Sciences Po Paris

المقال متوفر باللغة العربية / This article is also available in Arabic on the Syrian Justice and Accountability Centre (SJAC) website.

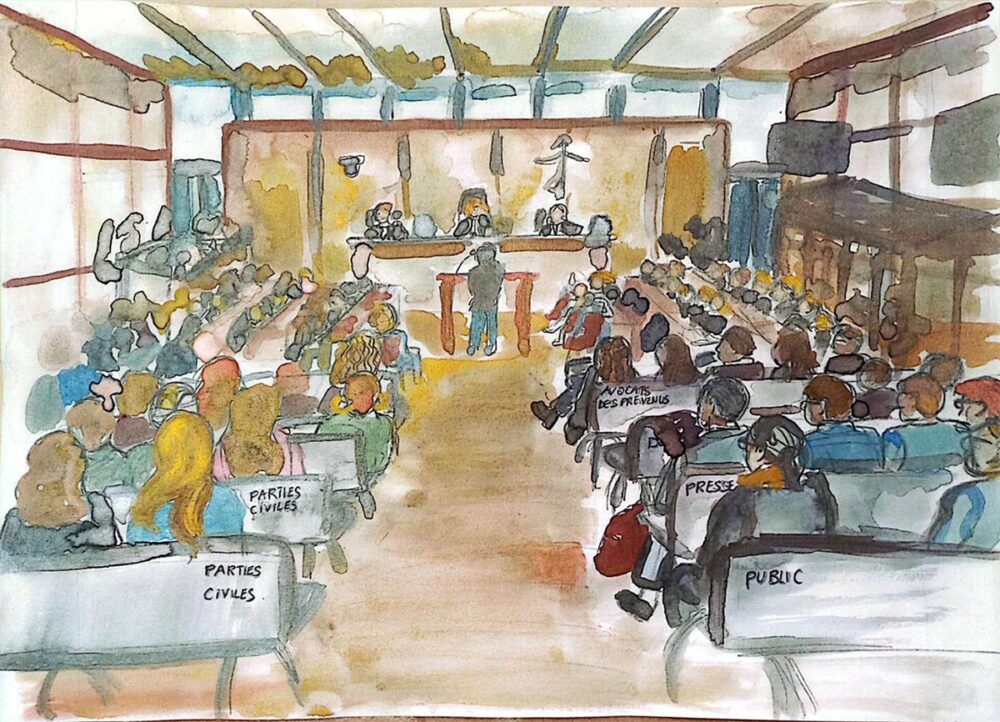

The second week of the Lafarge trial before the 16th Chamber of the Paris lower criminal court resumed on Tuesday, November 18, after a thirteen-day pause to correct errors in the indictment and deliberate on preliminary issues. The hallway, packed with reporters when the trial opened, was almost deserted.

This new phase of the trial was no longer about procedure. It was the first time we would hear the defendants speak, and their voices revealed a constant oscillation between two tones: on one side, the sharp, detached posture of corporate managers; on the other, a repeated insistence that they were “only” human and simply doing their job. Throughout the week, the presiding judge, Isabelle Prévost-Desprez, had to navigate these competing narratives, each pulling the courtroom in a different direction.

The defendants and their lawyers were scattered across the room, and two new faces stood out: Aman Al Jaoudi, a Jordanian citizen, and Amro Taleb, a Syrian, both absent during the first week. “You found your way to the tribunal… good, see what determination can do,” welcomed them the presiding judge, with her sharp humour. With that, the week in which every defendant would take the stand finally began.

Adjusting to corporate lexicon

After reading the indictment, the judge opened with an overview of the cement company Lafarge SA’s expansion, the broader Syrian context, and a detailed account of the terrorist attacks committed on French soil, walking the courtroom through decades of corporate growth and the grim chronology of jihadist violence. The moment carried particular weight: just five days earlier, Paris had marked the tenth anniversary of the 13-November attacks, carried out by the same terrorist groups the company is alleged to have financed months before while operating in Syria.

