“We regret that efforts by the UN Security Council to refer the situation in Syria to the International Criminal Court continue to be blocked. We therefore continue to consult with other countries and relevant actors on the possibility of establishing an international tribunal or similar mechanism, as a complement to national prosecutions,” Swedish Home Affairs Minister Mikael Damberg told JusticeInfo via E-mail. He hosted a meeting in Stockholm in early June to discuss the issue, attended by 11 European Union countries including the UK, France and Germany, plus Switzerland, but “no decisions were taken”, according to Swiss foreign ministry spokesman Pierre-Alain Eltschinger.

The head of the UN special probe into IS crimes in Iraq, British lawyer Karim Khan, is also one of those calling for Nuremberg-style trials for IS to ensure their ideology is “debunked”. “Iraq and humanity requires its Nuremberg moment,” he told the AFP news agency. A fair trial for IS “can also contribute to separating the poison of IS from the Sunni community” and have an “educative effect, not only in the region, but in other parts of the world where communities may be vulnerable to the lies and propaganda of IS”.

“We want the whole view”

After capturing the last IS stronghold in Baghouz, Syria, in March, Kurdish-led forces in the northeast of the country are holding tens of thousands of people linked to IS in camps in their autonomous zone. They have appealed for help to try them, and also for Western States to take their IS-linked people back, but so far to little effect. Most Western countries are unwilling to actively repatriate their citizens who went to join IS, and the UK has even started stripping some of their citizenship. IS suspects are also being held in Iraq, and rights groups have expressed concerns about fair trial and detention conditions in both countries. Hence the idea of an international tribunal.

But Syrian lawyer and human rights activist Mazen Darwish, founder of the Violations Documentation Center, says an international court for just IS is a “very bad idea”, and his organisation has written to the Swedish government expressing this view. Whilst not opposed in principle to the idea of an international tribunal, he told JusticeInfo that it should have a mandate to try all parties involved in the Syrian conflict, “especially the Syrian government”, otherwise it could send a bad message and “establish impunity for other crimes”. He acknowledged the urgency of the situation, saying such a court could perhaps “start trying IS crimes first” but that “we want the whole view” and any other way would risk perpetuating conflict in the region.

A hybrid model?

Damberg has said that such a tribunal might be modelled on the UN’s ad hoc tribunals for former Yugoslavia and Rwanda. But international criminal lawyers who spoke to JusticeInfo were sceptical, pointing to the fact that those tribunals were extremely slow, expensive and only tried a relatively limited number of individuals.

French Justice Minister Nicole Belloubet has stressed that an international tribunal is a “hypothesis” under discussion, but that it should be created “on the spot, undoubtedly not in Syria, perhaps in Iraq” and could operate with “European, French and Iraqi judges”. “It would need the agreement of the Iraqi State, and the necessary conditions, notably on the death penalty which should be banned,” she said.

Iraq is already holding trials under its anti-terrorism laws of IS members, including some foreign ones. Death penalty is a primary concern. Eleven French nationals have already been sentenced to death in Iraq for belonging to IS, although these sentences have not been carried out.

Marco Sassoli, director of the Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights, thinks it is likely that Iraq would agree to a mixed tribunal applying international standards and no death penalty in exchange for significant Western help with expertise and infrastructure. “Iraq wants to have and has started to have trials of local fighters and also some foreign ones and they would be happy, if they get enough money, to establish a mixed tribunal like we did for Lebanon,” he said.

Victims’ concerns

Kurdish forces in northeast Syria have appealed for international support to try IS detainees under their own judicial system, but Sassoli says this would be “revolutionary” because it would mean establishing an international court in a country [Syria] that did not consent. Extending such support to these Kurdish forces would also be a “form of recognition” of people that Syria and Turkey regard as rebels

Natia Navrouzov, who heads the documentation project at the Yazidi organisation Yazda, says Yazidi victims she has worked with generally want an international tribunal in Europe to see IS perpetrators tried, because they do not trust either the Iraqi or Kurdish authorities to deliver justice for them. They want international criminal justice to recognise genocide against the Yazidi and they “always make the comparison with Rwanda”.

Darwish, who has been imprisoned by the Syrian regime, also says Europe would be the best location to ensure that there is no death penalty; an independent, professional court; defence rights; and “victims can be present”. But he thinks this is not what European States want because they “don’t want to receive their fighters” and “don’t want to face the problem”. The States concerned insist a tribunal near to the scene of the crimes would be more efficient because, as Damberg told JusticeInfo, “that’s often where the evidence and victims are”. Darwish thinks the countries concerned should live up to their responsibilities, take their citizens back and try them under their own jurisdictions.

Iraq’s uncertainties

As Iraq seems to be the favoured option for now, Navrouzov of Yazda says they could be happy about it “if there’s some capacity building in Iraq”. But she worries about some of the challenges. “Will international judges and lawyers agree to come here? Iraqi criminal law does not recognise genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity, which from our point of view is something that happened to the Yazidis, so there would be many practical challenges.”

According to Darwish, victims don’t trust the Iraqi authorities and “we don’t know how independent [the tribunal] would be”, given that Iraq is also “in a kind of civil war” and everything is linked to politics.

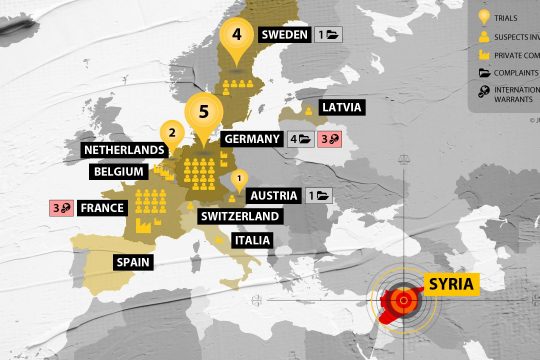

“My feeling is that this whole idea of an international tribunal will finally not work,” says Sassoli. Meanwhile, Navrouzov stresses that her organisation is sharing information with prosecutors in France and Germany. A number of European countries have started to prosecute crimes related to Syria, notably Germany, France, Sweden and the Netherlands. “We don’t want to wait”, says Navrouzov.