JUSTICE INFO IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS

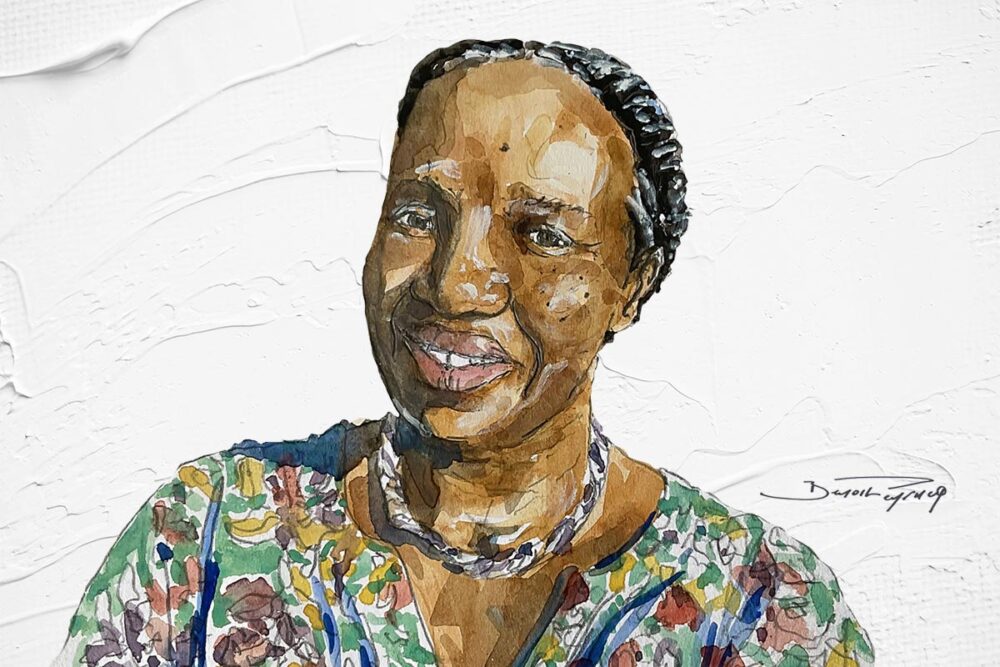

Assumpta Mugiraneza

Co-founder and director of the IRIBA Center for Multimedia Heritage

Assumpta Mugiraneza, 57, is the co-founder and director of the IRIBA Center for Multimedia Heritage in Kigali. With rare freedom of speech, she recounts the construction of memory after the genocide of the Tutsis in Rwanda in 1994. She talks about Rwandan “memories” and the limited space offered for all of these memories to express themselves, while she invites us to reconsider gacaca justice with more sobriety.

JUSTICE INFO: During a workshop at the IRIBA Center, you said that “the history of memory in Rwanda is a history of tensions that must not be forgotten”. At the time of the 30th commemorations of the Tutsi genocide in 1994, could you give us several examples and remind us the various stages of these tensions?

ASSUMPTA MUGIRANEZA: We have to go back to what this genocide is. It’s a proximity genocide. It happens between brothers, between neighbors. It does not even fear sacred relationships “between servants of God”. When the nuns have priests slaughtered, when the doctors finish off the sick, it is not something that can be quickly overlooked. This genocide has so much entered into the interstices of our existence that we cannot easily find someone who agrees to think about it within this complexity. The memory of the genocide is a finger pointed towards our neighbor. How can we talk about unity when the blast has shattered everything? How can we imagine life? The memory of the genocide was inscribed in this impossible context.

For the survivors who were in positions of responsibility, there were questions about the difficulty of being both in Ibuka and in the government: perhaps it was necessary to be on one side or on the other."

Do you remember the first times when the commemoration began and how it evolved, how it was constructed?

How it is negotiated, I would say. I prefer the term negotiation, even if sometimes negotiation seems to impose its own rules. In April 1995, there was no supra structure that organized the meetings. It was often widows who would get together. Above all, there was the need to get together among people who understood each other. People weren't really at home anymore. Those who could not do otherwise, who had no connections in towns a little further away, used to staydclose to their hill. The survivors were often regrouped together where there was a small cabaret, a small trading center, so that they could be protected and because returning home, alone, was not yet an option. Even in Kigali, they needed to regroup somewhere. No house was inhabited by one sole family. It was a sort of gathering to cry together.

