Anatoliy Derevyanko, 56, is from the village of Verbivka, Balakliya district. According to the prosecution, the chief engineer profited from the Russian occupation to become self-proclaimed manager during occupation of Balakliya, eastern Ukraine. The defence says was only taking care of his team and protecting economic property.

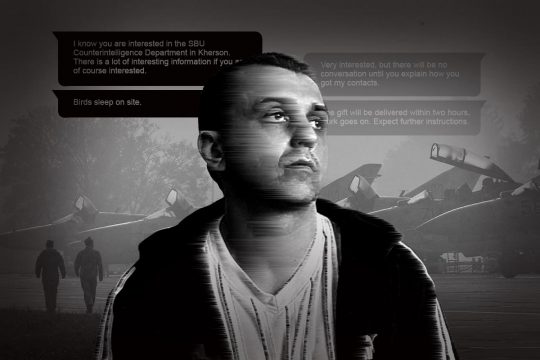

The District Court of Kharkiv has been assigned to Derevyanko's case since May 2023. At the end of January and start of February, witnesses were questioned. The media's attention to such a seemingly minor case surprises both the prosecutor and the defence lawyer. But neither they nor the accused have any objection to the presence of a journalist. Before the judge's arrival, Derevyanko agrees to be photographed, although he says he is not in the best shape for a photo.

"No one was forcing me"

Derevyanko has been working for the Balakliya Grain Storage Company (GSC) since the 2000s. He did not leave during the Russian occupation, which lasted from March to September 2022. After the manager quit, the chief engineer continued to go to work. Other employees did the same. There was still grain in this storage facility they call “the elevator”. The Balakliya Grain Storage Company was one of the most prosperous firms in the area. In addition to the elevator, its agricultural holding under the umbrella of "Megabank" (declared insolvent in June 2022 and currently in liquidation) included a bread-making plant and a mill.

"There was normal work to preserve the material integrity of the company and provide the staff with humanitarian aid, so to speak, and salaries,” Derevyanko told the court. “But it was all within the framework of Ukrainian legislation as I understand it. There was no cooperation with the Russian Federation. No one was forcing me. All of the managers had left, the company was abandoned, but people were there, people were working,"

"We had to find a way to survive"

Derevyanko's colleagues are now called as witnesses in the case. They were questioned in the Kharkiv court at the prosecution’s request. Larysa Nazarenko, a health and safety engineer, was the first to answer the prosecutor's questions. She says she did not leave Balakliya because of her elderly parents, who were afraid of looting.

"Please tell us, did you continue to work at the Balakliya GSC during the occupation?" asks the prosecutor.

“There were only a few guys who stayed there on their own initiative, who would, let's just say, close the gates and preserve the grain,” replied Nazarenko. “We had a new bucket elevator nearby, and it was looted by people -- our people, Ukrainian people! And our guys, the elevator workers, on their own initiative, were protecting the property during this entire period. As for me, I did not go there until July 19."

Meanwhile, the occupiers planned to resume the elevator’s functioning on their own terms. Nazarenko heard rumours about the possible reopening of the company. She thought it was a chance to provide for her family.

"The money I still had in my bank account was blocked,” Nazarenko continues. “We were living one day at a time. We knew we had to push through it somehow, for us and our families. We didn't know when we would be liberated, we had to find a way to survive. And to do so, we had to get money from somewhere."

She recalls her first arrival at the grain company.

"We have a very large cherry tree there. I would pick cherries and sell them in jars to buy some things to make soup or borscht. I did not believe that the war was coming and I did not store supplies, unlike some people did with buckwheat, salt, and so on. I lived from paycheck to paycheck. And then word-of-mouth got to us that it was possible they would reopen.

"I went to the elevator to earn as much as a jar of pâté,” says Nazarenko. “Winter was coming, and we knew it would be hard. One day we all came. A representative of, let's call it, the Russian Federation came with certain assistants. He told us something about the elevator to reopen someday. They didn't really understand what to do with it, how it would be and what would happen, and suggested we come back to work."

"He was like the head of our gang"

Nazarenko mentioned another motive for coming to the elevator. The Internet was functioning in one of the buildings and her son, who was about to graduate, needed to apply to the university remotely, using a simplified procedure for applicants from the occupied territories without completing the external independent evaluation. "There was a question of where to get the Internet for this purpose. We had good 4G Internet at the elevator. And this coincided with the time of university admissions," she recalls.

