When is a trial no longer a trial?

As of 25 September 2025, it was 1092 days since the trial of Félicien Kabuga opened on the premises of the International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals (IRMCT) in The Hague. That day, Thursday 29 September 2022, I walked into Courtroom 1 – in the building which now houses the IRMCT but was previously the home of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) – amidst a swarm of journalists, legal interns, diplomats, and other members of the public. I was three weeks into a PhD about historical narratives and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR). Now, three years later, I have almost finished that PhD. Many of the interns may by now be well on their way to careers in their own right. Some of those same journalists who were there in 2022 now write about warrants for senior leaders of Russia, Israel, and Afghanistan. They cover what many consider to be the imminent collapse of the International Criminal Court (ICC) under both sanctions from the government of the United States of America, and the weight of its own contradictions and challenges. Others consider, even, the potential death of international law itself. And still, Félicien Kabuga sits where he sat over 1000 days ago: in the United Nations Detention Unit, about a 10-minute drive (or bike ride) from the courtroom.

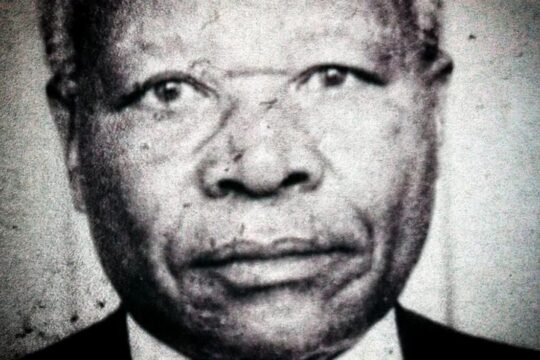

His trial ended three times: first in March 2023, when a team of three medical experts ruled that he was unfit, by way of dementia; second in June 2023, when a team of three judges ruled that his trial proper would end, but continue by way of an “examination of the facts”; third in August 2023, when a team of five different judges threw out this suggestion as impossible, and imposed an ‘indefinite suspension’ on the trial of one of the alleged kingpins of the genocide in Rwanda in 1994.

And still, Kabuga remains.

I don’t know why I chose to attend this particular status conference in person. The 780 days since the Appeals Chamber declared an indefinite suspension have been punctuated by such conferences. During these sessions, everybody in the courtroom invariably expresses frustration that Kabuga is still where he is. Then there is a pause [at least from the perspective of the public], until we reconvene to hear the same frustration, and Kabuga sits – still – where he is. Perhaps, having attended the hearing in absentia of LRA leader Joseph Kony at the ICC just two weeks before, I had not yet had my fill of unorthodox international legal procedures. Perhaps it was the imminent end of my own PhD, bookended as it was by Kabuga’s legal odyssey, that made me nostalgic. Either way, I walked once more through the security scanner and was handed my individually printed paper ‘Visitor’ ticket: no laminated electronic passes like those at the ICC, the IRMCT’s more glamorous, headline-hogging sibling down the street.

Strolling around the lobby of the Mechanism in 2025 feels like entering a time capsule. There are paper posters with QR codes (though you are not allowed a phone) advertising online exhibitions of the ICTY and ICTR archives, and ‘Children in Conflict’. There are framed children’s drawings made during an ICTY outreach workshop at the 2014 Sarajevo Kids Festival. In the far corner hangs a dramatic sign: ‘Bringing war criminal to justice and justice to…”. The word “victims” is hidden behind a defunct computer monitor. In the grand atrium, where trial observers go through another security scanner, past photos of IRMCT and ICTY judges, and up some polished marble stairs to Courtroom 1, there is another hanging banner. It reads ‘Nuremberg 1945’ at the top, and ‘The Hague 1993’ at the bottom. Each label is accompanied by a picture of the respective courtrooms. A red banner across the middle reads: ‘The First International War Crimes Tribunal since Nuremberg and Tokyo’. It was quite difficult to make out the details in the pictures, as the lights in the grand atrium were turned off. A broken sound board in the corner carried several stickers labelled ‘Not woking’.

If the Mechanism’s premises, and Courtroom 1 in particular, seem worn-down compared to the glossy IKEA-showroom of the ICC, it’s because they are. Both have, quite literally, borne the weight of justice, and violence, at a volume much greater than the newer, permanent court. The IRMCT’s home might be a premises that seems dusty, or out of date. But it has a history. Since 1993 it has seen some of the most notorious names from the violence and genocide in the former Yugoslavia occupying its chairs, including former Serbian President Slobodan Milošević, and convicted genocidaires of Srebrenica including Ratko Mladić and Radislav Krstić. The room has also seen a rotating case of legal actors, many of whom have continued working at the forefront of international criminal justice. That includes the man who, on 25 September, cut a lone, red-robed figure behind the bench: Judge Iain Bonomy.

When is a defendant no longer a defendant?

We were reminded that we were not back in the early 2000s when Bonomy’s soft, Scottish lilt came through our earphones to let us know that his judicial colleagues Mustapha El Baaj and Margaret deGuzman were joining via video link, as was Kabuga himself. We in the gallery could not see this, as the screens which would normally show us the courtroom, including its virtual participants, were switched off. As the voice of prosecutor Rupert Elderkin – also present virtually – reached my ears during the parties’ introductions, my headset switched itself off. I soon realised that I had to press a button every 30 to 45 seconds to prevent this, and after a few confusing minutes of jumping between English and French recordings, I settled for the volume button. The rest of the status conference thus came through my ears as though I was sitting on a swing set: with voices getting incrementally louder, and then quieter again. During a stint of private session, I learned through a whisper that it was a gallery-wide problem, and that we had a room full of dying headsets.