At that time, Hutus who had escaped massacres by their own people because they were not extremists were still free to speak. Some said: “One of two things, either I remain Hutu but these people who are in Congo can no longer bear the same name as me, or they keep this name and I let it go”.

Of course, the genocide was also a state affair. The state was painfully coming together. It had begun to play its role as a state, but it did not interfere much with these individual initiatives. For the survivors who were in positions of responsibility, there were questions about the difficulty of being both in Ibuka [the main association of Tutsi survivors, created in the aftermath of the genocide] and in the government: perhaps it was necessary to be on one side or on the other. Why ? I'm mainly talking about the RPF [the Rwandan Patriotic Front, a predominantly Tutsi rebellion that won the war in July 1994 and put an end to the genocide]. It is not that it was in denial of the genocide but it did not yet understand what would be the weight of this crime that it had just stopped and the seriousness of which it recognized in the facts, but not from an international and long-term perspective.

How can we imagine a unity government just after the genocide? How should Pastor Bizimungu [the president of Rwanda from 1994 to 2000] negotiate both the fact that he is a Hutu, from the North, from the region of Habyarimana [the Rwandan president who died in the attack against his plane, on April 6, 1994], and that he has a Tutsi wife, has “betrayed” the Habyarimana regime, joined the RPF, become president, and sees what was done to the Tutsis but also to the Hutus at home, and in at the same time he has relatives of his family who committed the genocide? What is this man who must be the head of a state when he himself is a tiny Rwanda? It took a long time for the official Rwanda to realize that genocide is not something that can be resolved in a few days. Just because we stopped it doesn't mean it is resolved.

This is where we must do the work of remembering our memory. For a long time, there was some tension, for example over how to name this thing. The severity of the injury, the blatant injustice, the innocence of the victims, made people feel damaged. Anyone who was in Rwanda at the time had to step over bodies. How can my legs go over a human being's remains without shaking? I think we didn't have enough time to accept this fear that was coming in. It’s like we’re pouring concrete inside ourselves and still seeing. This tension is there, from the start. And before this incomprehension had even time to sink in, we saw the return of refugees [at the end of 1996, hundreds of thousands of Hutu refugees in neighboring Zaïre – today's DRC – massively returned to Rwanda after a Rwandan army offensive to dismantle the camps on its border]. God in heaven... This vision, even Spielberg cannot turn it into fiction!

With the 10 years, we start to see the state worrying about how things are going. Commemorations were often the space where trauma was expressed and that scared the hell out of everyone."

You mention a double movement of commemoration, at level of the people and at the level of the state. Do you see this double movement acting in parallel today?

No, it was before. With the 10 years, we start to see the Rwandan state worrying about how things are going. Commemorations were often the space where trauma was expressed and that scared the hell out of everyone. With the two Congo wars [1996-1997 and 1998-2002], the government had begun to understand how difficult it was to ignore negationism, for example. In the meantime, the unity government had, I won't say, burst into pieces, but we had seen its limits. Even if you are a good guy, if you are Hutu, it is difficult to keep the balance, to support internal and external tension, on yourself and in your family. Alphonse Nkubito [minister of Justice from 1994 to 1995], Anastase Gasana [minister of Foreign Affairs from 1994 to 1999, then in charge of other portfolios until 2001], and others decided to leave. Because the genocide had shattered us. So after ten years, the Memorial office at the Ministry of Culture and Sports will take up more and more space, in collaboration with Ibuka, and they will try to structure things. It's a negotiation. Then the National Commission for the Fight against Genocide (CNLG) imposed its way of doing things, at the expense of many people. A somewhat tight, I would even say narrow, framework will be set up.

For example, the CNLG tried to ban memory songs. A commissioner explained to us that songs - like “Mbaze nde”, where a Rwandan woman recounts what she saw of the genocide, or Mariya-Yohana's song, “Nyibutsa Nkwibutse - Remind me to remind you the memory”, which is an extraordinary portrait of what it's like to survive genocide, and others – were outdated, that they were songs that made us fall backwards, instead of moving forward towards hope. It was a difficult time, wanting to nationalize the question of memory too much. During those ten years, Ibuka lost its influence within the society, the voice of Avega [the Association of Widows of the Genocide] was no longer very audible, the NGOs preferred to settle and our diplomat friends preferred not to have any problems with Rwanda. At that time, the alternative speech, the thinking before doing, were really reduced to almost nothing.

