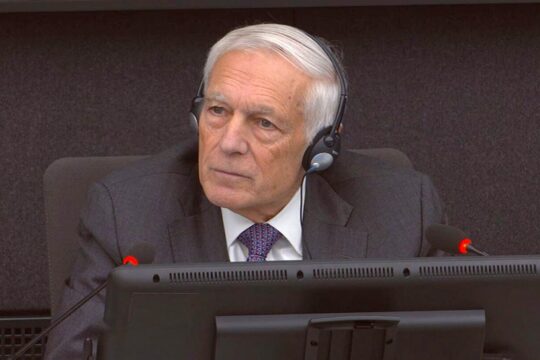

The presiding judge called the decision a “milestone” for the Hague-based Kosovo Specialist Chambers (KSC) last December when she announced a guilty verdict for Salih Mustafa on four counts of war crimes for running a detention facility in eastern Kosovo. Mustafa, who served as the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) commander of Llap Operation Zone in the north-east part of Kosovo during the 14-month struggle for independence in the late 1990s became the first defendant to be convicted of war crimes by the court. At 52, he was sentenced to 26 years in jail.

In April, the three-judge panel ordered Mustafa to pay 207,000 euros in reparations for the damage he caused to the victims who participated in the trial. Nearly all the detainees at the Zllash detention center were fellow ethnic Kosovo Albanians who were accused of collaborating with Serb forces. Detainees were held in a makeshift facility sometimes described as a cowshed, without adequate food, water, bedding, medical care or toilets, survivors said. They described being beaten, subjected to electric shocks and burned with candles, both by Mustafa and his men. “You were just waiting for death, when it will come. Today, tomorrow, you were waiting for you to be killed,” one witness, who testified anonymously, told the court.

No one’s responsible for payment

Eight victims participated in the trial, all anonymously. Their lawyer, Anni Pues, told the court that they are still experiencing the physical and psychological impact of their detention. “No amount of money can make good on the suffering they have experienced,” she told Justice Info. But, she adds, “the financial support is welcome.”

The amounts range from 2,000 to 80,000 euros, depending on the injuries sustained by the victim. The highest amount was awarded to victim V09/05, who was kicked, punched, beaten under he lost consciousness and burnt with a hot iron. He suffers from depression and PTSD, has difficulty sleeping and is afraid of anyone in a black uniform. The compensation took into account his suffering and how his experiences kept him from maintaining regular employment.

Mustafa himself has been declared indigent and there is no expectation from the victims that the money will come from him personally. The former KLA commander made his disdain for the court clear during the opening of his trial in 2021. Wearing a red and black tracksuit, the colors of the KLA, Mustafa told the judges: “I am not guilty of any of the counts brought here before me by this Gestapo office."

Unlike the International Criminal Court, the KSC has no trust fund for victims and the Kosovo government is not obliged to pay the reparations orders. “Victims should receive reasonable, appropriate, and prompt reparations,” the Mustafa reparations order states before calling on Kosovo to create a new funding mechanism. The legal framework of the court has no mandate for reparations, despite allowing for their order, and Pristina has little interest in amending it.

Pues says that she and her colleagues raised the issue of this gap from the outset.

Bekim Blakaj is the head of the Kosovo Humanitarian Law Centre. His organisation works to implement transitional justice in the region and described the reparations order as a “significant step forward in the realization of victims’ rights to compensation” in a press release. But the group is critical of the lack of planned implementation and called on the government to establish a mechanism for all of the war victims, not just Mustafa’s, to be compensated. “The court is not very popular in Kosovo,” Blakaj told Justice Info. It is seen by many as attacking the victims of the conflict – the Liberation army – rather than the Serbian oppressors. The war left 13,000 people dead, the majority of whom were Kosovo Albanians.

Anonymous witnesses

In 2015, Kosovo established the Committee for Crime Victims Compensation which offers victims restitution, paid from government coffers, when the perpetrators are unable to pay. The KSC judges noted that one avenue for payment could be this committee, though cautioned that the order against Mustafa exceeded the maximum compensation permitted by the fund.

There are other potential problems as well. The committee’s former head, Nesrin Lushta, told Balkan Investigative Reporting Network in 2022 that it wasn’t possible to pay for crimes that occurred before the program was established. Further, recipients cannot remain anonymous in the present system. Lack of anonymity is a major deterrent for any KLA victims, who are sometimes still seen as traitors. Every participating victim in Mustafa’s case was granted anonymity.

The court itself has had substantial issues with witness intimidation since it began. It operates under Kosovo law but is based in The Hague and is staffed by internationals in an effort to prevent interference. The court’s first convictions, in fact, were for precisely that. Two former leaders of the KLA War Veterans Organization, Hysni Gucati and Nasim Haradinaj, were found guilty of obstruction of justice, intimidation and unauthorized release of confidential information in May 2022. The pair were sentenced to four-and-a-half years in prison and fined 100 euros. The sentence was reduced on appeal to four years and three months of imprisonment.

Reparations aren’t sexy

Financing reparations and other transitional justice initiatives is a problem that has plagued post-conflict areas. “It’s not as sexy as criminal justice,” says Igor Cvetkovski, of the International Organization for Migration. He’s worked on reparations across the globe, from Germany to Colombia and is critical of the international community for often leaving restitution as an afterthought.

In speaking with Justice Info, Blakaj pointed out that the amounts awarded by the Kosovo Specialist Chambers were substantially higher than what had been given to victims in civil proceedings in Serbia and Kosovo or by the UN International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY). “This creates a huge discrimination among victims,” he says. Although by the economic standards of Kosovo, the amounts awarded are significant, Pues notes that her clients aren’t receiving exceptional amounts. “It is in line with what they would be entitled to had they received a war pension,” she says.

What injured KLA members receive for participation in the conflict was considered as part of the reparations assessment by the court. An expert report commissioned by the court to determine reparations, known as the Lerz Report, details the various benefits the veterans are entitled to.

Kosovo does have other reparations programs. Following years of lobbying efforts by activists, the government now offers a 230 euro monthly stipend to victims of sexual abuse during the conflict, a figure that is just less than the average salary. Human rights groups estimate there could be as many as 20,000 victims. Several senior Yugoslav Army officials were convicted at the ICTY for overseeing sexual assault as a form of persecution.

The KSC 207,000 euro amount isn’t settled either. The defense still has several more days to appeal the reparations order itself and the conviction is also being appealed. If an appeals panel reduces Mustafa’s liability in connection with the victims or concludes he wasn’t involved in some or all of the events, the reparations award could be reduced. In the meantime, the victims will wait.