“If you look at the Rome Statute, it's actually really disturbing to see how many articles you can go through and say, yes, that's a possible part of the International Criminal Court investigation” in Palestine, says Eitan Diamond of the International Humanitarian Law Center in Jerusalem. Omar Shakir from Human rights watch, an NGO, agrees that you can see “the full gamut of grave crimes,” being committed. However, since it became a member of the ICC in 2014 and the Court’s Office of the prosecutor opened first a preliminary examination and then a full investigation, the only arrest warrants so far have concerned alleged crimes connected to the October 2023 Hamas attack on Israel and the Israeli starvation of the Gaza Strip in 2024. That’s despite the mass of material concerning potential war crimes and crimes against humanity which has flowed liberally into the court from the United Nations, the Palestinian Authority and from NGOs.

Now there are reports of a request for further arrest warrants by the Office of the prosecutor in connection with the Israeli government policy of settlements in the West Bank. What other crimes could and should the Office of the Prosecutor be looking into? And how far are political pressures slowing down the ICC approach?

“There are a variety of legal, jurisdictional, factual challenges that can make some charges easier or harder than others to deal with,” says Shakir. “So then it becomes really a question of prosecutorial discretion, in terms of how do you adjudicate between these issues. The prosecutor has made it clear that they're going to focus obviously on the most serious crimes, and the most egregious perpetrators. That often means looking at those crimes for which the impact has been most significant but also looking at ones in which maybe the challenges on factual or jurisdictional grounds are less significant. And sometimes there are trade-offs right between those. There have been a lot of credible documentation of various war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide. It's a matter of how you triage all of that, and move forward.”

Why not genocide?

“Part of the explanation might be the evidentiary threshold; for some of these crimes there's quite a bit that you have to prove,” says Diamond. But “there's also, I suppose, a degree of institutional politics at play. I don't think there's much room to dispute that genocidal acts have been committed. The question, of course, is about whether you can prove the special intent. There’s quite a significant body of evidence to make a case that there was intent. The Office of the prosecutor might not have pursued this because I don't know if they feel confident that this is sufficient. However, I really don't think that the ICC is going to rush to prosecute anyone for genocide, because that's going to be too politically charged.”

“I think there are at least serious questions that should be posed about the ICC's apparent unwillingness to engage with this critical issue at this critical point in time,” says Mouin Rabbani, co-editor of Jadaliyya and senior analyst at the International Crisis Group. “I mean even rumours of an application for an arrest warrant on charges of genocide could actually have an impact on the ground because it would send a clear warning signal to, for example, the European Union and its member states. And put pressure on Israel.”

Why not apartheid?

A list of possible crimes against humanity is also part of the discussion on the scope of the ICC prosecutions. “We're seeing tens of thousands of people in the West Bank and millions of people in Gaza being moved about, displaced. So there might be grounds to say that the crime against humanity of forcible transfers, without grounds permitted under international law,” has been committed, says Diamond. The expert also points to “the reports coming out of detention facilities which suggest that torture is taking place in a kind of systematic way. Not just a prison guard who's sadistic and is abusing someone; it's something that's done systematically to many detainees.”

And then there’s the crime of apartheid. “There's been quite a bit of writing from many different sources saying that Israel maintains an apartheid regime in the occupied Palestinian territory. There's an element of intention in the Rome Statute definition. So even though it seems undeniable that there's different treatment of groups of people in the occupied territory, depending on their group affiliation – settlers are treated in a completely different way from Palestinians to the detriment of Palestinians – there might be a debate about whether that discrimination is done in order to perpetuate a regime of racial domination, which is one of the elements that you need to establish. But I think this could be a strong case, and many have argued the same,” says Diamond.

Settlements: “The prosecutor has absolutely no excuse”

“Some of the crimes have a long history,” reminds Diamond, including “the prohibition of the transfer by the occupying power of its own population into occupied territory, either directly or indirectly. I don't see how Israel can explain that it didn't do that. Certainly there seems to be a consensus internationally that Israel's settlement project entails a violation of this prohibition. Israel has certainly, if not directly, then at least indirectly facilitated the transfer of its own population into the occupied territory” – which constitutes a war crime.

Alongside apartheid, this is one of the two “cut and dry cases,” says Rabbani, “on which the prosecutor has absolutely no excuse not to have moved forward. He doesn't even need to investigate in the sense that every Israeli leader has been proclaiming settlement as part of their agenda and a political objective and a practical activity. So why in 2025 has he still not made any determination with regard to the settlement file, in which we're talking about indisputable systematic government policy?” And in which the recent advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice concerning the illegality of Israel's activities as an occupying power gives further authority in making the case, says Diamond.

