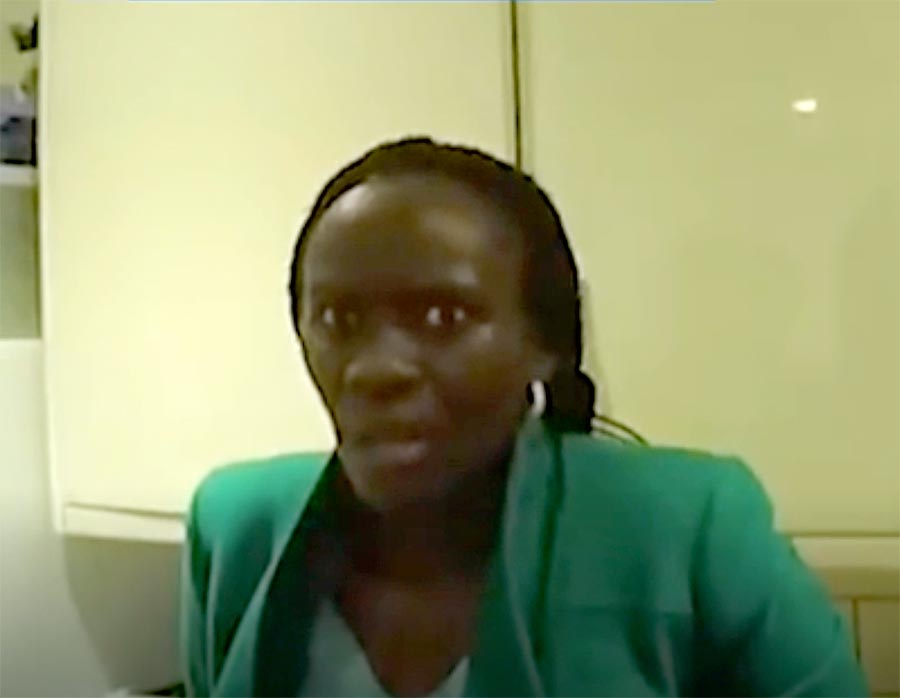

The footage is grainy, and the sound quality muffled, and yet UN and Ugandan Judge Lydia Mugambe’s sharp gasp is audible, as her eyes widen. She has just been told by a British police officer – whose bodycam footage gives us the view of the scene – “Unfortunately, I am now going to have to arrest you” under the UK’s Modern Slavery Act 2015.

The arrest took place in Mugambe’s home, in a village just a 20 minute drive from where she was pursuing her PhD in law – with a focus on human rights – at Pembroke College Oxford. In February 2023, police had received information indicating that a woman was being held as a slave at this address. In a trial at Oxford Crown Court in February and March 2025, the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) detailed how Mugambe had worked alongside Uganda’s then-Deputy High Commissioner to the UK, John Leonard Mugerwa, and how the two had arranged to bring a young woman from Uganda to the UK on a visa that stated she would be working for Mugerwa’s office. Instead, Mugambe picked the woman up at the airport and drove her to her home, confiscated her passport and phone, and forced her to perform domestic labour.

“She said she would burn my passport”

When the woman reached out to a friend who contacted UK police, evidence then showed that Mugambe tried to persuade the woman not to testify. The victim – who, under the UK’s Modern Slavery Act, has been granted lifelong anonymity – told the court: “My existence to Lydia was not important… Even after the police had visited her house on first occasion, Lydia told me she had the authority and that she would burn my passport and bank card. She also said she would call the police because I was in the UK illegally”.

A jury found Mugambe guilty of four counts: conspiring to break UK immigration law, requiring a person to perform forced or compulsory labour, conspiracy to intimidate a witness, and facilitating travel of another person with a view to exploitation. On 2 May 2025, Justice Sir David Foxton handed Mugambe a prison sentence of six years and four months, in what he said was a “very sad case”. The first three years of the sentence are to be served in prison, with the second half “on license, in the community”. She was also handed a lifelong restraining order against the victim, and ordered to pay £12,160 [14,440 €] in compensation.

A more political affair than it seems

The extraordinary case, which seemed to unfold rather quietly at first, finally ended this month with expressions of shock and indignation from various observers, practitioners, and researchers on international criminal law. But the events themselves reveal much deeper questions and issues of power, privilege, and politics.

In the rush to note the irony of an international judge and PhD student in international law and human rights being convicted of such serious crime, there’s another aspect of Mugambe’s case that has been slightly obscured: the political.

First is the issue of her co-conspirator, John Leonard Mugerwa. Mugerwa knew, according to prosecutors, that the victim would “work in servitude for Mugambe”. According to media reports, Mugerwa and Mugambe struck a deal whereby he would support the victim’s fraudulent visa application in exchange for Mugambe trying to influence a judge back in Uganda, where Mugerwa was facing legal action. Justice Foxton noted that the Ugandan judge in question, “to her credit”, had refused to take Mugambe’s calls.

According to his LinkedIn, Mugerwa moved back to Kampala, Uganda, in September 2024, where he is currently serving in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The prosecution had authorised a charge against Mugerwa similar to Mugambe’s, but was unable to proceed due to his diplomatic immunity, which (unlike the UN’s response to Mugambe’s charges) the Ugandan government did not waive.

