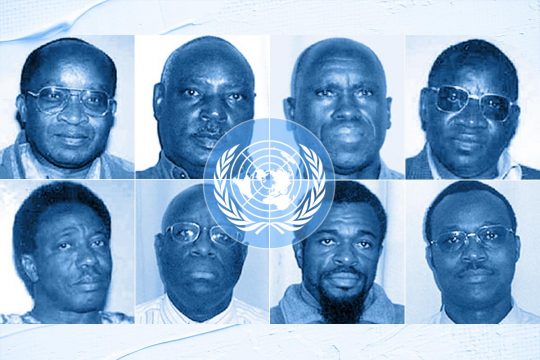

There has been stalemate for six months. On December 5, four ICTR acquitted persons - Prosper Mugiraneza, Protais Zigiranyirazo, François-Xavier Nzuwonemeye and André Ntagerura - and four convicts released after serving their sentences - Anatole Nsengiyumva, Tharcisse Muvunyi, Alphonse Nteziryayo and Innocent Sagahutu - left their “safe house” in Arusha, Tanzania, keen to rebuild their lives in Niamey, Niger. After many years of waiting for a host country, the UN said it had finally found them a permanent place of refuge.

Then everything went wrong. At the end of December, the Niger authorities reversed their position, declaring the agreement signed with the UN a month before null and void and ordering the Rwandans’ immediate expulsion, before agreeing to temporarily suspend the decision. Tanzania expressed its refusal to take them back. Since then, nothing has moved.

Deprived of their papers since December 25, 2021 and watched by police officers who have surrounded their residence, none of the eight Rwandans has set foot outside except for a medical emergency. "A restaurant owner comes to sell us food, while a boy comes every morning to run errands for us in town," said Innocent Sagahutu, contacted by phone.

"If I had to choose, I would definitely choose the UNDF [United Nations Detention Facility in Arusha]," he adds. "Since the beginning of March, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has been granted permission to visit us as they do for prisoners all over the world." The former Rwandan army captain, now 60, who served 15 years in jail in Arusha for his role in the 1994 Rwandan genocide, has just received assistance from the ICRC. "I was seriously ill and was taken to hospital, where I learned that the ICRC would pay for my treatment. When the doctors prescribe us medicine, the ICRC buys it for us and brings it to our prison here."

Niger's rejection

The "migrants" without papers in Niamey have (re)adopted the vocabulary of prison. After what happened to them in December, they want to be evacuated as soon as possible to a third country and have made several such to the UN Mechanism, which took over the residual tasks of ICTR after its official closure in 2015.

But evacuated to where? In Arusha, the UN registry refuses to give answers on the progress of negotiations it is currently conducting with Niger or another potential resettlement country. "It’s got nothing to say," replied one of the prisoners in Niamey, who requested anonymity. "Either the registry is not up to it, or it’s sold out, or both. It says it’s still trying to convince Niger to change its mind and honour the agreement [of late 2021 on taking in the ICTR eight], and that if Niger persists in its refusal, it will find another place for us. But the registry never says what it’s doing."

Responding via lawyers to the UN judge who ordered Niger to suspend its expulsion decree, the Niger authorities insisted on January 14 that: "As well as for diplomatic reasons about which the Niger government is entitled to keep silent, it has been established that the presence of the applicants on Nigerien territory constitutes a threat and a disturbance of public order."

On behalf of the government, lawyer Aïssatou Zada criticized the UN judge's order as "untimely”. According to Niamey, any dispute arising from the so-called resettlement agreement between Niger and the UN must be settled "by negotiation or by a mutually agreed means”. In its view, the Mechanism is not competent to settle the matter. But it said nothing on the fact that Niger’s unilateral decision on expulsion may have been a violation of the agreement.

Repeated orders from the judge and referrals to the UN Security Council by the President of the Mechanism have been in vain.

Tanzania refuses to take them back

Given the standoff with Niger, as well as multiple cries of alarm and requests for immediate evacuation, the judge turned to Tanzania. He ordered the Registrar to “immediately take all necessary measures (…) for the Relocated Persons to be returned to the Arusha branch of the Mechanism on a temporary basis, until their transfer to another State”.

But the Tanzanian government said its obligation to facilitate the temporary stay of released or acquitted persons under its headquarters agreement with the UN had ended with their transfer to Niger. There was no question of bringing them back.

Faced with the impasse, the Mechanism judge ordered the Registrar to "make more efforts and actively engage with Niger and other possible relocation States until an acceptable resolution of this matter is found in order to ensure the respect for the fundamental rights of the relocated persons" and asked Niger to "adhere to the rule of law in relation to the situation of the relocated persons and ensure their safety and welfare until a resolution is found”.

Judicial failure, diplomatic dead end

According to the judge, "at present, all appropriate and available judicial relief has been extended to the Relocated Persons and the primary avenue for redressing this crisis lies in political, diplomatic, and administrative efforts undertaken by the Registrar under the supervision of the President and with the President’s referral of this matter to the Security Council.”

The Niamey prisoners thought it necessary to inform the UN Security Council of Niger's failure to meet its obligations, violating the agreement on their relocation. They also sought a new order requiring Tanzania to facilitate their return to its territory, and a hearing before the Mechanism in The Hague or, alternatively, in Arusha, in their presence. But on May 27, the Appeals Chamber of the Mechanism rejected this request.

"This is a profound disappointment," said lawyer Peter Robinson, who is representing Nzuwonemeye. "We gave the judges a way to rescue these men by bringing them to The Hague or Arusha for an oral hearing on the appeal or a status conference. The [Mechanism's] headquarters agreements with the Netherlands and Tanzania obligate them to allow persons on their territory when their presence at the seat of the Mechanism is required. But the Appeals Chamber denied our appeal, ruling that the Mechanism's duty to ensure their welfare extended only to encouraging a diplomatic solution."

Exit Bicamumpaka

Defence counsel is working on three fronts, the US attorney explains. On the judicial front, they are pushing for judges to use all powers at their disposal to rescue these men. That front, however, seems to be exhausted. Secondly, they are working on the diplomatic front, using "our own contacts with various countries to persuade them to work with the Registrar and take our clients”. Robinson says these clients “are willing to go anywhere except Rwanda”. Thirdly, they are working with lawyers in Niamey to obtain, in the meantime, the withdrawal the police and an end to their clients’ house arrest.

But caution is the order of the day. "Frankly, we are afraid to push Niger too hard. Our clients fear that if we do, the government might try to expel them to Rwanda," said Robinson. He calls this "a mammoth injustice". "My client was acquitted and remains a prisoner eight years later. That is unacceptable," he complains.

Of the nine Rwandans who were offered the chance to go to Niger last December, only one, former Rwandan foreign minister Jérôme Bicamumpaka, firmly turned the offer down. Bicamumpaka, who was acquitted in 2011 after more than 12 years in prison, was ill. He died in a hospital in Kenya on May 19 at the age of 64. Canada, where his family obtained citizenship, had not allowed him on its soil. On May 28, it agreed to receive his remains.