A “long”, “complex”, and “gigantic” process. These are often the terms used to describe the eight years of investigation into the Lafarge case. And the trial that opens this Tuesday, 4 November 2025 is unlikely to mark the end of it. The French cement manufacturer is to appear until 16 December 2025 before the Paris Criminal Court, where it is charged with “financing terrorist enterprises” and “failure to comply with international financial sanctions”. In this case, Lafarge is accused of paying €5 million to several terrorist organizations between 2013 and 2014 through its Syrian subsidiary. These payments were intended to ensure the continuation of its activities in the country.

The trial is unprecedented: never before has a multinational corporation been brought to justice for such acts as a legal entity.

Plea bargain in the US

In 2022, Lafarge - which had since merged with the Swiss group Holcim - admitted to financing terrorist organizations as part of a plea bargain signed in the United States. The group had to pay a $778 million fine, thus ending US proceedings. These admissions only implicate the legal entity; the eight individuals brought before the French courts were not involved in the proceedings – although this could undermine their presumption of innocence, according to one of their lawyers.

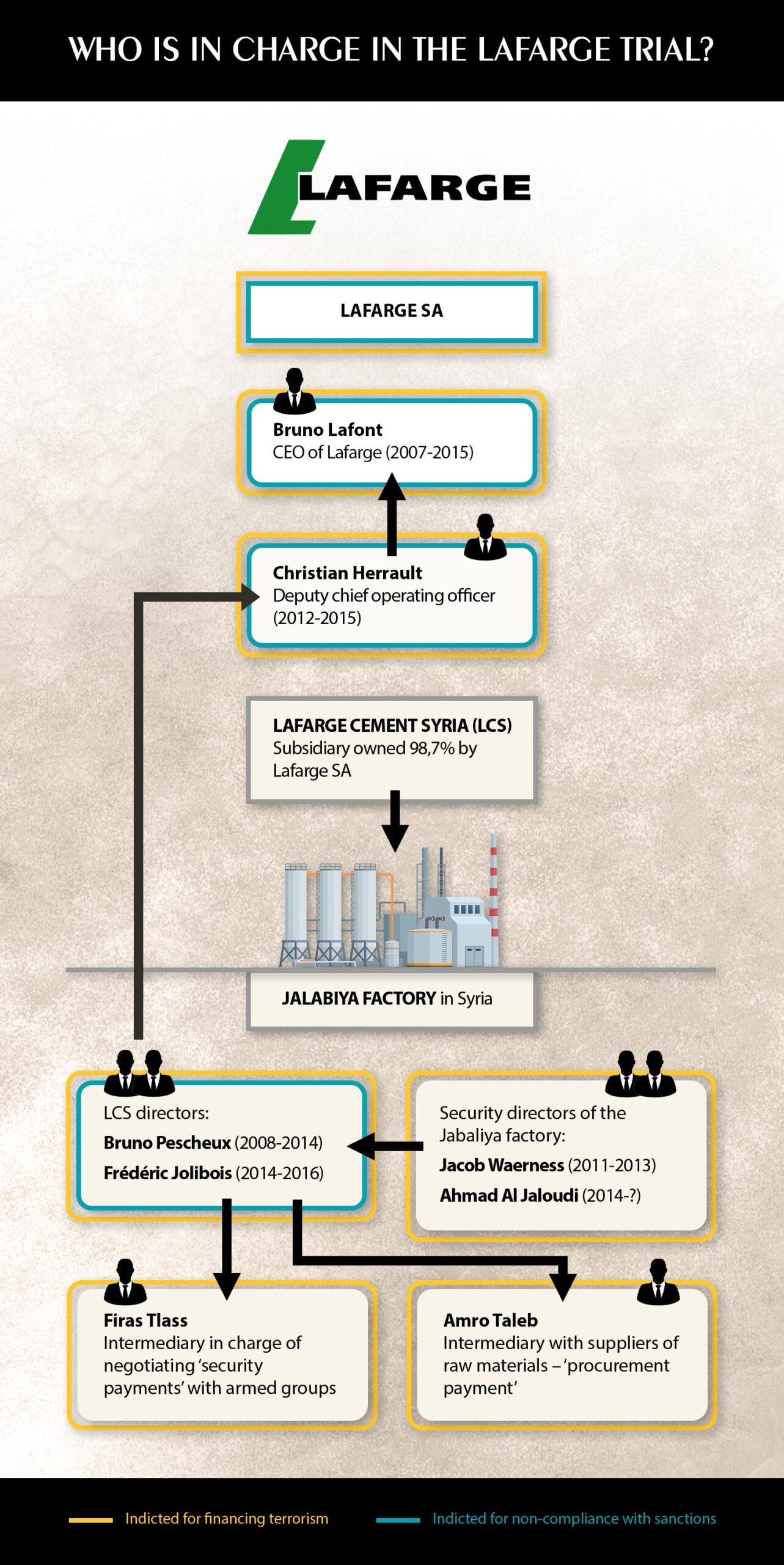

Among them, four French former executives of Lafarge and its Syrian subsidiary will be tried for “financing terrorist enterprises” and “failure to comply with international financial sanctions”: Bruno Lafont, CEO of the group until 2015; Christian Hérault, then deputy chief operating officer; Bruno Pescheux and Frédéric Jolibois, former directors of the Syrian subsidiary, Lafarge Cement Syria (LCS). Alongside them, a Norwegian, Jacob Waerness, a Jordanian, Ahmad al Jaloudi, a Syrian, Firas Tlass, and a Syrian-American, Amro Taleb, all of whom operated in Syria on behalf of Lafarge, will appear in court on the sole charge of “financing terrorist enterprises”.

However, the trial does not cover all of the charges against Lafarge: in this case, the company has also been charged with “complicity in crimes against humanity.” Initially examined as part of the same judicial investigation, this charge was separated in 2023. The investigation into this aspect of the case is ongoing.

This decision, to split the case in two, weighs heavily on the civil parties, including some 200 former employees of the Syrian cement plant, who are aware that this separation will delay the trial they are awaiting. Élise Le Gall, a lawyer representing some of these employees, nevertheless wants to view this first step as “an opportunity to obtain additional information that will be useful in the ongoing investigation”. But for her, it is also an opportunity to focus on the multinational’s “financial spiral”.

“Security payments” to the organization Islamic State

It all started at the Jalabiya plant. The cement factory, located in northeastern Syria, was still under construction when it was acquired by Lafarge in 2007, following the takeover of Orascom Cement, an Egyptian cement company. The investment opened up new markets for the manufacturer - particularly in the Middle East and Africa - but it also increased its debt. So, in 2010, when the Syrian factory finally went into operation in a region where demand for cement was set to grow rapidly, Lafarge expected a return on its investment.