It is possible that Mugambe herself may not remain in a UK prison, even for as long as half of her sentence. Uganda’s Monitor reported as early as October 2024 that the Ugandan government had “plans to save judge on trial in the UK”. In April 2025 Uganda signed agreements with several governments – including the UK – which allows for Ugandans serving prison sentences abroad to serve the remainder of their sentences “at home”. Protesters outside Oxford Crown Court in May held up signs defending Mugambe and decrying the case as one of cultural differences, and political exploitation. One sign asked the question ‘Who is Exploiting Who in this Case?’.

While it was not clear (to me) what the insinuation of that slogan was, it does speak to a sense of perceived political manoeuvring apparently felt both by those defending Mugambe, and those at the prosecution office trying to unpack her conspiracy with Mugerwa. The March 2025 bodycam footage in which Mugambe indignantly asserted diplomatic immunity – “I am a judge in my country. I even have immunity” – smacked of privileged entitlement, at the time. While those words were not, strictly speaking, true, there is no doubt that the case is more political and politicised than it first appeared.

Power and (International) Law

Mugambe worked at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) in the early 2000s and early 2010s, first in the ‘Chambers Legal Support’ section, and then in the Office of the Prosecutor. In 2013, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni appointed her to Uganda’s High Court. She served there until 2020, when she began working towards a PhD in Law, at the University of Oxford. Alongside her PhD, she was appointed as a Judge at the ICTR’s successor, the United Nations International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Trials (UN IRMCT).

Her profile on the IRMCT website – removed only recently, listed her initial appointment as 26 May 2023, and her “current term” as stretching from 1 July 2024 until 30 June 2026. She was listed as having been involved in “a number of matters” as a single judge. A scouring of available documentation on the Mechanism’s digital database reveals just one mention of Mugambe. In November 2023, President of the Mechanism, Judge Graciela Gatti Santana, denied the Stanislav Galić’s application for early release. Galić – former commander in the Bosnian Serb Army – was convicted of crimes against humanity and war crimes at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) for his role in the campaign of sniping and shelling attacks on the civilian population of Sarajevo, between 1992 and 1994. In 2006, an Appeals Chamber altered Galić’s 20-year sentence to one of life imprisonment. In September 2023 Galić applied for early release (he also did so in 2021, and again in 2024). Judge Gatti Santana noted, in her decision to deny his release, that she consulted with Judge Alphons Orie, who had been a judge on the bench which sentenced Galić. “As no other judges who imposed the sentence upon Galić are Judges of the Mechanism”, she also consulted one “Judge Lydia Mugambe”, who agreed with Orie that Galić was ineligible for early release.

UN Mechanism opaque statement

As someone who observes a lot of international criminal trials – through the archive, video-link, or in person – I am always keen to remind people that judges are human, and not the consistently removed, objective, and rational automatons a trial’s audience often insists that they be. Usually, when I make the point about ‘flawed’ judges, I am referring to instances where they get angry, emotional, or even on occasion fall asleep during a boring trial hearing.

When a serving Mechanism Judge was convicted of ‘modern slavery’, however, I expected quite a swift, severe, and public reaction from an institution steeped in the language of justice for victims of serious crimes. On all three counts, my expectations were disappointed. First, Mugambe’s profile remained on the Mechanism’s website until 3 days after her sentencing – two months after her conviction. Second, the removal of the profile coincided with an opaque statement, noting that the Mechanism had waived the immunity Mugambe would have been entitled to as a UN Judge, but saying very little else. Third, the statement vaguely noted that since the Mechanism had become aware (in July 2024) of the investigation into Mugambe, it had “taken all appropriate administrative actions”, including “discontinuing Judge Mugambe’s participation” in Mechanism business. Mention was made only of “certain charges” against her: nothing about the nature of the crimes for which she was convicted.

As someone who had followed Mugambe’s case for months at this point, I found this reaction frustrating. But it also raises some important questions. What duty does an institution like the IRMCT have when dealing not with crimes committed by individuals it pursues, arrests, and tries, but by its own staff? Suspending Mugambe’s participation is only one step, surely, to “protect the integrity” of the institution. The statement ends with a note that further comment is impossible due to “the confidential nature of internal procedures”. But this confidentiality, combined with the slow response, gave observers an impression of inaction at best, and apathy at worst, in response to Mugambe’s crimes.

‘Integrity’ goes, surely, beyond the procedural? As the International Criminal Court’s prosecutor Karim Khan faces a new onslaught of allegations that he is avoiding his own reckoning by “Hiding Behind Atrocities”, other justice mechanisms must surely reckon with the more political, public-facing aspects of the ‘integrity’ of their work. In the case of Mugambe, a better balance between confidentiality, condemnation, and clarity seems to be in order. Two days after the first statement, a second followed, when Mugambe officially “resigned” as a UN Judge. Though almost identical, it contained a paragraph which read as follows: “The charging and conviction of a United Nations judge for crimes of modern slavery, immigration violations, and witness intimidation are extremely grave matters. The Mechanism has and remains committed to facilitating the proper, fair, and efficient administration of justice.”

How should international justice mechanisms proceed when the cries of injustice are coming from inside the house? It is, unfortunately, an all too topical question. The story of Judge Mugambe can (hopefully) show other institutions that the answer is not to plead confidentiality and fall silent. Procedural and public ‘integrity’ must form a balancing act.

Lucy J. Gaynor is PhD Researcher at University of Amsterdam and NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust, and Genocide Studies, examining the construction of historical narratives within international criminal trials.