In October, the Stockholm District Court entered a new phase in Sweden’s longest criminal trial. The hearings in the Lundin trial – where two former senior executives of a Swedish oil company are charged with complicity in war crimes committed in Sudan – turned to a group of men who once controlled access, checkpoints, and security in Sudan’s oilfields — the security advisers hired by Lundin Oil. They were there, they wrote the reports, they saw the bodies being buried. Yet twenty-five years later, on the witness stand in Courtroom 34, they remember almost nothing.

After twenty-two years in the British army — with deployments in Northern Ireland, Cyprus and the former Yugoslavia — Richard Ramsey was not ready to retire from the world’s conflict zones. One day, reading a veterans’ magazine, he noticed an advertisement: “Security expert needed in Sudan.” That job would lead him not only to oil Block 5A in southern Sudan but, a quarter of a century later, to a stone bench outside a courtroom in Stockholm. “As a former soldier, I’m good at waiting,” Ramsey says as the green light above the heavy oak door remains dark. On Mondays, the court often struggles with technical issues. Around thirty lawyers, prosecutors and defence teams must log in and connect the accused — Ian Lundin and Alex Schneiter — who follow the trial remotely from Geneva.

After more than two years of proceedings, the process has now reached the stage where about ten former security consultants are being heard. Among them is Ramsey.

When the protectors themselves attack

The prosecution’s case rests heavily on internal security reports that, they argue, show how the Sudanese army and allied militias began a military campaign in May 1999 to secure control over Block 5A – the oil exploration area of Lundin – and enable oil operations. Those documents were discovered when Swedish police, on a January 2018 morning, raided Lundin’s Stockholm headquarters. At the same time, Swiss investigators searched the company’s Geneva office and the Lundin brothers’ private premises. According to the prosecution, the documents prove that Lundin requested “security” in areas not under government control. That detail is crucial: it is not illegal to cooperate with a military dictatorship — even during a civil war — nor to request protection from a state army against rebels. What matters, prosecutors say, is that Lundin understood the consequences of asking the army to “secure” its operations.

Ramsey wrote several of those security reports and received many more. The first document presented to the court describes growing concern in December 1998 that the Sudanese army might enter Block 5A. “If the army crossed the river to take over the block, they would face resistance,” Ramsey recalls when asked in court.

At that time, the company’s protection was handled not by the army but by two local militias: Paulino Matip’s South Sudan United Movement (SSUM) and Tito Biel’s South Sudan Independent Movement (SSIM). This arrangement, Ramsey explains, was based on the 1997 Khartoum Peace Agreement, “which was very important” as the company claimed it gave it the conditions to operate.

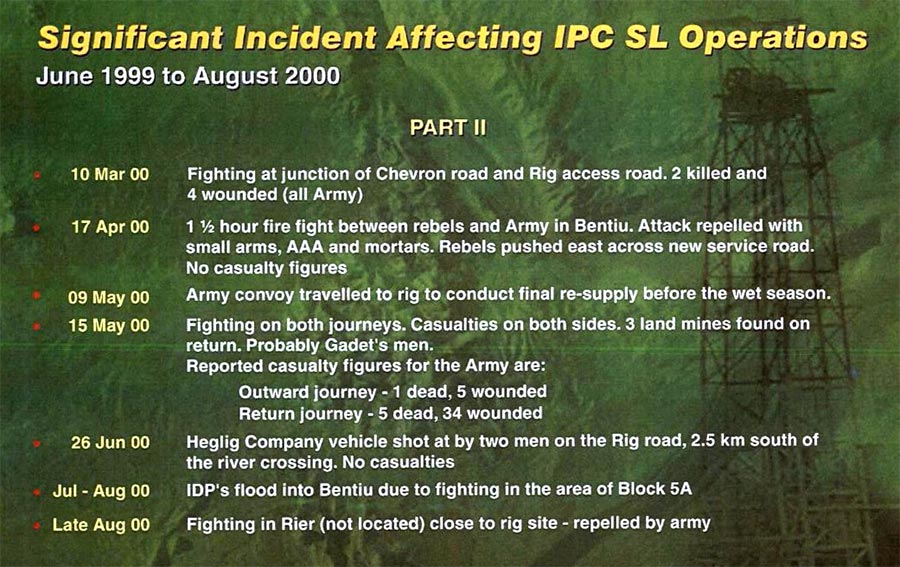

Whether the army entered Block 5A before or after oil was found remains disputed. But 1999 internal reports show that 300 SSUM soldiers under Matip moved south toward the Thar Yath rig, along a newly built road, accompanied by trucks loaded with machine guns. On courtroom screens, prosecutors display a map marking where guards employed by Lundin Oil were captured, bodies found, and gunfire broke the silence on May 3, 1999. Two guards were killed instantly; two others fatally wounded.

