“The appeal filed by the defence was partially satisfied," the Kyiv court of appeals said on July 29, adding that Russian soldier "Vadim Shishimarin is sentenced to 15 years of imprisonment". Shishimarin, who was 21 at the time, was found guilty in May of war crimes for killing an unarmed civilian and handed a life sentence, in the first verdict of its kind after Russia's invasion.

The sergeant from Siberia had admitted to killing a 62-year-old civilian, Oleksandr Shelipov. Shishimarin claimed he shot Shelipov under pressure from another soldier, as they tried to retreat and escape back into Russia in a stolen car on February 28. His lawyer, Viktor Ovsyannikov, had vowed to appeal the verdict, arguing that “societal pressure” weighed on the decision.

Lawyer with a machine gun

We arranged an interview with Ovsyannikov immediately after the session in which the Kyiv appeals court commuted the sentence. A few days later, we met at the lawyer's office in a multi-storey building in a central district of the capital.

Ovsyannikov, like most Ukrainians, recalls February 24 very well. "My wife got me out of bed at half past four... On the 25th I wrote an application asking to be mobilised. I was lucky to have enough small arms. They formed a unit of us and put us at checkpoints in Kyiv."

But soon, he had to return to his professional activities. In March, the SBU [Security Service of Ukraine, main intelligence agency of Ukraine] started identifying traitors, spies and looters. There were few lawyers in Kyiv at the time. Ovsyannikov started getting calls for cases where a defence counsel was needed at state expense.

Despite martial law, the obligation to have a lawyer remained. He accepted a power of attorney from the Legal Aid Centre and got back to work. "So, one day, I checked out from my checkpoint and left for the detention centre. I visited my client in uniform and said: ‘I'm a lawyer’. I still had a machine gun hanging on my shoulder," he recalls.

Russian servicemen captured and exchanged

Shishimarin was not the first Russian soldier he had to represent this spring. “There were Russian servicemen who were captured in the Kyiv region, charged for illegal border crossing, infringements on territorial integrity - non-violent acts. Promptly the cases were closed, because they were prisoners of war, and they were exchanged," the lawyer says.

In March, the courts in Kyiv were not working. The prosecutors took only precautionary measures, he says. They held a session in an office with a suspect, a lawyer, a prosecutor and a higher prosecutor, who listened to the parties and made a decision instead of a judge.

Shishimarin is not the first highly publicised case in Ovsyannikov's career. In 2018, the Obolonsky court in Kyiv was trying ex-president of Ukraine Viktor Yanukovych accused of treason in absentia. His five lawyers left the session in protest, so that the court asked the Free Legal Aid Center for a state-funded lawyer to protect the defendant’s rights.

It turned out to be Ovsyannikov. “The free legal aid, they never give the client's name first. They say you have an appointment for defence tomorrow at 9am. We'll send you the file and you'll see. When I saw it [on Yanukovych case] at night, my sleep vanished just like that. Maybe I wouldn't be so eager to take on Yanukovych's case... but this is the usual practice," he says.

He only took part for one day in court. "At first I had not planned to go to see Yanukovych. But he officially sent me an invitation", and the counsel considered it was his duty to meet the client, in the Russian Federation. “[The court] treated me like a piece of furniture... they said: here’s a lawyer, so we can have a hearing. The prosecutor brought himself a megaphone and some speakers system... In general, it was a very funny case,” he recalls.

“Addicted” to free legal aid

At the end of August, it will be 10 years since Ovsyannikov took the bar exam.

Since 2018, he has been practising as a public defender with the Free Legal Aid Centre. “Before that, I worked privately in economic, administrative and civil cases. On free legal aid, I’ve been working almost exclusively pro bono on criminal cases, and it quickly made me an addict... Private contracts make you run after the client, but here the client runs after you. Also, in our country, people don't have that much money for big lawyer fees. It’s a regular job.”

