“Why me, if I was a doctor, a social leader, a person who provided a service to a community that pleaded for my release, since I was the only one there performing ultrasound scans?” The question asked by Guillermo León Molina, a surgeon who ran the Supía hospital when he was kidnapped in 1998 by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), reverberated through the auditorium of the Eafit University in Medellín, in Central Colombia.

Minutes later, Ovidio Mesa - known as “Anderson” in the rebel group - took responsibility for the crime. “You were kidnapped under my command,” he said, explaining that Molina had been kidnapped because of what he called “crappy information” about his supposed economic solvency. He admitted that they had still charged his family a ransom and that, upon receiving the payment and releasing him after four months in captivity, they had then abducted his 16-year-old daughter Lina María in order to charge them again. “A minor kidnapped, overseen for by armed men, as an object of merchandise in exchange for money,” he said. “It weighs on me that as a commander I never considered the human dimension.”

Martín Cruz Vega, “Rubín Morro” as a FARC member, then told Molina that he knew the town of Supía well. “I know the poverty it embodies, what a bus ticket to Pereira or Manizales costs. It was, as don Guillermo León says, a social damage of the greatest human repercussion,” he said, rattling off the list of irreparable damages caused to the Molina family: the deception that resulted in a second kidnapping lasting two more months, their forced displacement, the suspension of his medical practice, the impotence of a community left without basic healthcare that they paid for even with mangoes and chickens. “We took out our anger on our own neighbours,” he admitted.

This exchange illustrates a new aspect of the kidnapping investigation that has been progressing for five years in the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP), the judicial arm of Colombia’s transitional justice stemming from its 2016 peace agreement, but is not yet visible to most Colombians.

Three years ago, when dozens of kidnapping victims came face to face -and in public- for the first time with former FARC leaders, the latter acknowledged their “savageness” and “levels of inhumanity”. But although they were the ones who had approved and enforced what one indictee called “the damned policy of kidnapping”, they were often unable to answer specific questions from their victims, such as what stories a father told about his child or where to find a relative they never released.

Now, as it is the turn of commanders of regional guerrilla structures - also indicted as having been “most responsible” of these crimes - to face their victims as part of the judicial process, their answers come closer to the suffering and experiences of those they kidnapped or their relatives. After all, they are the ones who gave concrete orders to abduct someone, who held them captive in their units or gave instructions over the radio about the fate that awaited them. There are still many unanswered questions, but this proximity is allowing for dialogues that victims thought impossible until just a few years ago.

“Forty years too late”

