The two women must have looked emaciated, when Mahmoud A. allegedly stopped them at the checkpoint at the Northern end of Yarmouk in Damascus. It was a day in the year of 2014, and the total siege of the Palestinian neighbourhood in the Southern part of Syria’s capital city had been going on since July 2013. According to the indictment, Mahmoud A. started beating them up with a green plastic pipe.

The indictment states that “he hit them in straight downward movements,” and called them “vile”. It alleges that they fell to the ground, and, in a general outbreak of panic, were trampled by other civilians who had come to collect food parcels. “Even in this helpless position, he kept beating them.” In the eyes of the prosecution, these acts constitute the crime of starvation as a war crime: Mahmoud A. prevented the women from getting the food they desperately needed.

Mahmoud A. is one of five men accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity in Germany’s latest universal jurisdiction trial dealing with Syria. The Higher Regional Court of Koblenz, known for its landmark trial against two former Syrian intelligence officers in 2020-2022, has once again become the stage for prosecuting major crimes of the Assad regime and its allied militias.

Using the principle of universal jurisdiction, German authorities can prosecute grave international crimes committed in Syria, even when there is no direct link to Germany – and they have on numerous occasions over the past years. But this trial is different. It is the first to commence after the fall of the Bashar al-Assad regime in December 2024. And it is the first trial ever to indict starvation as a war crime – a step seen by some as a turning point in the prosecution of an especially cruel yet long neglected offence.

A pro-Assad Palestinian militia

More than ten years after the alleged crime took place, Mahmoud A. does not resemble the bulky tattooed militia man he was in 2014, according to some photos on the internet. He is handcuffed and pushed into the Koblenz courtroom in a wheelchair. In the public gallery, a woman jumps up and waves to him, only to be reprimanded by a security guard: communication with the defendants is prohibited. “I am just saying hello,” she says, smiling apologetically. “We haven’t seen each other for a whole year.” On this opening day on November 19th, friends and family of the defendants occupy more than half of the wooden benches in the courtroom. As Mahmoud A.’s four co-defendants shuffle in one by one with shackled hands and feet, their loved one’s sob, smile, wave, or gesture for them to stay calm.

The list of accusations against them is long. In 2012, Mahmoud A., Wael S., Sameer S., and Jihad A. allegedly joined the Palestinian militia “Free Palestine Movement” that cooperated with the Assad regime to quash anti-government protests in Yarmouk and enforce the siege of the neighbourhood from 2012 onwards. The fifth defendant, Mazhar J., is said to have been a secret service officer for the Palestine Branch, where “people who had mostly been arbitrarily arrested were tortured and held in life-threatening conditions, sometimes for several years.” A significant number of prisoners died, read the indictment, “as a result of torture and detention conditions.” Mazhar J. was allegedly responsible for the arrest and mistreatment of civilians in the secret service branches, as well as the violent oppression of the inhabitants of Yarmouk.

“You are playing with your life”

One of the main incidents described by the prosecutors is a demonstration that took place in Yarmouk after Friday prayers on July 13, 2012. The demonstration grew larger as it moved North on Palestine Street, where it was confronted by security forces, among them four of the defendants. “Unexpectedly, several people, including the defendants, opened fire deliberately on the demonstrators. Three people were killed as a result of these shots, among them Iyas Fahad, who was 21 at the time.”

At the mention of the victim, a tall man with curly hair and a tired face, started crying quietly. Accompanied by his lawyers, he sat on the left side of the courtroom facing the defendants. He is the father of Iyas Fahad, and has joined the proceedings as a plaintiff. According to the indictment, the defendants harassed him in the days after his son was killed. The regime wanted him to accept a death certificate with a fake cause of death, but he refused. “You are playing with your life,” they allegedly said to him. “Isn’t it enough that you lost one son? Do you want to lose another?”