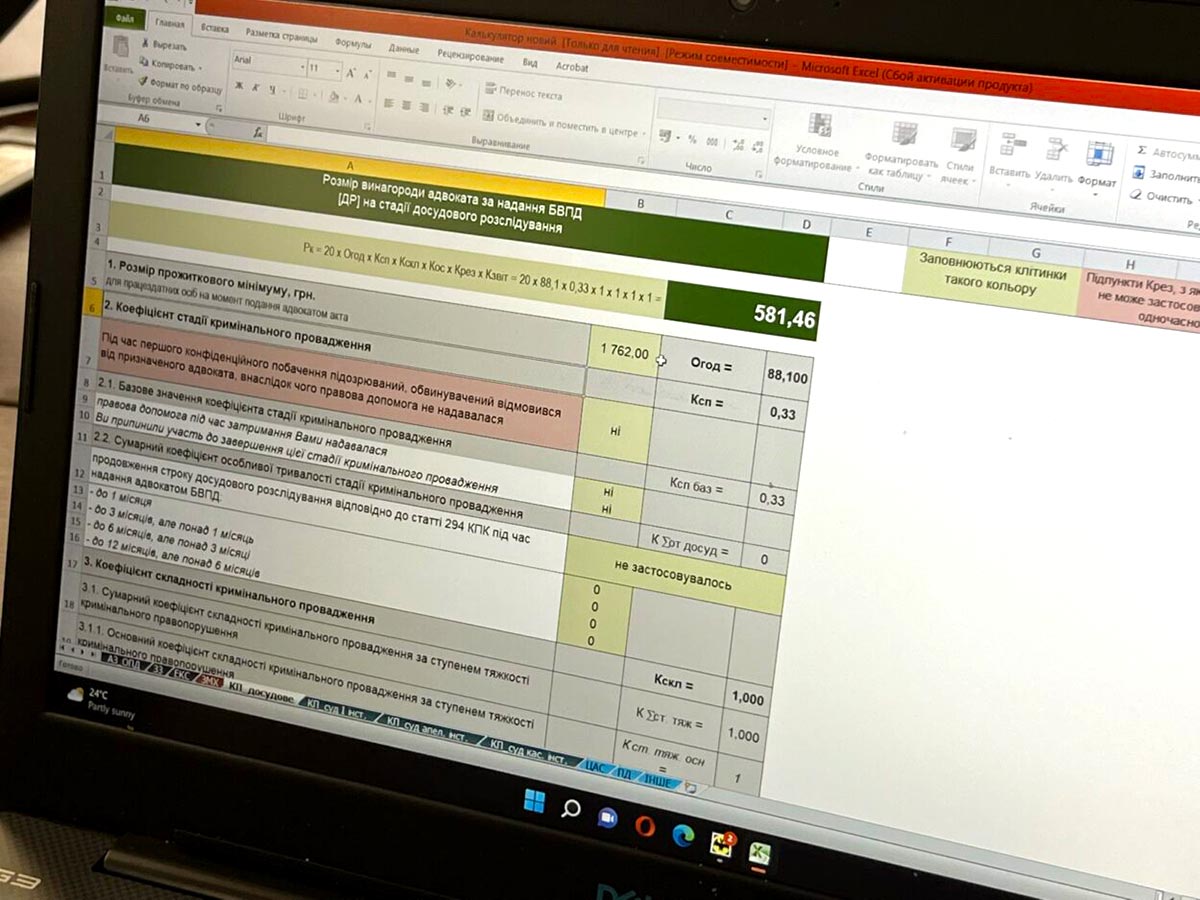

Ovsyannikov opens an Excel file on his laptop and shows how defence counsel's fees are calculated, depending on several parameters: detention, number of court sessions, severity of the crime, etc. In the case of Shishimarin, he says his fee was around 25 thousand hryvnias [675 euro]. This included the pre-trial investigation, first instance and appeal.

Currently, as a public defender, Ovsyannikov is also defending a deputy commander of a “Berkut” unit in Crimea, Serhiy Marchenko; an ex-chairman of the Yanukovych-era SBU, Oleksandr Yakymenko; a member of the “Ukrainian Choice” pro-Russian party, Ivan Komelov; and another Russian commander, Sergei Steiner. All in absentia. "I believe they can hire themselves a defence lawyer, but do they need one?" asks the lawyer. “Obviously, it is rather necessary for Ukraine, so that the verdicts are considered lawful.”

His office partner Andriy Domanskyy works also for pro bono legal aid. He is known as a lawyer for pro-Russian oligarch Viktor Medvedchuk, accused of high treason, as well as for Mikhail Romanov, a Russian serviceman on trial for murder and rape in the Kyiv region.

