.

Justice Henderson summarizes the prosecutor's failure to prove the existence of a common plan in the following paragraphs: « The difficulty with the Prosecutor’s approach is that none of the individual factual elements she relies upon. clearly point to the existence of a plan or policy to attack civilians. The Prosecutor acknowledges this but argues that when all the different strands of her argument are considered together, it becomes clear that the Common Plan and the policy were criminal in nature… While it is true that the (criminal) content of the Common Plan can, in principle, be inferred from a combination of circumstantial evidence, this theoretical possibility does not relieve the Prosecutor from formulating a cogent argument in this regard… Ultimately, the Prosecutor bears the burden of demonstrating, for each factual allegation she makes, which evidence purportedly proves it. If it is a combination of evidence that allegedly proves a fact, then the Prosecutor must clearly identify all the pieces of the puzzle and, crucially, explain how they fit together. »

For example, Henderson explains that "meetings between the members of the alleged 'inner circle' and the accused discussed hereinabove shows that there were relatively frequent contacts between different members of Mr Gbagbo's government as well as senior FDS officers. This does indeed show that there was frequent communication and a certain level of coordination. However, there is nothing unexpected about this. No government can function without a minimum level of communication and coordination. »

No evidence of attack targeting civilians

The majority of the Chamber therefore considers that the existence of a common plan to attack civilians is not proven. It goes even further: the documents presented by Bensouda’s team do not allow to say that the attacks specifically selected in this case targeted civilians. It would be "utterly irresponsible to make any findings about what allegedly happened during the RTI march [Radio-télévision ivoirienne, the national TV and radio network]" on the basis of the prosecution evidence, writes Henderson about the December 2010 demonstration against Gbagbo's decision to remain in power. The prosecutor alleged that the FDS had violently repressed the demonstration and that the victims had been targeted because they were perceived as "actual or perceived political activists or sympathisers, or civilians who were considered to be supporters of the opposition due to their Muslim faith, Dioula ethnicity and/or their provenance from northern Côte d'Ivoire, or other West African countries. »

Another example is the march of women in Abobo commune, where 13 of them were killed on 3 March 2011 by the FDS, according to the prosecutor (who relies on a video and accounts from witnesses and experts). For Henderson, "although serious question marks may be placed by the use of a heavy machine gun in an environment with a very high concentration of civilians, it is not possible to determine on the basis of the available evidence that the soldiers in the BTR 80 or in any of the other vehicles in the convoy caused the deaths and injuries of the 13 victims of the women's march".

No criminal liability

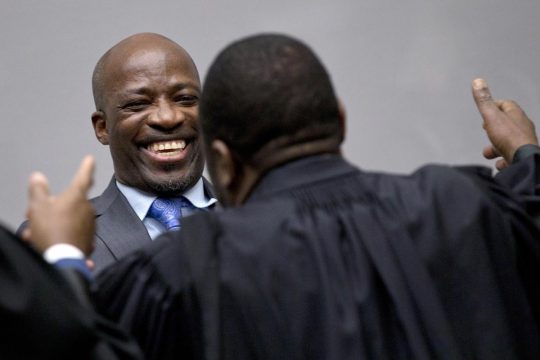

Even if the Chamber had considered that there had been crimes against humanity committed in Abidjan during the post-electoral crisis of 2010/2011, the prosecutor would have had to demonstrate the responsibility of Gbagbo and Blé Goudé in the commission of these attacks. For Henderson and Tarfusser, Bensouda failed here too. "No witness was in a position to say that he had personally attended a speech by Charles Blé Goudé, where he would have incited or encouraged or otherwise condoned violence against political opponents, or otherwise; nor can this be inferred from the video recordings submitted," wrote the presiding judge to illustrate the absence of responsibility, before adding: "Far more frequent are the instances where either Mr Gbagbo or Mr Blé Goudé, as well as members of their alleged 'Inner Circle', are on record as explicitly advocating peace or denouncing violence. »

In our article to be published this Thursday, we will explain why Judge Olga Herrera-Carbuccia, who issued a dissenting opinion to that of the majority of the Chamber, does not agree.