When Bizimungu was cast away and replaced by President Kagame in 2000, one of the debates that animated people's minds was precisely the relationship to the genocide. Some people considered that there was too much about the genocide. The debates were so tense. Some thought that memory was an obstacle to the political life of this country. I still hear someone say: “Maybe you can consider abolishing Ibuka but if Ibuka disappeared, would the reasons for its existence disappear too?”

Today, the CNGL, the National Unity and Reconciliation Commission, the Genocide Survivors Support and Assistance Fund, the commission which takes care of national heroes, have all been grouped into one ministry. The top of the power indicated that policing the memory too much was not necessary. Those who insisted on having independent spaces want to be able to have a commemoration between people who have something in common. Why should a widow necessarily cry next to her executioner? The policy of memory must be reinvented, renegotiated. We must dare to question our practices. The imagination must work fully.

You always emphasize that there is not one memory but several memories…

Yes, there are several memories, fortunately. We would like one memory but there are memories. I defy anyone to say that, even within a family, we do have the same memory. I wasn't in Kigali, that's why I'm alive. But the fact that I was not in Kigali led members of my family to talk to me more easily than one to another. And when they spoke to me, I took notes because I was relentlessly trying to understand how this had been possible, within my society, where I grew up and was happy. I grew up on a hill that was not ours but never knowing that people could be terribly angry with me because I was Tutsi. I never really suffered much. When I opened my eyes to my particular status as a Tutsi, it was when I was unable to access university even though I had the points to qualify.

Take the fighters of the Rwandan Armed Forces. Some were not very willing, others had taken up the Hutu Power cause all the way till the end, some tried to protect, others preferred to become bastards, some had wives who told them why are you killing the neighbors?, others had women who pushed them. Some had the misfortune, which was to be their good luck, to be taken very early and to join solidarity camps, others left to go to Congo. You arrived quite early on in Rwanda: do you remember how the camps looked like? Do people remember the pain of these little bodies in the mats tossed around by public works emachinery?

President Kagame, during the commemoration this month, thanked Congo and Tanzania for welcoming and protecting Rwandans [around two million Rwandans had found refuge in these two bordering countries in July 1994, driven in their flight by the defeated Rwandan army]. I wanted to tell everyone: do you remember that it was Rwandans who were dying and that they were new victims of the extremist Hutu Power ideology and of the extreme nature of the genocidal apparatus which had embarked them there?

All these memories live within us and not all of them can be shared. Because there are intimate things. And perhaps because the nation has certainly built a space of memory but we should start talking about it within families."

Are all these memories part of the tensions new generations must live with or is it the burden of your generation?

In fact, all these memories live within us and not all of them can be shared. Because there are intimate things. And perhaps because the nation has certainly built a space of memory for the crime of genocide but we should start talking about it within families. I had the chance to contribute to writing the fundamental texts of the Ndi Umunyarwanda program. They were everyone’s memories. It was said: to return to one's identity as a Rwandan, one must be able to share one's own identities, one's journeys which start from the time when everyone seemed to give up their identity as a Rwandan to be reduced to their identity as a Hutu, a Tutsi, a Twa, someone from the North, etc. It was one of the pillars. The other pillar was to speak and listen. We should have been able to talk about the memory of the refugee camps. But as too big a knot had already been formed above the heads of our leaders – “double genocide”, “genocide in the Congo”, etc. – by talking about these memories, without control, people risked thinking that this memory and that of the genocide were the same thing. We would have needed more time, to go at a slower pace. The third pillar was to think about what forgiveness can mean in our society.

These memories are first and foremost those of our generation. When we began to build the memory of the genocide in the public space, we forgot to make the same efforts in other spaces. We walked with something schematic: you, the families of the victims and the executioners, talk to each other, reconcile. But for a man who spent three months slaughtering and fled with the arrival of the RPF, leaving his wife behind with eight children, how do we reconcile this family? No one ever talked about the injuries in Congo camps. In 1998, a woman returning from Congo told me this: “We knew when they raped Tutsi women but then, to see them entering the armored vehicles [name of the shelters in the refugee camps] and throwing themselves on me, then whereas he is my brother and companion in misery, I will never understand it.” Who was talking about these rapes, these children who died in Congo? I have never forgotten the little mats, I see them regularly. I have not forgotten and I still feel angry against those who showed them as a spectacle, against the machines that threw [the bodies], against the guy who spread the lime, against the reports which said “look, it is again a catastrophe”, without ever asking the question: how did we get to this point?

