Time travelling back to 15 years ago is to reveal a different International Criminal Court (ICC), one where referrals from a relatively quiescent United Nations Security Council (UNSC) were not only possible, but where two came in quick succession. Both Darfur and Libya were grasped whole-heartedly by the first ICC prosecutor Luis Moreno Ocampo as ways to put his shiny new court onto the international map.

But whatever expectations were raised in 2011 by the Libya example – a swift referral, a swift application for arrest warrants from prosecution, and a swift approval from judges – those hopes of justice have never delivered accountability to Libyan victims. 15 years almost to the day after the uprising, “there has been absolutely no justice and accountability for the 2011 crimes,” says Jurgen Schurr of the NGO Lawyers for Justice in Libya. “From that perspective, Gaddafi’s death is yet another setback for victims seeking justice.”

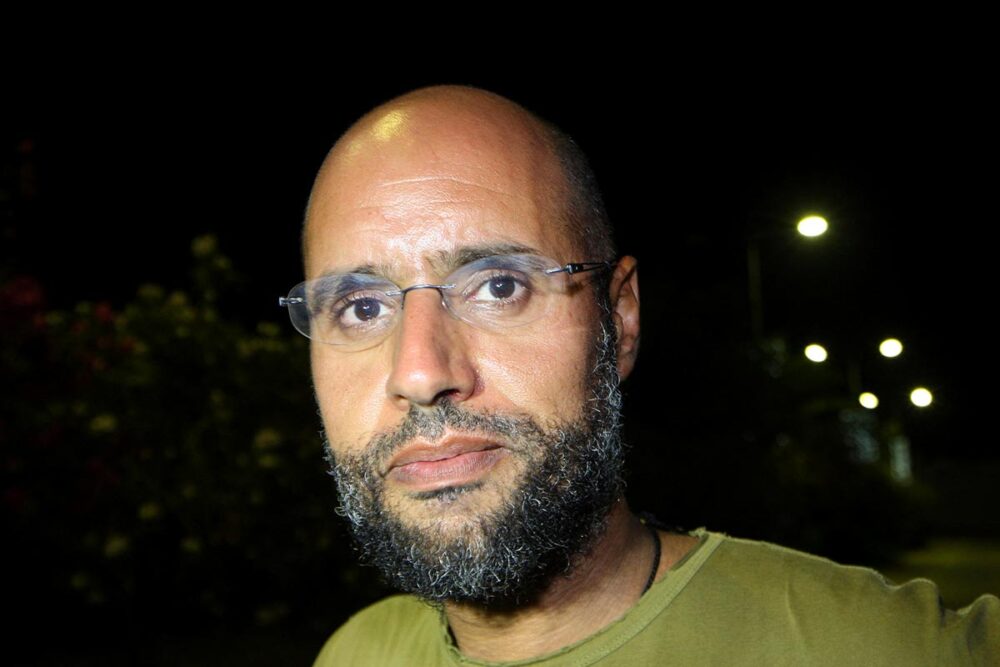

Ali Omar of the NGO Libya Crimes Watch says just the same. “Many victims hoped to see Saif al Islam stand trial, whether before a national court or the International Criminal Court, and to have his guilt or innocence determined through legal proceedings. It is important to stress that Saif al Islam was not the only person responsible for crimes committed in 2011. Dozens of other individuals implicated in serious violations from that period continue to enjoy impunity, both inside and outside Libya,” he adds.

Unprecedented speed

Libya was referred to the ICC while experiencing a violent civil uprising. NATO intervention began formally in March 2011 – authorised under the same UNSC resolution to protect civilians that involved the court. And just a few weeks after that referral, prosecutor Ocampo declared he was ready to ask judges for arrest warrants against three individuals, including Gaddafi the father, Gaddafi the son, and the head of the intelligence service – the triumvirate he declared most responsible for killings.

“It was unprecedented in terms of the speed,” notes Luigi Prosperi of Utrecht University. From the referral, adopted on February 26, 2011, to arrest warrants sought in March. That speed “led to a lot of criticism in terms of ‘what kind of material have you collected’, ‘what kind of analysis have you conducted on this material’, ‘did you rely on material provided for instance by NATO forces, the U.S. Secret services’? Because usually the ICC takes its time”. Never before nor since has the court moved so quickly.

The seven page arrest warrant against Gaddafi junior outlined “the use of lethal force” by security forces at the height of the Arab Spring movement which had swept across neighbouring Egypt and Tunisia “aimed at deterring and quelling, by any means,... the demonstrations of civilians against the regime”. It said that it was state policy, “at the highest level of the Libyan State machinery” to kill, injure, arrest, and imprison hundreds of civilians. “Saif Al-Islam Gaddafi, although not having an official position, is Muammar Gaddafi's unspoken successor and the most influential person within his inner circle and, as such, at all times relevant to the Prosecutor's Application, he exercised control over crucial parts of the State apparatus, including finances and logistics and had the powers of a de facto Prime Minister” and that “as part of Muammar Gaddafi's inner circle and in coordination with him, conceived and orchestrated a plan to deter and quell, by all means, the civilian demonstrations against Gaddafi's regime,” it read.

Looking back, the arrest warrant was “a very promising signal,” says Schurr, showing that justice was being taken seriously at the time and “making sure that accountability was part of the discussion” in the political transition.

