JUSTICE INFO: How would you describe the situation for women and girls in Afghanistan now?

RICHARD BENNETT: Women are discriminated against, segregated, and their rights have been restricted to the degree that I and others have concluded that this is intentional, systematic, institutionalised. It’s an attempt to dominate one gender over another gender by a gender group in power. Therefore it reaches the threshold of gender persecution which is a crime against humanity. Further, if you applied to gender the language that defines apartheid in the Rome Statute, but only on the grounds of race, it appears to apply to the current situation in Afghanistan. There is evidence for that, not only in the actions of the Taliban but also in their policies, their decrees. Moreover, the Taliban enforce their ideology not only through decrees but by use of threats and violence. They don’t tolerate any dissent, and dissent often results in violent punishment. We have a lot of information about how women’s rights are restricted – they can’t wear what they want, they can’t go where they want, work where they want – but if we translate that into human rights language, the key violations are of women and girls’ right to education, freedom of movement, employment, and participation in public and political life.

You have called this a crime against humanity. Can you explain?

The yardstick I am using is the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC), and what I was talking about particularly was the crime of gender persecution, which is a crime against humanity in the Rome Statute. I reached this conclusion in a report to the Human Rights Council in June 2024. Then at the beginning of this year the Prosecutor of the ICC requested arrest warrants for the Taliban’s top leader as well as their chief ideologue who doubles as chief justice, and the Court’s pre-trial chamber issued those arrest warrants a few months later. These are for the precise crime that I had assessed a year or so before. So it’s more than my report saying so.

Now, some people may say that’s rather symbolic because they are not going to leave Afghanistan and they won’t be arrested inside Afghanistan. That’s probably true, but nevertheless, the warrants have been issued and they would be exercised if those people travelled into certain States, particularly States that are members of the Rome Statute.

You have also said you support the campaign to get gender apartheid recognized as an international crime, particularly in the context of Afghanistan. Why do you think that’s important?

First, we should not underestimate the crime of gender persecution. But for gender persecution there needs to be an identified victim and an identified perpetrator. It’s not a crime by a State but by individuals, whereas gender apartheid would also look at the actions, policies and laws of a State. Afghan women have said that in their understanding of apartheid, this best describes their own suffering. At the moment apartheid is only an international crime on the grounds of race, because it was developed in relation to South Africa, not on gender issues.

There are at least two ways of making gender apartheid an international crime. One is by amending the Rome Statute, and the other is by including it in a new treaty on crimes against humanity, which is currently being negotiated at the UN in New York. It would provide more obligations on other actors, particularly other States but also non-State actors including businesses, not to engage in ways that support a regime of apartheid. So it is a political as well as legal concept.

What is your reaction to the UN Human Rights Council’s decision at its last session to set up an Independent Investigative Mechanism on the most serious violations of human rights in Afghanistan, including against women and girls?

I supported it, because I think there has been a gap. But what this body will do has very little to do with gender apartheid, at least until it’s codified. It will investigate, collect evidence, including tracking perpetrators and linkage evidence, and create case files to facilitate criminal prosecutions. Its focus is on criminal prosecutions. There’s no other body doing that except the ICC. The difference is that the ICC can in fact prosecute. This body will be able to create the files but not prosecute itself, and would rely on the ICC or countries that exercise universal jurisdiction to undertake the prosecutions.

One important thing is that it is not looking only at the current situation. It has a comprehensive mandate. That means it’s not time-bound. It can go back into history and it can look at any party that has committed international crimes. So it is not targeted only on the Taliban. It can target the previous government, it can target other States, including NATO members and the US, if it wants to.

Do you know when it will be operational?

Nobody knows yet. There are a number of steps. The key one is the approval of its budget, and that takes place in New York probably around the end of this month. If its budget is approved, it will have a staggered start. The proposal in the budget that was approved by the Human Rights Council is that it gets up and running over a three-year period. It gets about a third of its staff the first year, and then a third and a third. So after three years it would have all its staff. But it can probably be operational with only some of its staff. We don’t know when that is going to happen, but it’s going to be a number of months away. After three years, it would have a total of 43 staff, according to the budget proposal.

You say “if its budget is approved”. Is there any doubt about that?

The Human Rights Council has supported a budget, but it needs approval of the UN General Assembly’s finance committee. The Human Rights Council resolution also calls for the establishment of a voluntary Trust Fund, so States and non-States can make contributions voluntarily, and I think it will need both regular budget and voluntary contributions.

Have many States expressed interest, or even made pledges?