The memories of Rwanda are also those of political spaces. We have eaten easy propaganda up to our ears."

You said that you have to be creative to set up spaces of memory today. What are they today?

Memory is a story, which we can share or keep to ourselves. We can do it by speaking, by creating art, by writing, there are a thousand and one ways. A major national event can be a trigger but this society needs spaces to free speech. We must accept narratives, without letting them be held hostage by the failings that have accompanied our misfortune. We owe these memories to our children.

The the National Unity and Reconciliation Commission had tried. But often, there is no know-how, no tools, maybe not the courage, the will to change certain things. It needs courage. We must accept this weight that our history places on the shoulders of adults in Rwanda.

The memories of Rwanda are also those of political spaces. We have eaten easy propaganda up to our ears. We who grew up in Rwanda, we have eaten so much propaganda that we would almost need a stomach pump to avoid repeating that. There is no effort made to deconstruct. I am always amazed when I see people having fun displaying the easy slogan. I say: my friends, no! No !

Perhaps there is not enough intellectual courage in the country. Perhaps because we are injured, the blast was such that everyone fell on their own side and we have not yet “returned”.

Would a space for multiple narratives be too sensitive?

It will always be sensitive. I often work with young people, I know that they bring new things that would not have been possible for my generation. But they are still few. There are more spaces but not necessarily more support. Although we still have resources that we do not suspect. If there was a time when we should have been afraid and said there’s no point in trying, it was right after the genocide. If we survived that period of time, we can survive everything else.

Young people are innocent, our children are innocent, even the child of the worst killer is innocent of the genocide and, for that, he can invent his future differently. What bothers me is that we don't help them and that we risk indoctrinating them. We, the adults of Rwanda, we have a find it easy to applaud or to follow. We don't want to get tired and conscientiously take our place. There is laziness to think. We prefer to say it is fear. If enough of us had said no, if we had been more courageous, the genocide would not have happened, even if there would have been massacres. If the Rwandans had said no. Today, I am not saying that we must say no in the same terms, but we have the duty to say: is what I am being asked to do the right thing to do?

By talking too much, you risk putting yourself in danger, that’s a reality. But the fact that you have to speak to heal, that you have to dare to open your wound to heal, also remains a reality."

We heard you say: “In Rwanda, a family where we don’t talk dies.” But right after you, another person said: “There are many things left unsaid, many ways to making the danger loom. Rwandans are experts in non-verbal communication.” How do you reconcile these two realities?

The Rwandan universe is almost like the Bible. In the Bible, it is said that when you want to pray to your heavenly Father, you go to your room, you double-lock it and you pray in the secret of your heart. What you gave with your right hand, the left hand must not know. It’s a way of saying: be as discreet as possible. Life is the in-between. There is a proverb that says: “A family that does not take the time to sometimes revisit its secrets ends up dying.” Under certain conditions, families are forced to sit down and wash their dirty laundry, at the risk of dying out. Another proverb says: “He who does not speak with his father cannot know the words left to him by his grandfather.” In fact, it is the power of transmission. It is also said: “When you want to heal from an illness, you must be able to show it,” and “a heart steeped in pain cannot unravel the words.” There is all that, but it is knowledge ignored by non-Rwandan people. The mind of Rwandans is not Cartesian, it is complexity. It is a stratified universe, but not by layers, by interweaving. As a result, being modest remains a value. By talking too much, you risk putting yourself in danger, that’s a reality. But the fact that you have to speak to heal, that you have to dare to open your wound to heal, also remains a reality. The fault would be to be one side only. We need adults who are convinced that when you say what is wrong, it is not because you do not love the country but rather because “he who loves well punishes well”. Let's dare to speak, let's dare taking this risk.

Do you ever worry about an overflow of memory?

Rather the clumsy demonstrations around memory. Our memories are already saturated.

What do you mean by clumsy?

It is, for example, not daring to speak about my memories and, since I can't deal with it anymore, starting to hold speeches on memory and espousing it as if the memory of the genocide were my most precious possession - whereas ultimately, that is not what inhabits me. Or fighting the memory of the genocide as if, if the genocide were to be silenced, all my torments would be healed. The instrumentalization of memory is lurking near us. Not only those who are for it, but those who spend their time denying the genocide, saying that we are doing too much.