In addition to this incident and the abuse of the two women at the checkpoint, further incidents are mentioned concerning one or several of the defendants: shooting at protesters, beating and arbitrarily arresting civilians at checkpoints, sending them to secret service branches where they later died. Samir S.’s defence lawyer read a lengthy motion demanding the court to drop the charges against his client as he had never owned a weapon or been part of any militia. The other defendants and their counsels have not commented on the accusations yet.

According to the indictment, Moafak Doua, the Syrian-Palestinian fighter convicted to life imprisonment in Berlin in February 2023, was also involved in several of the crimes. Another man, Mahmoud Sweidan, allegedly gave the orders in some of the cases. He later migrated to Sweden, where he was arrested last year at the same time as the Koblenz defendants, and is currently standing trial for suspected war crimes in Yarmouk.

Understanding Yarmouk

The situation in Yarmouk that led to Palestinian militias killing Palestinian civilians on behalf of Assad is not an easy one to understand. While the Palestinian Syrian community is often depicted as a homogenous group, there were in fact many different groups with different positions toward the revolution that changed over time. Their stances were shaped by various factors, among them the Assad regime’s longtime meddling with the Palestinian cause that divided Palestinian factions into those it supported and those it antagonized; as well as grievances with Palestinian militias that controlled the camps on behalf of the Assad regime.

At the outbreak of the Syrian revolution in 2011, Syria was home to around 560.000 Palestinians, one third of which lived in Yarmouk. Most of them came after the Nakba, the forced expulsion of Palestinians from their homeland during the foundation of the Israeli state, or after the Six-Day-War in 1967. Syria was one of the most hospitable countries at the time, treating Palestinians like citizens by giving them most of the same rights as Syrians. Refugee camps were not marginalized ghettos, but, like Yarmouk, became integral parts of the Syrian capital and key commercial centres.

Today, not much remains of the once vibrant neighbourhood of Yarmouk. As one of the most fought over areas in the Syrian war, the regime’s airstrikes have reduced the majority of its buildings to grey concrete skeletons or piles of rubble. At the beginning of the uprising in 2011, many Palestinian Syrians were cautious about getting involved. But Yarmouk quickly became a destination for displaced Syrians from other areas, taking in an estimated tens to hundreds of thousands of newcomers. It was also somewhat of a buffer zone between central Damascus and the southern suburbs where rebel groups were quickly gaining strength.

Yarmouk was often described by rebel leaders as the “lungs” through which they could breathe. The injured were treated there, families of fighters found shelter, and local youth sometimes helped with smuggling arms and ammunition. While local leaders were pressing for Yarmouk to remain neutral, new ranks of protesters soon formed in reaction to the regime’s repression in the camp and on its borders.

In July 2012, the Free Syrian Army (FSA), an anti-Assad armed group, attacked central Damascus from the southern suburbs bordering on Yarmouk, and just a few months later, regime airstrikes on Yarmouk began. The neighbourhood was quickly seized by the oppositional forces, which prompted the Assad regime and its loyal militias to launch what would become one of its first sieges – and its most brutal one. Over the following three years, hundreds died of hunger. Survivors shockingly described how people were forced to eat cats and dogs or killed by snipers while trying to forage for food.

Starvation as a war crime

It was against this backdrop that the indictment in Koblenz was presented. “While residents were initially able to leave or enter the district under strict reprisals, it was completely sealed off from July 2013 onwards.” The prosecutors said that the Syrian militias “Free Palestine Movement” and “PFLP-GC”, of which four defendants were allegedly members, participated in the siege. “It was no longer possible to buy food and medicine. By then, at the latest, the humanitarian situation was catastrophic.” While the Syrian regime allowed the UN agency for Palestinian refugees (UNRWA) to deliver humanitarian aid to Yarmouk at the beginning of 2014, residents were forced to collect the aid in the regime controlled North of Yarmouk, “where they risked being subjected to violence. Nevertheless, in order to escape starvation for themselves and their families, many people went there on the days of distribution.”