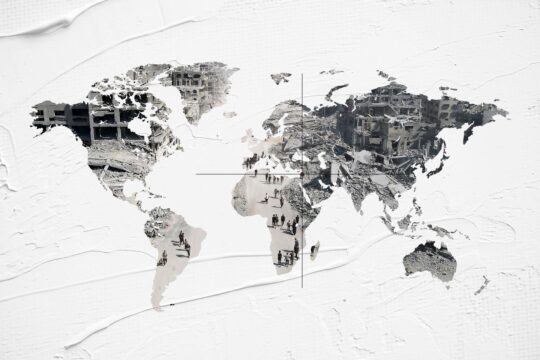

“I was just looking through the list of grave breaches” of the Geneva Conventions, “and you could make a case for pretty much every one of them,” says Diamond, now referring to war crimes. A very important one in the current phase of the conflict, he says, is “extensive destruction of property. Israel has, in addition to the infrastructure that it's destroyed when launching attacks in Gaza, destroyed whole neighborhoods, not in the process of or during the conduct of hostilities, but after acquiring control over an area – all these images of soldiers gleefully blowing up universities and other structures and recording it on TikTok or social media. So there's really extensive destruction of property in Gaza and also in the West Bank.”

Standing up to political pressure

There are the missing crimes, and there are the missing suspects. “It's not only that you could expand the number of crimes that were identified, but also the number of perpetrators,” says Diamond. “There's a lot of publicly available information, including statements made by officials, sometimes in their official capacity. Sometimes there's a kind of statement of policy that's self-incriminating. It's not just the Prime Minister and the former Minister of Defence. The current Minister of Defence even in his previous capacity [as Minister of Energy] has said the most horrendous things. So certainly there's an equally strong case to be made against him. A strong case could also be made against the Minister of National Security, Itamar Ben Gevir, who's responsible, among other things, for the prison service and the ill-treatment of people there. You could probably find many more both within the senior command of the military and amongst the leading politicians in the country.”

Rabbani sees the ICC prosecutor as playing politics “very deftly” and “dragging his feet”. “When he finally did issue applications for arrest warrants he made sure that he applied for more Palestinian than Israeli arrest warrants. And I think it's pretty clear that that reflected political considerations rather than the scale of the various crimes he was examining.” For Shakir the political challenges for the Office of the prosecutor come from “states who have shown over the course of months and years, double standards when it comes to commitment to international justice. The political challenges are there, and they're really on all international institutions that are working on Israel-Palestine. Palestinian issues, especially in the last 20 months, but much more generally, have become the litmus test of all international institutions, especially for the West, the EU, the United States, Canada, Australia. It's about how you will stick to your principles. The very international legal order that grew out of the ashes of World War II is being destroyed in the carnage of Gaza.”

But in such context, he thinks “the prosecutor's office has admirably pushed forward on this investigation, despite those pressures. The prosecutor's office, and the ICC in general, has stood up to those challenges. It's now really a test for other states of their commitment to impartial international justice.” And he thinks that “it is very possible that additional warrants have been issued.”

The Israeli internal front

Rabbani though remains skeptical. “Part of the problem is that for [ICC prosecutor] Karim Khan, history commenced on October 7th [the attack of Hamas in 2023]. And the other issue is, unless there have been multiple major developments which we are unaware of, and which seems extremely unlikely given that it would have been leaked by now: Why have there not been any further applications for arrest warrants given changes of personnel in Israel, given that the Israelis are now much more open and vocal and explicit about their objectives and given that the policies that formed the basis for Khan's initial applications have only intensified in the years since?”

Meanwhile, Diamond points out that “there's a systematic effort to basically silence all kinds of dissenting voices and to remove anyone who can expose wrongdoing by Israel. Palestinian organisations have been facing these kinds of challenges for years. It was very pronounced when five leading civil society organisations were all designated as unlawful organisations or terrorist organisations, including leading human rights organisations like Al-Haq and DCI Palestine, Adamir. With Israeli civil society organisations who are a real headache for the Israeli authorities, the effort now is on a number of fronts. One is to just cut off their sources of funding. And, on top of that – and this is a concern for many of us – Israel is introducing criminal legislation that would make it a crime to support the International Criminal Court.”