You have worked a lot on justice and gacaca. During a workshop at your center, a young person, a child at the time of the genocide, said: “Of course we were able to carry out many trials, but there is also what the gacaca could not achieve and that I did not know. Gacaca are a source of pride for our country but, deep down, we don’t know what happened.”

He spoke more for young people. When he speaks like this, he talks about a reality which is at the very heart of what we experience at the Iriba center. We see young people, 20-25 years old, who proclaim their pride about the superb achievement of our country which is called gacaca and who, after watching Anne Aghion's film, “My Neighbor, My Killer”, say that is not possible. They discover that gacaca is not a smooth thing, covered with a layer of shiny gold. Gacaca imposed a very heavy cost on society. Accepting gacaca, for the victims, was a horror. How can we start from the idea that, if someone confesses, their sentence will be reduced to almost nothing? Why would I go and talk to these people? Why should I sit with them? It has also a gigantic cost for the guilty. You remember this killer who said: I didn't do much, I just killed three children, while they were destroying the house I was burying them. In his way of speaking, he said “I was calmly”…

Gacaca has cost us so much that we cannot accept gacaca to be reduced to a program which went well, which would have judged almost two million cases and about which Rwandans would be 96% satisfied. No. Long before we concluded the gacaca, people basically told me: “The gacaca can close, but we will always need our gacaca because not everything has been settled”. A Hutu woman from the North who had watched the film ended up saying: “As I watched these mothers talk about their killed children, I felt my stomach turn inside out.” She spoke of her child who died on the road when they were fleeing the progress of the RPF, of another who died in childbirth and of a child she had lost in the Congo. She went to find her husband in Congo and when the gacaca started, he fled. She said: “Looking at these ladies, I remember that I buried my three children, but I never had time to mourn them. And I told myself that my husband had fled the gacaca because he was afraid to answer for his crimes. I never had the opportunity to think that, I lived with resentment.” She is a Hutu woman who is facing her memory, shaken by an artistic work, the film.

It allowed Rwanda to admit that killing a Tutsi is a crime. The gacaca gave the opportunity to say it. The problem is when we start showing them off too much like a trophy."

So are you bothered by the way the gacaca are celebrated?

It's more than that. I find it distasteful. We don't have to celebrate. It's good, we were able to do it, it has allowed us to know certain things, it allowed Rwanda to sit down face to face, and admit that killing a Tutsi is a crime, in a country where we don't couldn't steal a soap from a market stall and get away with it. The gacaca gave the opportunity to say it. The problem is when we start showing them off too much like a trophy. In our workshops, we invited people to talk about their experience within gacaca, gacaca memories. Among the survivors, very few had completed the process. They hoped to at least have an account of the last hours of their loved ones, and if possible to know where were the bodies. When they saw that this was not likely to happen, they said ciao. Today, what we first put forward, because it is what our society lacks the most, is the information concerning the bodies that have been found. This happened sometimes, but so rarely. So, I'm being told “the truth has been revealed”: at what level? There were also practices where the criminals came to an agreement: I get along with you both, I take your crimes upon myself, we cannot be imprisoned twice at the same time. There was corruption, the inability to grasp the enormity of the crime. I would like this to be said, shared. Not because gacaca were a failure, but to say, like Hannah Arendt, that it is a crime that can neither be punished nor forgiven.

It bothers me because it was a hell of a lesson for us all. Rwanda did this against all odds. Now, you go to university and you ask people to tell you a little about the ICTR [International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, created by the UN], you will be surprised. The Gacaca, at least we talk about it. But the ICTR, today, there is no trace. Why? There is nothing, or almost nothing, to work with on the history of justice, whether it be gacaca justice, the first national trials, with the executions, or the ICTR. Justice deserves to get justice.

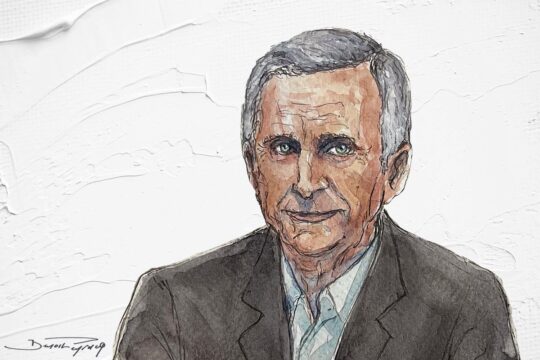

Interviewed by Thierry Cruvellier and Emmanuel Sehene Ruvugiro