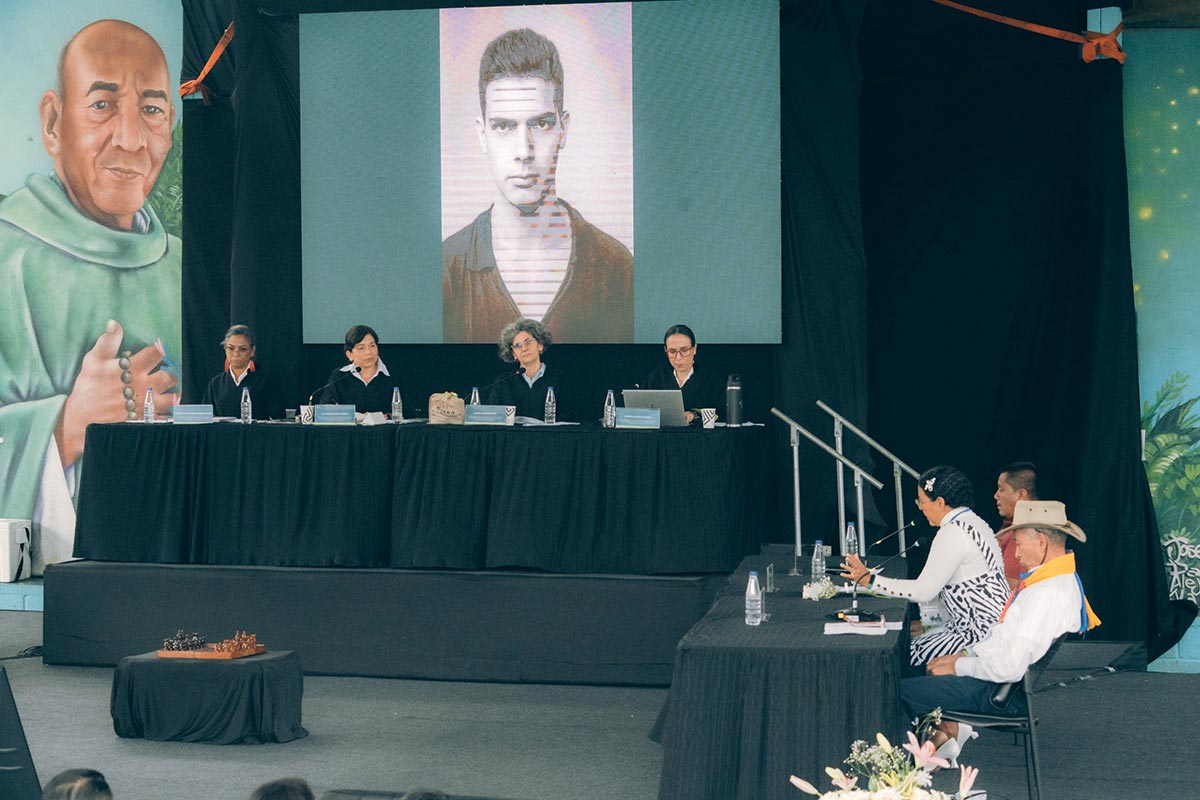

One by one, seven top commanders of the FARC’s north-western bloc, which operated in the rugged mountains of western and central Andes, owned up to their role in a what the JEP termed a war crimes and crimes against humanity. In front of a hundred victims, first in the mountainous village of Caicedo and then in Medellín, they admitted to kidnappings to finance war, force the government to release imprisoned rebels, and assert territorial control. In other words, the three criminal FARC policies identified by presiding Justice Julieta Lemaitre and her team in the macro-case dealing with kidnappings, one of the most emblematic crimes committed during an armed conflict which last over half a century.

“I am guilty of having implemented these policies. I acknowledge all the damage caused to those we kidnapped: the mistreatment, the bad food, the truncated life projects, the many disappeared people who never returned to their homes. How many children were left waiting for their fathers or fathers waiting for their children, how many mothers who had to play the role of father and mother in order to carry their families,” said Rodolfo Restrepo, who was a rebel fighter for four decades under the nom de guerre “Victor Tirado”.

Through both prepared speeches and spontaneous answers, the seven indictees responded to the concerns and petitions of 15 victims. Some did so in a rather mechanical way, as if filling out a checklist of legal obligations: “we committed crimes that cannot be amnestied”, “these were acts of the utmost gravity”, “I want to be emphatic in acknowledging my responsibility by line of command”. Others, like Restrepo, did so looking at their victims in the eyes, owning up to such cruel truths as “we took many poor people, tortured them, made them and their families suffer, only to find out that they had nothing to pay, meaning we either had to disappear or release them”. They spoke truths that are obvious to Colombians, but difficult for former FARC members to voice, such as that these crimes made them lose any legitimacy. As Cruz Vega would say, “I reached this civility 40 years too late”.

Such public hearings are still an unusual scene in Colombia. It is only the fourth time that former FARC leaders or members publicly address their victims to acknowledge their responsibility for at least 21,396 kidnappings committed between 1990 and 2015. Owning up to their crimes is one of the fundamental conditions - along with providing truth and redressing their victims - to receive a more lenient 5-to-8-year sentence in a non-prison setting, rather than a jail term of up to 20 years. The first public hearing took place three years ago in Bogotá, when Rodrigo Londoño or “Timochenko” - the last FARC commander-in-chief - said that “I feel disgust of our actions”. He was followed by ten former commanders of the Central Joint Command in Ibagué in May 2024 and seven commanders of the Western Bloc in Cali last November. Four more FARC regional structures have yet to do so.