There are no public pledges. I would only say that the European Union was the driver of it and member States of the EU have been taking the lead. We’ll have to wait and see whether the EU itself or its member States will make contributions. We really want the UN’s finance committee to approve the budget and for the member States who support it politically to also support it financially.

You have said that its mandate is not to do with gender apartheid, at least at the moment. But assuming it gets up and running, do you think it could contribute indirectly to the campaign for recognition of gender apartheid?

I guess it could. The strategy of this body is not within my purview. This would be up to whoever is appointed to lead the Investigative Mechanism to decide. As I said, I think it could help cases at the ICC. It could also help if there is litigation at the International Court of Justice (ICJ). As you may be aware, four countries have lodged a dispute with Afghanistan for violations of the CEDAW Convention [Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women], and such a dispute can potentially go to the ICJ. But I haven’t thought deeply about how it might help codification of gender apartheid, because that is on quite a different track, and codification is a political decision for the UN’s member states.

How will your work fit with that of the new Mechanism?

My mandate continues as before. There is not very much overlapbecause I don’t undertake criminal investigations. However, cooperation will be required in that when the new investigative Mechanism is operational, I am requested to transfer relevant information to it, provided I have the consent of the information providers. I will continue with my usual work of monitoring the human rights situation, making reports on it, recommendations for improvement, advocacy with all parties, providing support to civil society, and will continue to document human rights violations. But I document at a human rights standard, that is, I gather information at the standard of reasonable grounds to believe, whereas for a criminal investigation the standard is beyond reasonable doubt.

You talked about the Crimes against Humanity Convention which is under discussion in New York. What do you think are the chances that gender apartheid will be included in the Convention?

I think it’s a bit too soon to tell. In discussions last year, a number of countries – around ten – indicated that they would support inclusion, or at least consideration of inclusion. But there will be a new round of discussions in January, and submissions for the text are due by April. So I would say we would have a clearer idea by the middle of next year.

Are you involved in those discussions in any way?

They are discussions between States, although I have and will probably continue to make my views known.

But some NGOs are involved on the fringes…

They need to persuade States, they are the ones that decide. And yes, I am involved in that I am on record in reports and when I speak with States I advocate for it. You said NGOs are involved on the fringes, and that probably applies to me as well. By the time it gets to official discussions in New York, States have made up their minds, generally. So the work needs to be done in capitals, now. Because this is about apartheid, the States that are looked to for a signal are those that suffered apartheid – South Africa being the main one, also Namibia –, so a lot of countries are not making a commitment until they see which way South Africa goes, in my opinion.

Has South Africa not said clearly that it will support this?

No it hasn’t. It’s been a little unclear, as far as I am aware. Some time ago it appeared to support codification, and then it appeared to back away. It’s not clear what the South African position will end up being.

If gender apartheid is included in this new Convention, does that mean that international courts like the ICC will also have to recognize gender apartheid?

I can’t say how courts would deal with it, butit would strengthen international law. There is really a long way to go, because the earliest the treaty would be adopted is 2029, and then there would have to be a certain number of States that ratify this treaty before it comes into force. Until it reaches that threshold, it isn’t yet implemented. And then it’s unlikely to be retrospective, so it would only apply from the time it comes into force, which would be post-2029, at least. Codification would make a critical difference in Afghanistan and elsewhere, as it would greatly increase the pressure on any country that systematically institutionalises gender oppression. But there is no need to wait. We should already be standing in solidarity with Afghan women and calling on everyone to act against the gender persecution they are facing.

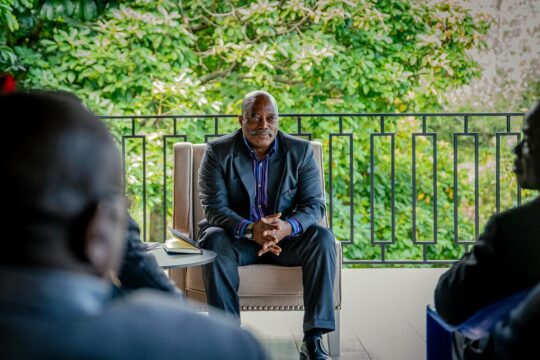

RICHARD BENNETT

Richard Bennett is a human rights expert from New Zealand. He has been the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Afghanistan since 2022. He has headed the human rights component of UN peacekeeping missions in Afghanistan (2003-2007 and 2018-2019), Sierra Leone, Timor-Leste, and South Sudan. He was also an advisor to the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission. Bennett worked for Amnesty International from 2014-17, first as its Asia-Pacific Programme Director and later as head of Amnesty’s UN office in New York. He is a visiting professor at the Raoul Wallenberg Institute in Lund, Sweden.