But in 2011, the Syrian revolution broke out. Within a few months, the country was plunged into civil war. Despite the instability, Lafarge’s management decided to maintain production. The cement plant was managed by Lafarge Cement Syria, a subsidiary 98.7% owned by the group. It was not until July 2012, when all French companies in Syria had already ceased operations, that Lafarge began to prepare for the gradual evacuation of its foreign employees. Syrian employees, however, continued to work.

It was then, as armed groups fought over the region, that Lafarge and LCS allegedly began negotiations to guarantee access for trucks and employees to the factory, but also their release in the event of kidnapping or arrest. These so-called “security” payments - initially made to rebels of the Free Syrian Army and Kurdish fighters - quickly benefited several groups deemed as terrorists, which were gradually gaining influence.

Between 2013 and 2014, the French investigating judges estimate that Lafarge transferred €3.1 million in “security payments” to the organization Islamic State (IS), to Jabhat al-Nosra, and to Ahrar al-Sham. They also estimate that the company “injected” nearly €1.9 million into the local economy by purchasing raw materials (pozzolan, sand, petroleum hydrocarbons) from suppliers “under the control of Islamic State”. The transactions were taxed at 10% by the jihadists: approximately €187,000 is believed to have been paid directly to the organization in taxes.

Resumption of activity after the proclamation of a caliphate

In the summer of 2014, the situation became untenable. According to the referral order consulted by Justice Info, the factory closed its doors. But it reopened in early September, after reaching, according to the investigating magistrates, a financial agreement with the organization IS, “supposed to be valid until February 2015”. The court document indicates that the sum paid at that time came several weeks after the organization IS proclaimed a caliphate on 29 June 29 2014, and the adoption on 15 August 2014 of a UN Security Council resolution condemning “any direct or indirect trade with the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, the al-Nusra Front, and all other individuals, groups, undertakings, and entities associated with al-Qaeda”.

However, on 18 September 2014, while some 30 employees continued to run the cement plant, the jihadist group threatened the region - and the industrial site - with an imminent assault. A few days later, Lafarge told the press that the plant had been shut down and the staff evacuated. In reality, “no manager told us to leave,” said a former LCS employee interviewed by Justine Augier in a book entitled Personne morale. Faced with the imminent attack, employees were forced to flee by their own means: “If we had left an hour later, Daesh would have cut off our heads. [...] Lafarge didn’t care. We just ran away. It’s too hard for me to remember that moment,” this employee said. Three days later, a jihadist propaganda video was released showing the Jalabiya cement plant in the hands of the organization IS. Four employees were captured and held hostage for ten days before being released.

Two years later, the story broke in the press: in February 2016, on the Syrian news site Zaman Al Wasl; and in Le Monde, in June of the same year. Two complaints are filed. It is the starting point of a long legal battle.