The unfolding events of this week’s trial bore little resemblance to the typical profile of terrorism cases; instead, the courtroom was filled with discussions of keels, coal deliveries, and production charts. We slipped into the world of industrial process, drifted into the language of industrial operations, a stark reminder of the central tension in this terror trial: the collision between the mathematical corporate logic of profit and the human harm that can be caused by those actions. The judge had to adjust to the language of corporate governance. She repeatedly noted that she was open to correction on corporate terminology and reminded the courtroom that she was not an economics specialist.

The first topic focused on “economic entities”, and the discussion was filled with technical vocabulary. The Common Terms Agreement with the European Investment Bank and the Lafarge Holcim merger were unpacked in detail. The defendants themselves spoke like executives, not accused individuals.

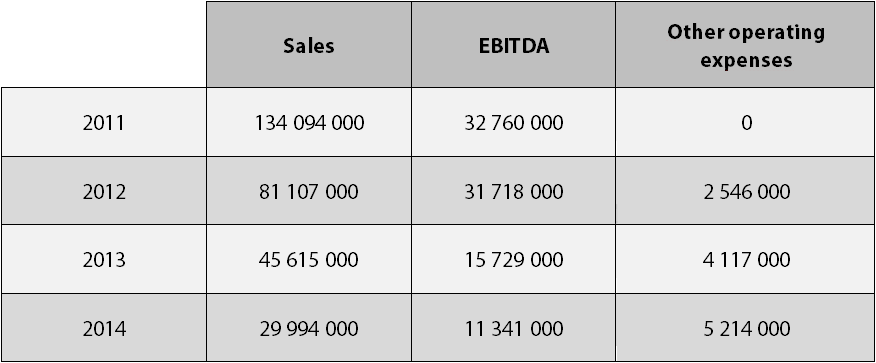

“At the time, Syria appeared promising,” former CEO Bruno Lafont said, referring to 2012 – a year into the civil war – as he justified the company’s investment exclusively in terms of profitability and opportunity, insisting on its “brilliant prospects” despite the war. For former deputy CEO Christian Herrault, Syria was not a “normal country,” but rather a difficult yet potentially lucrative terrain, more complex to manage than the “normal” national markets he was used to. These declarations were made when such tables were displayed on a large central screen above the judges’ heads:

The peculiar place of civil parties

This drift was reinforced by the defence teams. The courtroom is filled with specialists in corporate crime, tax fraud and white-collar high-profile lawyers. Lafarge SA is represented by Christophe Ingrain, known for money-laundering cases, and Denis Chemla, global co-head of white-collar investigations at Allen and Overy, a prominent law firm. The other defence lawyers, including Jean Reinhart, Jacqueline Laffont-Haïk and Mario-Pierre Stasi, come from the same world of droit des affaires, a point made clear when one of them, Solange Doumic, argued that, just like in tax evasion, the offence of financing terrorism has no direct victims and therefore leaves no legitimate place for civil parties, since they do not represent the “general interest.”

In 2021, just one day before the beginning of the trial for the 13 November 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris and St Denis, the French Supreme Court ruled that the victims’ association Life for Paris – one of the civil parties to the Bataclan trial – could not participate as a civil party in the related financing-of-terrorism proceedings, due to the lack of direct harm. Yet, this may not be so for the Syrian factory workers, who claim a direct link between Lafarge’s financing and the violence they suffered. In any case, because French criminal procedure allows civil-party applications until the end of the hearings, the presiding judge is permitting all civil parties to present their arguments, with a final decision on admissibility to come at the close of the trial. As a result, more than 200 civil parties – associations and individual victims in Syria and France – may still be heard and use the courtroom to describe the impact of Lafarge’s actions. They occupy a peculiar position, at once present yet not fully recognized.

Deflecting responsibility

Article 121-2 of the French Criminal Code defines that legal entities and natural persons are criminally responsible for offenses committed on their behalf by their organs or representatives. Similar criminal legal contract exists in at least 20 countries. The court focused in length on the operational chain between Lafarge SA and its Syrian subsidiary: who decided what, who reported to whom, and how decisions were actually made.