"We were all, you know, like a family,” she continued. “We did whatever we had to do. We would come and go. And thank God, they did not kill us. We did not have any responsibilities per se. We were on our own. We would preserve what was left in the elevator. We would weld shut the storages to prevent them from being looted. And he [Derevyanko] was like the head of our gang," Nazarenko says.

These were exactly the words the prosecutor was waiting for.

"In your testimony, you stated, in a manner similar to what you have just told the court, that Anatoliy Ivanovych Derevyanko took power into his own hands. In other words, he was in charge. Is this true? I have just read your testimony."

"Well, again, he didn't give me any tasks. And he didn't require anything from me. I told you, we were one family, as equals,” Nazarenko replies. “Yes, we somehow mutually realized that he was in charge, or not in charge. We didn't consider it to be work."

"He's a pro-Ukrainian, one of our own"

Derevyanko's defence lawyer is interested in whether the Balakliya GSC worked with Russian entrepreneurs or the military.

"No, not once have I seen Anatoly Ivanovych with the Russian military. He works only for the benefit of our company, only with Ukrainians. He's a pro-Ukrainian. Never in my life will I believe that he is a collaborator," Nazarenko says.

Anatoliy Derevyanko smiles behind the glass wall.

Witness Oleksandr Globa waves at the screen from the Balakliya district court. This is his way of greeting the participants of the trial at the beginning of the interrogation. But the independent entrepreneur from Balakliya is not very forthcoming. The prosecutor has to pull answers out of this witness.

In the summer of 2022, Globa sent his harvest to the elevator of the Balakliya Grain Storage Company for storage.

"I had no facility for storage. I needed to rent it somewhere for two months," he explains.

The prosecutor refers to a document indicating that the entrepreneur concluded a contract with the GSC on August 3, 2022.

"Well, then, on the 3rd," Globa agrees.

The prosecutor is interested in the details of the contract: who signed the contract and under what circumstances.

"Well, probably the manager or something, how would I know who was there? The office girls gave me the contract."

Globa says that he did not see who signed the contract on behalf of Balakliya GSC.

"The investigator asked you during the pre-trial investigation where and who was present when you signed this contract. It is written that you went to Derevyanko's office and he personally signed the contract with you. And now you are literally changing your testimony," says the prosecutor.

"I'm telling you that the girls gave it to me! Derevyanko was not there."

Globa also failed to recall what language the contract was written in.

"You didn't collaborate with the occupation authorities, did you?" the defence lawyer asks.

"No, of course not."

"When you handed over the grain, were there any military personnel on the premises?"

"No, there were none."

"And Russian symbols?"

"I didn't see any, I don't even remember, but I think there weren't any."

After de-occupation, farmers got their grain back

Defence lawyer Serhiy Chub says none of the prosecution witnesses interrogated so far has confirmed Derevyanko's collaboration with the occupation authorities.

"They all confirm that employees who came to the elevator came with the sole purpose of preserving the property. The manager of the company, as he stated, was under pressure and left the company, and the employees remained on their own. They knew that if they didn't return, didn't organize security, didn't organize some kind of activity of the company, it would be looted. Those entrepreneurs did not bring their grain there to give it to the Russians or for any commercial activity. They brought it because there were no other places to store it in," the defence lawyer says.

"The grain was received from Ukrainian farmers, and everything was preserved. And after the de-occupation, the farmers got it back. These are small volumes, only 500 tons. And as for what was left from previous harvests, large volumes, it was all preserved as well," the accused told MediaPort.

"Were the documents signed in Russian?"

"We signed contracts with farmers whose grain we took for storage. No contracts were signed with the Russian side. These were Ukrainian contracts, the same as in previous years. Of course, we translated the documents into Russian, because it was better for the farmers in order to transport their grain," says Derevyanko.

When asked how he feels about the charges in general, Derevyanko answers: "I think the court will sort it out. I hope so."

The court of Kharkiv continues to hear witnesses in this case.

This report is part of our coverage of war crimes justice produced in partnership with Ukrainian journalists. A first version of this article was published on the "Mediaport" website.