"What does it mean to fight against impunity? It means that we want to use this court to replace Kalashnikovs, rockets and shells with articles of the Treaty of Rome, so that from now on these articles will be our shells and rockets against people who have done harm to the people. If we have decisions three or four years later that no longer have any relation to the acts committed and do not seem to relieve the victims, that’s not good enough." So spoke Joseph Bindoumi, president of the Central African League for Human Rights, on May 23, 2015, during a debate on Radio Ndeke Luka, the main private radio station in the Central African Republic.

The creation of the Special Criminal Court (SCC) had just been voted amidst the enthusiasm of the Bangui National Forum, organized to promote peace and turn the page on years of chaos and violence perpetrated, in particular, by the so-called "anti-Balaka" militias and those of the Seleka, the rebel movement that overthrew President François Bozizé in March 2013 before being ousted a ten months later. But already some civil society actors, very active in the Bangui Forum and witness to the slowness of the International Criminal Court (ICC) since it opened Central African Republic investigations in 2007, were questioning the model of this new UN-backed "hybrid" court, composed of Central Africans and international staff.

Seven years and a few months later, the SCC handed down its first judgment on October 31, 2022, against three members of an armed group (Issa Sallet Adoum, Yaouba Ousman and Mahamat Tahir), who were found guilty of crimes against humanity and war crimes. They were convicted for events that occurred in 2019, years after the creation of the court, and caused the death of at least 32 civilians in villages in the northwest of the country not far from Paoua. The convicts are ex-rebels of the powerful "3R" group of Sidiki Abass, originally founded to protect the Peulh minority from anti-Balaka abuses. Their leader will not be tried. Appointed military adviser to the Prime Minister's Office after his participation in the peace agreement signed in February 2019 in Khartoum, Abass later joined in 2020 a new rebel coalition that tried to take the capital Bangui. Wounded in combat, his death was officially announced in early 2021.

Improving the quality of judgments

This first trial, which had been announced for April 19, 2022, got off to a false start itself, due to a boycott by defence lawyers dissatisfied with their remuneration. Having partially won their case (with a fixed fee that they still want to renegotiate), the trial was finally able to start on May 16. While Central Africans were able to follow the trial on local radio stations, it was not very visible internationally due to streaming difficulties. In private, legal experts close to the court confide that the trial chamber did not particularly shine during its debates or for the legal quality of its decisions. The lack of experience in international crime trials and the absence of assistants for judges and lawyers are among the reasons cited.

“At the SCC, the lawyer is alone, without an assistant," confirms Célestin Nzala, head of the special corps of lawyers appointed to act before the SCC. “In the trial, there were three defence lawyers, one for each defendant, and two lawyers for the civil parties. The second one for 51 civil parties arrived late. Donors were pressing for a trial. Things were rushed and they didn't manage to get enough of the civil parties together", he adds. Since then, legal advisors to the chambers have been recruited by the United Nations Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) and UNDP, two UN bodies that support the SCC, to "ensure quality decisions (including improving drafting of decisions) and "to ensure a fair trial (including bringing international lawyers to support national lawyers)", according to an external note to partners dated November 10.

This should serve two priority issues in particular: the appeal filed by the defence, and the civil parties' claim for reparations - for which a hearing is expected at the end of January.

Defendant apologies a “strong message”

Critics say this first trial in the form of a test was aimed mainly at obtaining renewal of the SCC's mandate, which expires in October 2023. "They rushed to organize a trial, to renew the mandate. They are there to drag it out. It's like all these UN projects, you can't expect much from them," says Maurice Dibert-Dollet, a former Bangui public prosecutor and advisor to the Court of Cassation. "In five years, a single case tried is nothing" with a yearly budget "equivalent to that of the entire Ministry of Justice, prisons, courts, everything included”, says another senior magistrate, a former Minister of Justice, who wishes to remain anonymous.

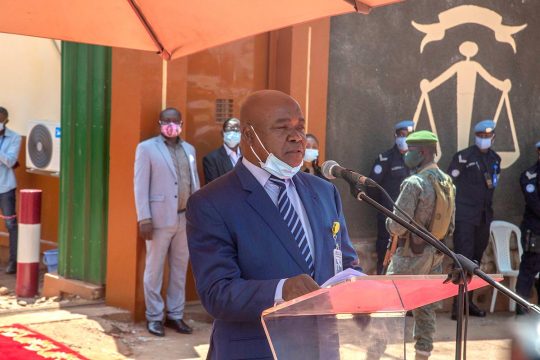

For others, this trial had the merit of existing and can give hope to victims. "This is the very first trial, there may be difficulties, but for me it went well. Victims are waiting for the Court to start judging those who committed the most serious crimes in the country. According to what we hear, the population are satisfied. Those who have killed have found themselves in court. Some have even apologized. It is a strong message, it is educational," said SCC president Michel Landry Luanga.

“The trial was edifying," he adds. “The defendants explained how they carried out their crimes. This is very significant compared with our [ICC] colleagues who tried Bemba [Jean-Pierre Bemba, Congolese politician and warlord, prosecuted for crimes committed in the Central African Republic in 2002-2003 and acquitted by the ICC in 2018] and failed. If they had gone for people against whom there is sufficient evidence, they would have had results. The population follows these trials where the perpetrators confess to the victims."

"We could have six trials" in two years

On December 28, the SCC had its mandate renewed for five years. After so many delays, the Court is ready this time to leave the starting block behind and get down to trials, according to the judges, investigators and prosecutors, providing figures to back this up. According to information communicated to Justice Info, the SCC has 15 defendants in custody as of December, plus the three convicted by the trial court. In addition to those imprisoned, three others are under court supervision, three are on provisional release, and one has "escaped”. Out of a total 19 cases under investigation, two could be close to completion, they say. And, according to prosecutor Muntazini, if each of the three investigating offices could bring two cases this year, "we could have six trials" in the next two years.