According to the indictment, Lafarge SA was operating while it exercised full control – through its holdings Sofimo and LCH – over the activities of its Syrian subsidiary LCS at the Jalabiya cement plant, and while it financed those activities through intragroup loans. During the investigation phase, both the Paris Court of Appeal and the Cour de cassation found that Lafarge Cement Syria S.A. (LCS) lacked any real autonomy, with effective integration of the subsidiary into the parent company that justified lifting the corporate veil.

The judge wanted clarity; the defendants offered blurred hierarchies and layers of delegation.Each defendant seemed to appear with a clear strategy: those close to Lafont emphasized distance from Syria; those involved in Syria emphasized the constraints imposed from above. This seemed to strangely reflect the typical systematic dilution of responsibility through the structural separation between decision-makers and implementers that we see with armed groups units. In such organizational settings, responsibility is continuously displaced: lower level defers to higher authorities, while those at the top deflect responsibility downward as being unable to control everything.

Two informal rivalries emerged: Lafarge SA and LCS Syria groups. Each was shielding itself without outright incriminating the other. The refrain “I don’t know” or “someone else would know better” became a shared defensive tactic – except when everyone could redirect blame toward those absent from the proceedings, such as businessman Hassan Firas Tlass. The judge even noted in irony to Lafont: “Since Firas is not in court, you can go ahead.”

Throughout the week, the hearings kept circling back to the Lafarge Group’s history and the leadership of Bruno Lafont, portrayed by former French Prime Minister Jean-Pierre Raffarin – called by defense as “témoin de moralité” (character witness) – as a model French industrialist.

The humanitarian in me

Between 2009 and 2012 Amro Taleb worked at LCS as a quality, safety, and environmental expert. He presented himself as a committed humanitarian after 2013, providing documents which demonstrated his unpaid volunteer work. He broke into tears in court, describing bombings he survived, children he tried to help, and his love for Syria. But the presiding judge confronted him with invoices from Greenway, his consulting company, showing he continued to be paid by LCS through 2014. Cornered, his narrative unraveled. “I was traumatized,” he said. “I pretended to know people. That was a lie… I was stupid, playing a dangerous game.”

Meanwhile, former director of the Syrian subsidiary Frédéric Jolibois offered the courtroom moments of levity, invoking his wife and children repeatedly, framing every career move as a joint domestic decision. He described choosing Jordan over South Africa because “expatriation is first and foremost a family adventure,” then drifted into a mini-lecture on Jordan’s history until the presiding judge cut him off. When pressed on whether he knew about the Syrian conflict and terrorist groups present in Syria, he insisted he did not; when asked whether his wife knew, he insisted she didn’t either. “So Mrs Jolibois does not read the newspaper?”, prodded judge Prévost-Deprez, prompting some amusement in the courtroom. His testimony painted the portrait of a man who appears to see the world through the lens of family life, even when that lens strains credibility.

Three defendants – former security managers Jacob Waerness and Ahmed Ibrahim Al Jaloudi, who had also worked for secret services, as well as Taleb – revealed connections to the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), a humanitarian organization supporting Syrian refugees. Each man leaned on this affiliation to present a more human, altruistic side. But the judge openly questioned the coincidence, sometimes with humor, sometimes with clear skepticism. Why did so many of the accused in a terror-financing case suddenly appear as humanitarians and why were they being paid by the NRC at the same time? It came to mind that humanitarian motives are a common defense also for French foreign fighters who went to Syria.

As part of the Capstone Course in International Law in Action, Professor Sharon Weill and eleven students at Sciences Po Paris, in partnership with Justice Info, are dedicated to weekly coverage of the Lafarge trial, conducting an ethnography of the proceedings. The members of this student group are Sofia Ackerman, Maria Araos Florez, Toscane Barraqué-Ciucci, Laïa Berthomieu, Emilia Ferrigno, Dominika Kapalova, Garret Lyne, Lou-Anne Magnin, Ines Peignien, Laura Alves Das Neves, and Lydia Jebakumar.