“My Mum will be drinking buckets of sedatives again”

Ovsyannikov entered the Shishimarin case on April 20, according to him. He received a call from the Legal Aid Centre after a hearing at the Solomenskyy district court in Kyiv. The law section they referred to - article 438 - indicates it is a special investigation.

“Who's the accuser? I asked. - ‘Security Service. Their office is on Shutova [street], it’s right in front of the court’. - Why not take the case, I thought, it's five minutes away. So I said yes. They gave me an order, with the investigator's contact details. I called. - ‘An interrogation is planned.’ - Who's interrogation, a witness? - ‘No, the detainee’. I am used to the fact that article 438 of the Criminal Code usually implies a special investigation, i.e. there are no detainees. If I'd known a person was in custody, maybe I wouldn't have taken the case. I still have certain moral prevention against it. But I have already said YES. To back out now, for one thing, would not have been very nice and polite. They know at the Centre that if I take an assignment, I go with it. And then curiosity won out. I was mentally preparing myself for the case. My Mum will be drinking buckets of sedatives again...”

“There was no way he would be acquitted”

Ovsyannikov continues his account. “The villagers recognised Shishimarin. When asked, he never denied. He told everything voluntarily. There was no influence on him. At least he didn't tell me about it. You all saw him. I had slightly different expectations. I thought he would be like John Rambo with machine gun tapes all around him. I was given the case file, I examined it. We went to the scene in the village of Chupakhivka. I talked with the witness, with the investigator. And I found the qualifications were too strict here,” he recalls.

He thinks Shishimarin should have been charged for homicide or simple murder. He noticed also a big gap: the testimonies from the other servicemen who were in the same car. One was killed, the two higher-ranking ones were exchanged. Only private Ivan Maltisov was left as a witness. There are no records of interviews with the exchanged soldiers. The lawyer suggests that law-enforcement agencies learned about the murder after the exchange.

After the first instance verdict, Ovsyannikov thought “the decision is too harsh”. “I believe my client is a victim of circumstances. If the situation were normal, he would not have done what he did,” he says. The lawyer believes that Shishimarin's actions, that tragically and accidentally led to the death of a civilian, are significantly different from the actions of those who deliberately fire at civilian objects, launch rockets and drop bombs.

In the appeal, Ovsyannikov initially requested Shishimarin to be fully acquitted. But the court explained that this was impossible from a procedural point of view. The appeal court cannot pronounce a new sentence, but only an ‘ordinary decision’ to close the case or to modify the term. And asking for the closure of the case would contradict Shishimarin’s position, who admitted guilt, confirmed the circumstances and agreed to be punished. Then the lawyer asked only to reduce the punishment from life imprisonment to 10 years.

“I understood that there was no way he would be acquitted. My colleagues joked that an acquittal could only be pronounced after the Ukrainian flag had been changed to the Russian flag. It was not advisable to drag out the case and send it back to the first instance court," Ovsyannikov said. At the same time, there was a lot of dirt on social media against him. He received phone calls appealing to his conscience, and threats. He says he did not take it seriously: "If a person wants to do something, they will not flaunt it, but simply do it.” In his opinion, the majority of citizens in Ukraine still understand the role of the bar and that everyone has the right to defence.

« To me Shishimarin is the same as other clients. Why does the society pay such attention to him? A scapegoat has been found. A person who accidentally shot our citizen in the first days of the war. Why is no attention paid to others? For instance to the pilot Alexander Krasnoyartsev... There was an investigation, then he was exchanged. These are cases where the persons were aware of what they were doing,” says Ovsyannikov.

This report is part of a series on war crimes, produced in partnership with Ukrainian journalists. A first version of this article was published on the Sudovyi Reporter website.

10 YEARS FOR A WAR CRIME IN CHERNIHIV

In another case, a Ukrainian court on August 8 sentenced a Russian tank operator to 10 years in prison for firing at a civilian building in the northern city of Chernihiv, at the start of Russia’s invasion. The Chernihiv court convicted him of a war crime.

The accused, Sergeant Mykhailo Kulikov “crossed Ukrainian border from Belarus” on February 24, the day the Russian invasion began, said the SBU, adding that he fired on villages as he proceeded to Chernihiv.

In court, Kulikov asked for forgiveness from the grandmother whom he scared when he hid in her chicken coop, apologized to the owner of the damaged apartment and “to the people of Ukraine”.