The status conference itself was both surprisingly public, and surprisingly informative. Judge Bonomy seems to hold a personal, poorly hidden distaste for both inefficient justice and private sessions, making him instantly popular among those of us in the gallery. He began by giving us, “the public”, an overview of updates, about the work that has been going on “tirelessly” behind the scenes. In reports filed in April and June this year, an “expert in critical care medicine” has found Félicien Kabuga not “generally fit to fly”. Considering he was unfit, in 2022, to be flown to Arusha (Tanzania) for a trial closer to the site of his alleged crimes, this is unsurprising. But these updates did give us a further insight into the now-90-or-92-year old’s deteriorating condition. The critical care expert noted Kabuga’s “physical frailty, coexisting diseases” and “medication”, would make a flight to somewhere as far away as Rwanda a major risk. The Prosecution, in a fit of either desperation or prosecutorial optimism, seems to think that this risk can be mitigated. Though the judges have yet to make a decision since the report of June 2025, Elderkin’s team made a filing on 9 September re-arguing that the best (and only) option for Kabuga is Rwanda. Bonomy, with his trademark wry tone, made a point of announcing that there was “no utility to this filing”, and that “to the extent that this submission is a motion, it is denied”. We all – Elderkin included – must await the judges’ decision on the matter.

Two unexpected and more unusual public session updates followed this. First, the Registry informed the Court that it was in the process of recovering Kabuga’s frozen assets to pay for legal fees. Unfortunately two planned meetings for early September, one “high-level” and one “technical”, with the unnamed State in which Kabuga’s assets rest, were called off at the last minute due to that State’s “prevailing political circumstances”. The mystique of this pronouncement was diminished somewhat by the audible whispers of “that’s gotta be France” that rippled across the gallery.

Second, we heard from Kabuga’s counsel Emmanuel Altit about two European states who had originally rejected Kabuga’s request to be released on their territory, but with whom further conversations were now ongoing. One of these states remained unnamed, but the second – France – was for the first time publicly discussed. Altit said that France had recently denied Kabuga’s request through the courts, stating that Kabuga as an individual was not in a position to make such a request, and that it must be done through the Mechanism as a “diplomatic entity”. Altit expects this to be overturned on appeal, but that this procedure could take up to 8 or 10 more months.

Unusually, for adversarial international criminal justice proceedings, the Prosecution seems to be largely irrelevant to the Court’s current task: finally finding an end for this Kabuga-limbo. Elderkin’s disembodied voice interjected only twice, both times to emphasise that he could “be brief”, and then say not much of anything, while his Hague-based colleagues sat in stoic silence. One of them was typing on his phone. Bonomy reiterated that all the Court’s actors are working “tirelessly” to secure Kabuga’s release, and lambasted “the unwillingness of certain European states to accept him on their territory”. When is a defendant no longer a defendant? For the states that claim to champion international justice and the rule of law, it seems that the lack of a conviction is not enough. Kabuga – like the other ICTR defendants who were either acquitted or have served their sentences, and are now trapped in Niger – is being consistently reminded that legal justice is, for some states, still not enough, and that political justice marches to the beat of its own drum. While an end for Kabuga may be approaching, it seems unlikely that this will be our last status conference.

When is a court no longer a court?

It will, however, be the last one in Courtroom 1. As the proceedings drew to a close, Bonomy made the unexpected announcement that this session would be the last time, ever, that a trial chamber sits in “this storied and historic courtroom”. Future hearings about Kabuga will be held in a “modified conference room”, he said, with a slight smile that could easily have been mistaken for a grimace. Without mentioning what is to become of Courtroom 1, he ended by reflecting on the hundreds of people who have worked within its walls since 1993 – security guards, interpreters, registry officials, judges, witnesses, victims, prosecution, defence, defendants – “all in pursuit of fairness, justice, and truth”. For Bonomy, a court is more than its arena: it is “at its heart simply a forum where arguments are made, evidence is heard, and decisions are made”.

As Bonomy stood, and the curtains lowered, the public gallery was briefly, unusually, silent. Then: an explosion of nostalgia. My neighbour exclaimed that he had spent hundreds of hours in this gallery, covering trials. Further back, other journalists spoke of the people they had seen sitting in those chairs that would now not be used again. “I spent my 20s at this court”, said one of them. The room had been formative not only for law and for justice, but for careers, lives, and stories. When I posted about Bonomy’s announcement online after the hearing, I received surprisingly emotional reflections from friends, colleagues, and people I had never met. For all, the space signified something bigger, and perhaps something that they now worry we might not see again: a concerted, widespread effort to achieve ‘justice’, whatever that may mean.

What makes a court a court? Undoubtedly, it is the people who populate it. But such forums for arguments, evidence, and decisions must still be designated spaces, often imbued with the pomp and circumstance of statutes, treaties, and rules, where individuals come together for that specific purpose. Courts are spaces that facilitate the interactions that – question by question, answer by answer, argument by argument, submission by submission – make up international criminal justice. They also hold all the emotions that are generated by those interactions, and the difficulty of narrating, prosecuting, and judging mass violence. The closure of the ICTY and IRMCT’s Courtroom 1 marks the extinction of one such space, which has held the weight of its fair share of expectations, emotions, and justice. Will it be allowed to remain – if no longer a driver of justice – as a memory of, or testament to, its past, like Nuremberg’s Courtroom 600? Or will it disappear altogether? Its eventual fate may act as a sign of our times: lacking both the justice aspiration of 1945 and the justice idealism of 1993. Bonomy did not speak to the courtroom’s future. Perhaps he did not know.

Lucy J. Gaynor is PhD Researcher at University of Amsterdam and NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust, and Genocide Studies, examining the construction of historical narratives within international criminal trials.