“A wound that I carry in my soul and does not heal”

With a mixture of emotion and dignity, the fifteen victims were able to put into words the deepest fears and traumas left by their kidnapping. Luis Honorio Pacheco, a soldier who was held captive for three years, said that not all the letters sent by his relatives were delivered to him and that, two decades later, he still dreams that the FARC are going to kill him. Police officer Máximo Quiroz said that they slept tied up next to minefields, and used the expression “concentration camp” to talk about the physical spaces of captivity that the ex-FARC call “care commissions”.

Indigenous leader Darío Arias Domicó told how rebels accused his father Solangel, governor of the Embera Katío reservation of Alto Sinú, of being a paramilitary collaborator before torturing and murdering him. Ironically, the paramilitaries had also accused him in their case of collaborating with the guerrillas and a year earlier had murdered his brother-in-law, Kimy Pernía. Nicolás Humberto Duque said that his wife had to “negotiate me as one would do for a bag of potatoes, not for the father of our one and three-year-olds”.

Beatriz Carmona recounted the triple tragedy that struck her family in July 1996, when the FARC kidnapped Reinaldo, Daniel and Albeiro Correa, three brothers who worked in a civil construction company in Mutatá. The eldest was 22 years old and the youngest, her partner, had just turned 18. The three men, who were dating three cousins, were weeks away from seeing their children born almost at the same time. Daniel had sown the cloth nappies they would use. “I want to ask you with all the strength of my grief to clarify the location of the place where their bodies were left,” pleaded Beatriz, who has only learned this year that they had been murdered on the day of their abduction.

These pains were all so intense, often private and, so far, little acknowledged by their perpetrators. In the words of policeman Máximo, “in my family we never discuss my kidnapping: it’s, as Diomedes Díaz sang, a wound that I carry in my soul and does not heal”.

Fragmentary truths that emerge

As the case has moved down from the FARC national leadership’s 2021 indictment and 2022 public hearing to charges against its regional commanders, what it has lost in media visibility, it has gained in closeness to the experience of victims at the local level.

Cruz Vega asked to speak in order to acknowledge that he ordered the kidnapping of truck drivers like Luis Eduardo Flórez to force them to carry armed rebels and weapons in their lorries. “I acknowledge today that we forced them to do forced labour against their will and that this should have not happened. This brought them stigmatisation, because people started saying that they were collaborators of the guerrilla. I own up to the fact that I ordered it,” he said.

There were Mea Culpas about kidnappings whose direct victims were not present, such as the famous case of police corporal José Norberto Pérez. The FARC held him hostage despite public pleas for clemency made by Andrés Felipe, his 12-year-old son who suffered from terminal cancer. He died without any response to his pleas and, three months later, the FARC murdered his father. At the beginning of the hearing, several former rebel leaders justified themselves by saying that they had raised his case with their superiors but that “Iván Márquez” - the rebels’ chief negotiator in Havana who ended up abandoning the peace deal and taking up arms again - ordered not to release him. With more self-criticism, Jesús Mario Arenas – also known as “Marcos Urbano” - acknowledged that “we did not make a great effort to insist that he could leave, we carry that on us”. After a pause, he added: “those immovable beliefs in war are what lead to tragedies”.

The setting of the first day of the hearing was highly symbolic. Not only was it the first hearing held in a small municipality ravaged by war and now known for its culture of non-violence, but it was where the FARC kidnapped state governor Guillermo Gaviria and his peace advisor, former defence minister Gilberto Echeverri, in 2002. The two men had come to the small bridge at the entrance of town as part of a peaceful march demanding that guerrillas allow peasants to use the road connecting the town with the rest of the country to sell their speciality coffee. After a year in captivity, the FARC killed them both along with eight soldiers.

“The mark of sexual violence haunts us”

In these regional hearings, local commanders are acknowledging behaviours they had previously minimised. First they’re admitting to torture and cruel treatment of abductees and the suffering of their families. More recently, including in the Caicedo coliseum with the painted faces of Gaviria and Echeverri as a backdrop, they’re starting to admit unequivocally that many victims suffered sexual violence in captivity.

