The first week of Roger Lumbala’s trial ended with an unexpected legal challenge: how to fill the void left by an absent accused and defence. The former Congolese rebel leader refuses to appear in court and demands that his defence team – which is also absent – remain silent. In addition to the charges against him, he strongly contests the French court’s competence to try him for crimes committed thousands of kilometres away in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). This was raised by his four lawyers at the opening of the trial on Wednesday November 12 before the Paris Assize Court, to which this case was referred under the principle of universal jurisdiction. But without waiting for the judges’ decision, Lumbala embarked on a strategy of total boycott: he requested not to appear in court, denounced a “judicial hijacking”, and dismissed his lawyers. In short, he declared, “you will be trying me on your own”.

Roger Lumbala, 67, is being prosecuted for “participation in a criminal conspiracy to commit crimes against humanity” and “complicity in crimes against humanity” for acts committed in the north-east of the DRC between 2002 and 2003. More specifically the French courts accuse him, in his capacity as president of the Congolese Rally for Democracy-National (RCD-N), of having “incited” and “allowed” his fighters to commit massacres, rapes, acts of torture and enslavement of civilian populations in the provinces of Ituri and Haut-Uélé. These abuses were perpetrated during Operation “Effacer le tableau” (Wipe the Slate Clean), carried out jointly with the Movement for the Liberation of Congo (MLC) of Jean-Pierre Bemba, a central figure in the Congo wars and now Deputy Prime Minister of the DRC. But Lumbala does not intend to face these charges. Since making his statement he has not reappeared in the courtroom, although the trial is continuing.

Every morning, the man is taken to the Paris court from his prison cell, where he has been held since his arrest in December 2020. There, from the cells located in the basement of the courthouse, he can choose to appear in court or not. On November 14, in a message sent to the court, he reaffirmed his refusal to recognize the jurisdiction of the court, and upped the stakes by saying he would go on hunger strike.

A trial without the defence

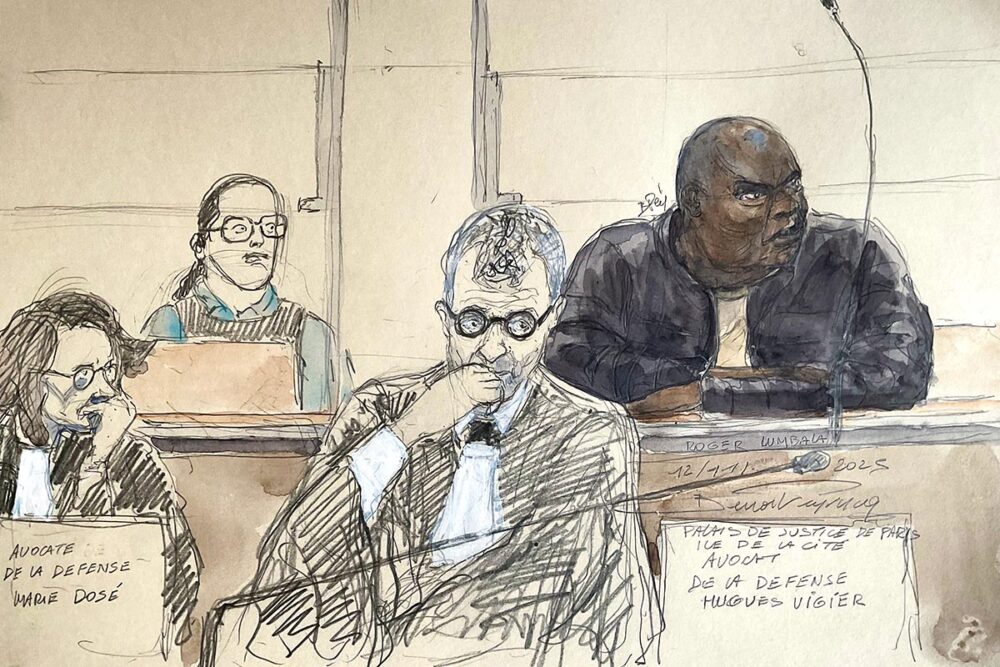

This announcement prompted a meeting between Lumbala and Hugues Vigier, a lawyer who was initially part of the team assigned to defend him, but who was then made his court-appointed lawyer, a role he did not want. Surprised by the collective recusal of the defence team, Vigier initially declined this role, believing he could not represent a man who did not want to be represented. But the reason for recusal was not accepted by court president Marc Sommerer.