It is the first time ever that starvation is brought to trial as a stand-alone war crime – although it was charged for the first time in November 2024 in the arrest warrants by the International Criminal Court against Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former defence minister Yoav Gallant. “Starvation has long been perceived as more of a humanitarian problem than an international crime,” says Catriona Murdoch, Director of Legal Accountability and Advocacy at the Netherlands based human rights organisation Videre and a leading expert on starvation as a war crime. “It was seen as something that just happens during war – supplies run out; people are on the move – an inevitable consequence.”

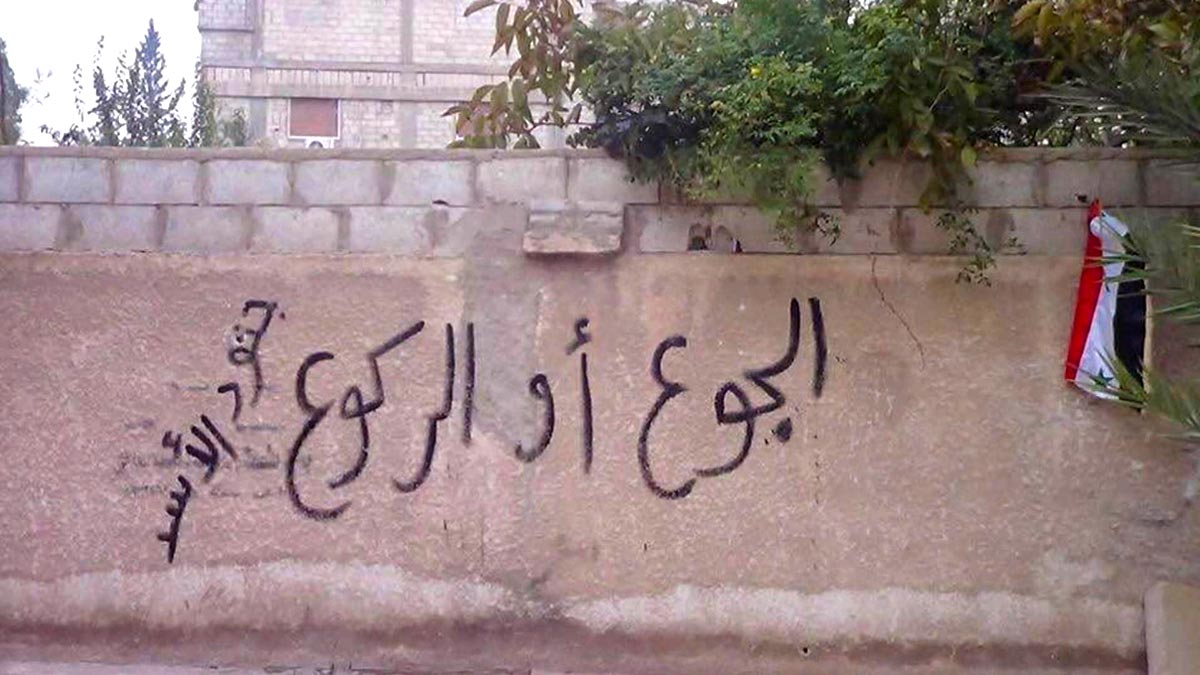

Murdoch has worked with Syrian NGOs on the siege of Yarmouk and has been in touch with the prosecutors working on the German case. For her, the sieges in Syria are emblematic of the deliberate criminal nature behind civilians going hungry. “The motto of the Syrian regime was: ‘Kneel or starve’, spray painted across the walls of many Syrian towns and cities."

Starvation is only a small part of the indictment in Koblenz and it refers only to one individual incident. But the trial could illustrate the broader patterns of siege and starvation in Syria, says Murdoch. She is hopeful that this first case will embolden other judicial authorities to take on the investigation of starvation as a weapon of war, for example with regards to Gaza or Sudan. According to Murdoch, Yarmouk is a clear-cut case and a good starting point to demonstrate the devastation caused by this crime. From psychological trauma to educational difficulties and stunting in children, to economical setbacks and lower birth rates: “It is a slow burn crime that impacts generations to come.”