Lafarge’s “historic” indictment as a legal entity

In September 2016, the French ministry of Economy and Finance filed the first complaint, accusing the company of violating the embargo imposed on Syria by the European Union. This embargo prohibited any financial or commercial relations with the Syrian regime and groups subject to sanctions, including the organization IS. Two months later, a second complaint was filed with the national anti-terrorism prosecutor’s office by eleven Syrian employees and two non-governmental organizations: Sherpa and the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR). It targeted Lafarge, its Syrian subsidiary (LCS) and several of its executives for “complicity in crimes against humanity”, “financing terrorist enterprises”, “deliberately endangering the lives of others” and other related offenses.

In June 2017, a judicial investigation was opened, leading to the indictment of several former executives of the French cement company. But it was in June 2018 that the case took on a whole new dimension, when Lafarge SA itself was indicted as a legal entity for “complicity in crimes against humanity”. “This is undoubtedly the most historic and important aspect of this entire proceeding,” says Anna Kiefer, litigation and advocacy officer at Sherpa. For the first time, investigating judges ruled that “criminal responsibility for international crimes should not rest solely with individuals,” but with the company itself. This is a major legal precedent, agrees Cannelle Lavite, co-director of the Business and Human Rights Department at ECCHR, as it “demonstrates above all that it is possible to criminalize a parent company” for acts committed by one of its subsidiaries abroad. This contributes to “deconstructing the discourse of executives” who, according to the lawyer, “very often hide behind their subsidiaries,” even though “they control them through capital and hierarchical structures” and despite the fact that they “derive income” from them.

These indictments have been the subject of numerous appeals. But after several years of “legal twists and turns,” which we reported on in 2022 on the Justice Info's website, Lafarge’s indictment as a legal entity was definitively confirmed by the Court of Cassation on 16 January 2024.

A victory and setbacks for the civil parties

For the civil parties, the decision of France’s highest court is as much a victory as it is a huge setback. Because in the same ruling, the judges overturned the indictments for “endangering the lives of others”. The Court of Cassation ruled that Syrian employees of LCS could not benefit from the protections provided by French labor law. It held that the contracts were governed by Syrian law, since the main employment relationship was in Syria.

But the consequences of this annulment go further for the 200 or so employees who had brought civil proceedings. “Endangering the lives of others” was the only other basis - along with “complicity in crimes against humanity” - that allowed workers to hope for possible compensation for the damage suffered. In fact, in another decision handed down by the Court of Cassation on 20 April 2022, the judges had ruled that their civil action on the grounds of financing terrorism was inadmissible. “What the ruling tells us is that this offense is, by its very nature, detrimental to the public interest and cannot constitute direct and personal harm to any individual. But it does not take into account the specific nature of the plaintiffs’ situation and the direct and personal harm they suffered as a result of these acts of illegal financing,” explains lawyer Matthieu Bagard, alongside Le Gall.

Together, they represent some 60 former employees of the Jalabiya factory. And they intend to challenge this interpretation as soon as the trial begins. The “link” between the danger they faced and the financing of terrorist groups is clear, according to Le Gall: "Every day, LCS employees traveled to the Jalabiya factory, passing through checkpoints manned by armed rebel groups, but also terrorists, whom Lafarge financed to ensure traffic flow. These journeys had become a constant threat to them: they were stopped, questioned, sometimes detained or kidnapped. Their lives literally depended on the payments made by the company to these groups to keep the roads open. Without this financing system, they would have never been exposed to this danger. The offense of financing a terrorist enterprise immediately created the very conditions for the harm they suffered.”

And for LCS employees, the issue of compensation is particularly important. Because while their status as civil parties is still “admissible” in the investigation for “complicity in crimes against humanity,” there is no guarantee that a second trial will take place. However, Bagard adds, “we can see that, twelve years after the events, Lafarge has recovered fairly well from its legal setbacks,” but that many workers “remain in extremely precarious situations” and are “unable to find work,” whether in Syria or abroad.

For the civil parties, the main issue at stake in the hearing that opens on Tuesday in Paris is precisely this: to ensure that the employees of the Jalabiya cement plant are heard in this first trial and considered. “The debates, which the defense can sometimes make technical, must not obscure the real impacts on people who have not been properly protected,” Lavite insists.

On the role of the French authorities

Beyond the criminal responsibilities of the group and its managers, the trial could shed light on certain gray areas. In particular, the role of the French authorities in this case. In recent years, the investigation has established that some Lafarge executives passed on information to the French intelligence services. Were these services aware of the payments allegedly made by the multinational to terrorist organizations?

This sensitive issue - at a time when Western diplomacies, including the French, are reestablishing ties with a Syria now led by a former jihadist - will likely be at the heart of the defense strategy. In particular, that of Christian Herrault, the group’s former deputy COO. During the proceedings, he repeatedly claimed that the French authorities, through the ministry of Foreign Affairs, had “encouraged” Lafarge group to pursue its activities in Syria. These statements were confirmed by Solange Doumic, his lawyer, who believes this issue “is a key element of the case”.