In the days that followed, however, the defence bench remained empty. Like the accused, the lawyer did not appear at the hearings. When contacted by Justice Info, Vigier said he was “aware” he risked disciplinary proceedings – the presence of a lawyer in a criminal trial is mandatory – but wanted to remain “consistent”. “Lumbala expressly stated that he did not want to participate in the trial and did not want to be represented,” he said. “If I intervene, he is the one who risks prosecuting me before the Bar Council for breach of my mandate. I can’t stay in court facing opposing parties for more than five weeks without being able to speak, just to give an impression of balance, as if there were indeed equality of arms. That is not why I am here, [...] and I cannot condone it. Because I believe, after all, that my oath has meaning. I am here to assist, advise and defend.” Vigier nevertheless indicates that he is prepared to return and defend his client’s interests if Lumbala were to change his position, which, he believes, “he has no intention of doing.”

In a joint statement, several organisations that have joined the case as civil parties expressed their “concern about these developments”. In their view, the “steps” taken by Lumbala “appear intended to destabilize the survivors before they testify, and to obstruct a legal process they have been awaiting for more than 20 years”.

Vigier says he does not know why the man he is asked to defend has embarked on such a strategy, even before a decision has been made on the question of jurisdiction – which is taking a long time. Perhaps Lumbala felt he had been judged in advance, the lawyer speculated. Before the Court, the accused particularly criticised the fact that he, “an African in the dock”, was being tried by French people “who know nothing about the situation in the DRC”. Lumbala complained that he was not being defended by a lawyer from his own country. A Congolese lawyer did appear at the opening of his trial, but was not allowed to join his defence team because he had not completed the necessary formalities. “What we may have overlooked,” continued Vigier, “is that Lumbala is still posing as a politician and that during the hearing he found a platform. This is a role he undoubtedly plays with sincerity, but one to which he did not accustom us in the confidentiality of the visiting room.”

Rebel leader or politician?

However, it is precisely on Lumbala the politician that his entire defence has been built. Since his arrest, the former warlord, who became Minister of Foreign Trade between 2003 and 2005, has consistently proclaimed his innocence, repeatedly asserting that the RCD-N, of which he was president, was merely a “political movement” and that he had “no troops” under his command. According to him, the combatants involved in the acts of which he is accused were in fact obeying Jean-Pierre Bemba, the strongman of the MLC.

At the opening of the trial, almost two full days were initially set aside for Lumbala’s testimony. He was to be questioned at length and confronted with the various elements in the case file, supported by several UN reports focusing mainly on the illegal exploitation of the Congo’s rich resources and the abuses committed there. In the end, it took only a few hours to read the evidence and hear the character witness. Clearly uncomfortable with the task imposed on him, the presiding judge repeatedly pointed out that when there is no one to defend the accused, “things are a bit unbalanced”.

We know almost nothing of why Lumbala became involved in politics, except that he says he wanted at an early age to get involved in “social progress” because he wanted to “change things”, not to gain any personal benefit. But he also added that he did not succeed. Similarly, there is little evidence to portray the political ideas he may have defended. At the hearing, Thierry Vircoulon, a researcher at the French Institute of International Relations (IFRI) and specialist on central Africa, said that at that time, most rebel groups presented themselves as political movements, but in reality they were made up of “disenfranchised men” who had no real political programme other than the desire to gain power “to prevent the destruction of the country”. This observation supports the hypothesis of the civil parties’ lawyers, for whom Lumbala’s winding political career illustrates his “opportunism” rather than a genuine adherence to a political ideology.