The court’s show

But 15 years of twists and turns in the case is “indicative of just how long the ICC has been trying to achieve any degree of justice and accountability in Libya with very, very paltry results,” says Mark Kersten of the University of the Fraser Valley and the NGO Wayamo Foundation. It also illustrates the court’s impotence. Most notably, after Gaddafi was provided with an ICC defence lawyer, Melinda Taylor, she was herself detained, with colleagues, by a rebel faction holding him – an incident which required intense diplomatic manoeuvring to resolve. When finally back in The Hague Taylor said that the Libyan authorities themselves were to blame.

Libya was later represented at the court by renowned British barrister Philippe Sands – with Taylor glowering across the court without her client. Sands’ argument that Gaddafi should be left on home soil to be tried was ultimately rejected. Gaddafi's own defence was later led by Karim Khan, until he was elected prosecutor of the ICC in 2021. At no point, whatever the judges ordered, and no matter what changed in the Libyan political landscape, was Gaddafi ever transferred to the court’s detention facility in Scheveningen.

The crucial point, says Prosperi, is that after referring the situation, “the UN Security Council should then also have supported the ICC, by pressuring the authorities, to surrender an individual”. Like clockwork every six months the prosecutor (and now the deputy prosecutor) reports back to New York that there has been no progress in the Gaddafi arrest. The last time was in November 2025. At home for the last decade Gaddafi had been a free man. Released by rebels, rearrested by the authorities, tried in 2015 for a non-ICC offence and finally released through an amnesty in 2017.

Kersten believes the ICC did not push particularly hard to get him surrendered to the court. “I didn't hear conversations about how the ICC can't be forgotten during negotiations between the parties in Libya to hopefully avoid further bloodshed and unite the country. It fell under the radar. People were saying ‘okay he has this arrest warrant, but he's kind of detained and not detained. Maybe he's running for president and then there's just radio silence.’ All of this is to say, it's an open question as to how strong the case against him and others really was. Perhaps that's what explains the lack of urgency in the Hague to have someone like Saif al-Islam Gaddafi surrender to the courts,” he says.

Those most responsible or those easiest to get?

Meanwhile, NGOs like Lawyers for Justice in Libya have been pressing “continuously” for accountability for his role. “Gaddafi was one of the higher-ranking suspects wanted by the ICC since 2011. We intervened in relevant proceedings before the ICC as third parties, including to highlight that the best place to prosecute Gaddafi for alleged 2011 crimes was The Hague," says Schurr.

Also meanwhile, the focus of the ICC investigation has moved on from events in 2011. There are now several pillars, especially around crimes against migrants. Many more individuals have been investigated by the court. But the lack of arrests “demonstrate the limited ability of the ICC to exert effective pressure on Libya’s fragmented authorities to surrender suspects,” says Omar, while “equally importantly, authorities in both western and eastern Libya have shown a clear failure to cooperate in handing over individuals wanted by the Court, as some are themselves implicated in, or closely connected to, those sought by the ICC. Public statements and media appearances claiming cooperation have not translated into concrete action. Nearly ten individuals remain wanted by the ICC, some of whom continue to live freely,” he says.

At the moment, arrest warrants exist, publicly, against multiple mid to senior level officials, notes Schurr, “but not really those most responsible or those highest up in the chain of command. While different prosecutors follow different strategies in who they investigate, today we are at times wondering whether the OTP is charging those most responsible or those easiest to get”.

More recently the Libyan authorities agreed to ICC jurisdiction up to the end of 2027. “One would expect them to then follow up, and act upon this promise,” says Prosperi. “It's a bit of lip service I would say to international justice until we see some action”.

A naive pawn in the hands of powerful states

“We have serious concerns that the repeated killing or disappearance of individuals wanted by the ICC could turn into a pattern aimed at silencing cases and burying evidence through the physical elimination of suspects,” warns Omar. He points to the death of Mahmoud al-Werfalli, who was killed five years ago while wanted by the ICC, describing it as “highly instructive”. Because, “despite extensive and well documented evidence, including video recordings of crimes, there has been no clear move to transfer responsibility up the chain of command. This absence of accountability reinforces concerns that killings of suspects may be used as a means to evade justice,” he says.

If there are lessons learned from the long history of the ICC and Gaddafi, “the ICC has already learned them,” believes Prosperi. The most important, he says, is “not to transform a request for arrest warrants into – sorry if I am a bit brutal – moments for press conferences, for putting the ICC on the map, for standing in front of journalists and making the case for the ICC being effective”. He notes that recently judges changed the rules so that the prosecutor “cannot publicise or cannot make public the requests. It's not only about secrecy, but also about not pressuring the judges into adopting a decision that may be rushed because they are under a lot of political and more general pressure on the part of the general public. But it is also about being more effective in a way, because if we don't know about the request, or an arrest warrant issued under seal, then maybe there can be more negotiation behind closed doors that we are not aware of. They do not have to make public all of their work”.

Further referrals under the current permanent members of the UNSC are unlikely. Nevertheless, Kersten does think the Libya referral does illustrate what he’s called “the fatal attraction” between the court and the UNSC. “The dilemma is that if you don't accept Security Council referrals, there are contexts where mass atrocities are clearly happening that will remain outside of the jurisdiction of the court. Libya and Darfur are two of those examples where without the Security Council, there is no ICC action. But at the same time, it's poisoned, or in some instances, perhaps a little bit dramatically fatal, precisely because it ends up undermining the legitimacy and standing of the court, because it never comes with guarantees of cooperation. It pushes the court to undertake work – as it did in Libya – alongside controversial military interventions. Ultimately it looks like the ICC in these instances is used by states to either appear to be doing something supporting justice when in fact they're not, or to legitimise other types of activity, be it plunder or be it military interventions to get rid of people that the West doesn't like.”