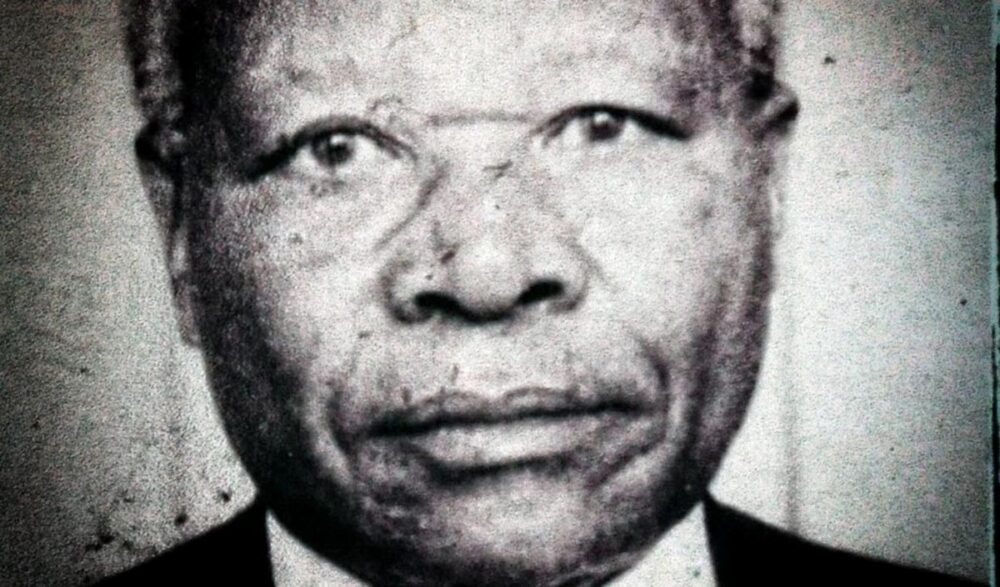

Félicien Kabuga, or more specifically, the spectre of Félicien Kabuga that the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) breathed life into, sustained, and then ultimately failed to try, is a Dickensian ghost of injustice past and present, and of justice yet to come for the post-Rwandan genocide international justice project. For the UN Office of the Prosecutor, Kabuga was their Moby Dick, their white whale who evaded them for 23 years. Having initially indicted Rwanda’s most infamous businessman on 6 counts of genocide and crimes against humanity in 1997, by 2011, with no arrest in sight, the prosecutor applied to hold “special deposition hearings”. The purpose of these hearings – which did take place although records of it seem inaccessible – was to “preserve the prosecution’s evidence against” Kabuga. In approving the prosecutor’s request, judges argued that Kabuga’s eventual arrest and trial would be important not only for victims, but “for the legacy of this tribunal and for reconciliation in Rwanda”.

Kabuga was finally arrested in March 2020. His trial opened in September 2022, and stopped in August 2023 when the appeals judges decided that the most important remaining suspect of the 1994 genocide, aged 88 or 90, was too mentally ill to understand the proceedings against him and defend himself fairly.

With Kabuga and his trial tied directly to the “legacy” of the tribunal as early as 2011, what reflections can be made after the fragmented, fraught, and curtailed process, and probably the final trial of the ICTR and the “Mechanism” that succeeded it? What can the Kabuga trial, and its unorthodox end, tell us about the anxiety of the post-Rwandan genocide international justice initiative.

The Ghost of Injustice Past and Present

Alison Des Forges, author of ‘Leave None to Tell the Story’ – a Human Rights Watch report which became something of a holy book to the Office of the Prosecutor – mentioned Kabuga in the ICTR’s very first trial. On 13 February 1997, in the trial of small-time teacher-turned-mayor Jean-Paul Akayesu, Des Forges introduced Kabuga as a founder of Radio Télévision Libre Des Milles Collines (RTLM) and a “close friend” of President Juvénal Habyarimana. The Akayesu trial and the ‘Media’ trial in 1997 and 2002 respectively, traced the outlines of the Kabuga-spectre that would come to haunt the tribunal. His two weapons of mass destruction? The radio, and machetes. Hate radio. Machetes. Two images which have become almost synonymous with discussions of the genocide in Rwanda. Both attributable to Kabuga, according to oblique references to his role as a kind of all-powerful facilitator of hatred and violence. When Rashid S. Rashid stood to open the prosecution’s case on 29 September 2022, he announced that Kabuga “did not need to wield a rifle or machete at a roadblock”. Nor did he need to “pick up a microphone to call for the extermination of Tutsi”. Kabuga – off stage both during the genocide and the ICTR’s justice crusade of the late 1990s and 2000s – was being narrated as a kind of spectral supervillain, finally being brought into the arena for a moment of reckoning.

The trial sessions – limited to 2 hours per day, 3 days per week, on account of Kabuga’s poor health – stuttered along with a kind of confusing urgency. Presiding judge Iain Bonomy would intensely and insistently tell witnesses to “answer the question asked”, and to answer “as precisely as possible”. But the evidence the witnesses were there to provide was often so indirect, so convoluted, and so inferential, that such directness was almost impossible. There were different layers of tension in the trial: between the nature of evidence available and the nature of the evidence desired and needed to prove the crimes charged; between the tribunal’s and witnesses’ manners of narrating the evidence; between the stunted, slowed trial sessions and the palpable urgency in the courtroom; between the alleged mastermind behind the Interahamwe militia and RTLM, and the distant figure whom witnesses could rarely place in the thick of things.