An opponent’s journey

What we do know is that for Lumbala, it all began in the 1980s. That was when he joined the Union for Democracy and Social Progress (UDPS), the main opposition party to Mobutu See Seko’s dictatorship. This was a movement that he himself described as “pacifist”, founded and led by Étienne Tshisekedi, his “mentor”. But after spending some time campaigning in Kinshasa, the young man feared for his safety. He fled with his family to France, where he was granted political asylum. He did not give up his commitment, however, as he chaired one of the French branches of the UDPS in Rennes.

During this period, he reportedly worked in a warehouse and hosted a diocesan radio programme before moving to the Paris region, where he briefly worked as a financial advisor for an insurance company. In 1997, he gave it all up to answer the call made to Congolese diaspora by Laurent-Désiré Kabila, leader of the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo (AFDL) – supported and armed by Rwanda –, who had just seized Kinshasa and proclaimed himself president. Lumbala was still dreaming of a career in politics and saw this as an opportunity to join the new government. But he got nothing.

The following year, a new war broke out in what was no longer Zaire but the Democratic Republic of Congo. Kabila asked his allies, Rwanda and Uganda, to withdraw their troops from the country. Lumbala, a new opponent of Kabila, joined the rebellion. In 1998, he helped create the Congolese Rally for Democracy (RCD), supported by the two countries that had brought Kabila to power and were now his enemies. Lumbala held relatively important positions within the RCD, but dissension arose and several dissident armed groups formed. Lumbala joined one, then another, before being arrested. After his release, he went to Kampala, the Ugandan capital, where he surrounded himself with new influential supporters. With their financial and material support, he established himself in the territory of Bafwasende, in the gold and diamond-rich north-east of the DRC, and founded the RCD-National (RCD-N). He described this movement to character investigator as a “politico-military” group.

Lumbala forged alliances, particularly with the more powerful Bemba, whom he also considered his “mentor”. In 2002, they together launched Operation “Effacer le tableau” (Wipe the Slate Clean) around the town of Mambasa. Their objectives were to oust a pro-government faction and take control of the region’s mining areas.

He becomes a minister, then exiled again

In 2003, the signing of a peace agreement between Joseph Kabila – who became president of the DRC after his father was assassinated in 2001 – and rebel groups established a transitional government. Bemba held the position of vice-president. Lumbala joined the government. But in 2005, he was implicated in corruption cases and was dismissed. In 2008 Bemba, who had also fallen from grace, was arrested in Europe, tried and convicted by the International Criminal Court for crimes committed in the Central African Republic, before being acquitted on appeal.

Lumbala, meanwhile, continued his political career. He was elected deputy for Kasai, his native region, and then became a senator. In 2011, he supported Tshisekedi’s presidential bid. But the following year, he was once again forced into exile, accused of treason for supporting the March 23 Movement (M23), a new armed rebel group backed by Rwanda and particularly active to this day in eastern DRC.

In France, he again applied for asylum. This time, however, his request was denied on the grounds of abuses committed and documented by fighters belonging to the RCD-N, which he led. It was a report by the French Office for the Protection of Refugees and Stateless Persons (OFPRA) that led to the opening of a preliminary investigation in 2016 into the allegations against him. And in December 2020, Lumbala was finally arrested near his home in the 13th arrondissement of Paris.

To complete the picture, we should also mention one last allegiance. Shortly before his arrest, Lumbala founded the “Base de la République” platform to support his former rival Félix Tshisekedi, now President of the DRC, who is none other than the son of his former ally, Étienne Tshisekedi.

Clémence Bectarte, one of the lawyers representing the civil parties, thinks his rapprochement with Tshisekedi’s son, like his ties to Bemba – who became deputy prime minister in the new government – could enable the former warlord to avoid ever answering for the charges against him in this trial. None of the many crimes committed in the DRC between 1998 and 2003 have been tried. On this at least, the Lumbala trial should break the silence.