Rolando Chica recounted the guerrilla takeover of the rural hamlet in Puerto Libertador where he was a policeman in 2006 and how it meant, in his words, “the destruction of my life”. “Look at all the pain I’ve had to live through”, he told them, before telling them, in a cracked voice, that he was raped on several occasions, only to be stigmatised for it in the public institution where he worked and from which he was removed without further explanation.

Ángela Damaris Díaz recounted a 24-hour ordeal in which she was raped by at least three men, simply because she had mothered a child with a policeman in her village of Argelia. “I kept silent for more than 20 years. I didn’t want anyone to know, I was too ashamed. I spent those 20 years in solitude, overprotecting my daughter so that what happened to me wouldn’t happen to her”, she told them.

Although many former FARC members continue to insist that sexual violence was forbidden in the guerrilla and that those who committed it were executed, today they admit more clearly that it did happen. “For me, it’s difficult to accept rape because I joined the rebels in search of an ideal, but the war transformed us. I am ashamed that our men, militiamen or guerrillas, committed this in Argelia, a village where we had total control,” Jesús Mario Arenas told her. “That mark haunts us.”

“We let you off quite quickly”

Despite such breakthroughs, there were also moments when the indictees did not seem to understand the magnitude of the suffering they had caused.

With the gestures of an orator, almost as if he had been preparing this moment all his life, prosecutor Milton Rodríguez recounted how he was kidnapped while driving to the town of Cañasgordas to investigate a feminicide. He was chosen at random at an illegal checkpoint, what the FARC called “miraculous fishing expeditions”, but when they realised he was a public official, they decided to keep him to force a swap. He was held captive for a month and lived for years in fear because of his decision, out of personal ethics, not to comply with the order to take a message to the media. This fear led him not to take up a position he won in a public competition, because he feared he would be assigned to a town under rebel control.

“I want you to acknowledge that my kidnapping took place because I was a prosecutor and a public servant, that you affected the administration of justice in that territory, that you stole the computer with the case I was handling,” he told them, stressing that he was a humble professional who had worked hard to graduate from university. Visibly upset, he also denied a version maintained by one of the accused, according to which he had been kidnapped because of a decision he had taken as a judge in Urabá to release a group of rebels who were later killed by the paramilitaries.

Yoverman Sánchez, formerly “Manteco”, began by owning up to his role in Milton’s kidnapping. “I am the main responsible for your kidnapping, because it was carried out by my number two. I acknowledge that we put an end to your peace of mind, that we affected your professional career and damaged your family life,” he said. But he then added that he “cannot acknowledge” that prosecutor Rodriguez had been declared a military target, even though he could imagine his fear. After a surreal soliloquy about how justice operators in Colombia re-victimise many victims and a counter-question from justice Marcela Giraldo about their victim’s denial of having ever been a judge, Sánchez said it was not true. “But Milton, you did work in Turbo [a town in the Uraba region] in 1997”, he barked at him, leaving the false accusation up in the air. He then told him: “we let you off quite quickly”, as if the suffering of a kidnapping victim could only be measured in years and not in months.

A chess set and a wooden box

In the midst of so much pain, there was also room for catharsis. Sergeant Heriberto Aranguren recounted how he was locked up with four other soldiers for two years in what he described as a “wooden box” measuring three square metres. A space so cramped, he explained, that it created very difficult conditions of hygiene and of coexistence, until all his fellow captives were released and he was not because of his rank.

His intimate strategy of resilience at that time, but also later on when he was taken to the group of state governor Gaviria and former minister Echeverri, was to carve chess sets. He created more than a hundred. One of them, its shiny brown pieces made of chonta wood, was there in the space between him and the seven indictees he was addressing, autographed by his murdered kidnapping companions.

“That day when I was left alone, I kept asking, why, my God, why? It wasn’t why, but rather what for. And that reason is to be here today telling all of you what happened to me.”