Amidst all this, the ghost of Kabuga’s past-self remained as ephemeral as he had allegedly been during the genocide, and as he had been during his years out of reach of the long, scrambling arm of international law. The format and timing of the trial conflicted with the nature of the charges, rendering counsel and witnesses alike unable to fill out the lines of Kabuga’s role in the genocide, unable to rein in this spectral injustice. In February 2022, the prosecution announced its intention to present the evidence of Alison Des Forges, the tribunal’s first narrator of Kabuga. Des Forges, a giant of the academic community on Rwandan history and the genocide, was killed in a plane crash near her home in Buffalo, New York, in 2009. Her evidence was yet to be heard when the trial reached its premature conclusion. The question of how a trial chamber would interpret the evidence of a deceased expert witness is one more question which now remains unanswered.

In the wake of the curtailed trial of Slobodan Milosevic, former President of Serbia who died in his cell in The Hague while on trial for crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide, scholars scrambled to address the question of whether any meaningful narrative could be gleaned from the process. But a trial without a judgement is not a trial without a narrative. Narratives are the very lifeblood of the international criminal trial, as the prosecution’s delicately constructed case theory is challenged by the defence, and its evidentiary foundations tested. Kabuga’s aborted trial – conducted largely in private session, with very little direct examination of witnesses – is a cautionary tale about the dangers of claiming that the narrative of any one individual, told through the prism of the criminal trial, can hold the key to justice for survivors and victims, the legacy of the tribunal, and reconciliation for the country of Rwanda. International criminal tribunals, again and again, build a kind of jurisprudence of expectation, which is almost impossible to match, let alone overcome, through the narrative of a single individual within a single trial. This is increasingly true in recent years as more and more of the modern trial’s narrative is hidden from the general public, and from victim and survivor groups, due to prolonged, almost systemic private sessions. The available narratives expressed in the Kabuga trial, after 23 witnesses, came nowhere close to reflecting the implied frenzied agency of the man who had facilitated the two most powerful drivers of the genocide in Rwanda: the call to violence and the mode of violence.

Whose interests are “justice interests”?

Two crucial decisions were made by the trial chamber and appeals chamber in June and August respectively. First, the trial chamber ruled Kabuga unfit to stand trial, but promoted a legally unprecedented and untested form of ‘trial without conviction’ – an “examination of the facts” – instead. In August, the appeals chamber quashed this attempt to continue the proceedings. With these two decisions, the tribunal has had to face the reality that the ephemeral Kabuga will remain just that. But the striving of the trial chamber to prevent the termination of some kind of examination of Kabuga also sheds light on the anxieties of a justice-project fearful of being rendered irrelevant. An aging tribunal, confronting an aging accused, seemed haunted by the ghost of justice yet to come.

There is, perhaps, a point in any trial at which the spectre and spectacle of justice overtakes the actors tasked with performing, enacting, and achieving it. In the 2011 decision to grant special deposition hearings, the judges found it to be “in the interests of justice” to grant the prosecution’s request. The initial decision, of June 2023, to hold an examination of the facts, was also in line with prosecution submissions that it would be “in the interests of justice” to do so. In his dissenting opinion, Judge Mustapha El Baaj considered it to be “in the interests of justice” to continue with the trial, making accommodations for Kabuga’s continued participation. Prosecutor of the Mechanism Serge Brammertz, expressing his disappointment at the Appeals Chamber’s decision, noted that victims had “put their faith in the justice process”. He reassured them that “it is not the end of the justice process”.

The concept of the “interests of justice” is, of course, not an invention of the Kabuga trial. It is enshrined in the statute of the Rwanda Tribunal, and indeed in the Rome Statute, which underpins the International Criminal Court. But the repetitive invocations of “justice” to try and keep hold of an imagined Kabuga, gradually slipping out of the court’s hands, begs the question of whether the Kabuga on trial in The Hague in 2022-23 was ever the Kabuga the court wanted him to be. Are the “interests of justice” ever truly separable from the instrument of justice which claims to represent those interests?

A sobering moment

The challenges of trying an aging accused were magnified by the contradictions of trying a figure who had been built into a mastermind of the genocide by trials which were not designed to investigate his guilt or innocence. It is possible that even for the juggernaut of the tribunal, the “interests of justice” in such a case would be impossible to fulfil. It appears that this has indeed been the case in the trial of Félicien Kabuga. One error of the tribunal was perhaps to attempt to put its own face on this particular justice process, and, crucially, to hold the trial it wishes it had held in 1997, or at least in 2011. While the decisions of the trial and appeals chambers, and the statement of the prosecutor, place the blame squarely at the feet of Kabuga and his prolonged flight from the law, perhaps it is time for international tribunals to examine the narratives they tell themselves about the atrocities, societies, and individuals they judge, and reckon with the limitations of their role in doing so.

Just outside of Arusha, Tanzania, there sits a UN-constructed city on a hill: the ICTR’s Mechanism complex, opened in 2012. The complex houses an extensive library, covering every aspect of international criminal law and the genocide in Rwanda, and a state-of-the-art research room, with digital access to all available judicial records, and space to consult the paper archive. When I visited these rooms in June 2023, (including by chance the day the trial chamber’s decision on an examination of the facts was released), every clock was either stopped, or incorrect. It seemed apt for an historical tribunal which is still grappling with, and racing against, time.

PhD Researcher at University of Amsterdam and NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust, and Genocide Studies, examining the construction of historical narratives within international criminal trials.