In the analysis section of that report, the conclusion reads: “The security arrangement based on local militias and police has failed.” The recommendation: responsibility must now shift to the regular army.

A 50-kilometre “buffer zone”

That, prosecutors argue, was the turning point — when oil operations in Block 5A became dependent on military offensives.

“Reading this, does anything come back to you — what triggered those events?” prosecutor Henrik Attorps asks.

“No, it’s like reading it for the first time,” Ramsey replies.

He was in London when the Lundin rig was attacked and several security staff were killed.

When news reached him, he recalls thinking that “the rumours had come true — the guard force had imploded”. Those meant to protect the rig had instead attacked it. A few days later he was back in Sudan, helping his colleague Dick Deary write a security plan and an incident report. He also met company founder Adolf Lundin soon after.

The rig attack has become a central moment in the prosecution’s timeline. It coincides with what the indictment labels “assistance act 9a” — May 1999 — when Ian Lundin, Adolf’s son who was now the company’s chairman, allegedly demanded that the Sudanese army establish a 50-kilometre “security zone” around the rig and installations, triggering a series of military operations. That internal document, later seized by police, shows the company requesting “full military control within a 50-kilometre radius”. Prosecutor Attorps highlights that the company still planned to build new roads into areas it described as “hostile”, such as the Jikany region.

“Can you explain how the company went from emphasising peaceful conditions to planning roads through hostile territory?” Attorps asks.

“Before the incident, operations were possible — chaotic but doable,” Ramsey says. “When supposedly friendly forces come to your rig, kill people, loot and murder, something changes. We could no longer rely on the hybrid militias. We needed a reliable force — and the army seemed to be one.”

“I can’t explain that”

Did anyone inside the company discuss the civilian impact of this militarisation? “I don’t recall any such discussions,” Ramsey says. “I don’t remember any assessments beyond a general sense that things were tense.”

Prosecutors then display another report noting that the World Food Programme had recorded 5.000 displaced people arriving from Leer, Duar and Koch to receive food aid. Villages within block 5A. Ramsey says he has no recollection of such information.

“By early June, reports speak of thousands fleeing the fighting in Western Upper Nile,” says Attorps. “Even without reading reports, were you aware of displaced civilians from your areas of operation?”

“I don’t recall any information like that,” Ramsey answers. “Maybe I knew something then, but not now.”

In another report cited by the prosecution, dated 25 October 1999, Ramsey had written that “the army is pushing hard into the area” and that a planned field visit was cancelled due to insecurity.

“What did you mean by ‘pushing hard’?” asks the prosecutor.

“I can’t explain that,” Ramsey says flatly.

Another “Weekly Report,” authored by Ramsey on 24 November 1999, noted that while the army could hold the town of Rubkona and the rig, “the road to the rig remains the most dangerous stretch.” The report also stated that the army lacked control in Block 5A during the initial stages of road construction, and that the company had therefore requested further military assistance. “I don’t remember this specific report,” Ramsey says, “but I do recall that the army rarely had the resources to spare.” Asked how the company could continue road construction in such conditions, he again says: “I can’t remember.”

When prosecutors press him on what “substantial operations” meant, he explains that it probably referred to the number of troops needed to secure the project. “A few battalions would have been necessary,” he says. “Each battalion — 600 to 1000 men. So yes, perhaps a few thousand soldiers in Block 5A that autumn.”

More attacks, more soldiers, more deaths

On 28 February 2000, the army clashed with rebels in Rubkona. The block was evacuated; the situation rated “black.” The next day, rebels attacked the road-building crew ten kilometres south of Rubkona. Thirteen people were killed.

“I remember that day very well,” says Ramsey. “Tension was high from previous fighting. When we heard gunfire south of the river, I went to the bridgehead with the company doctor.” Later, he saw soldiers burying bodies in a pit — men killed in the ambush. The company’s incident log noted that the army was “trying to bring in reinforcements” and that all operations were being evacuated. “It was extremely tense,” Ramsey recalls. “Completely impossible to continue work under those conditions.”

Subsequent logs describe more attacks, further deaths, and reinforcements arriving with armour. By mid-March 2000, 500 additional troops were reportedly in Rubkona. Rebel commander Tito Biel was said to have 4.000 men near Bentiu; SPLA-allied forces were joining him. The army, according to one note, began setting fires south of Bentiu “to burn the rebels out.” “I don’t recall those specific events,” Ramsey says. “But I remember seeing fires in that direction.”

What report?

For prosecutors, the issue is threefold: that war crimes occurred; that the accused knew about them; and that their actions enabled those crimes.

To demonstrate knowledge, they present minutes and briefing papers showing how the company’s security advisers at following meetings listed the “pros and cons” of the situation. On the “pro” side: an army division moved to Rubkona, checkpoints were established, and an alliance against rebel leader Peter Gadet, an ally of the SPLA, had formed. On the “con” side: Gadet remained active, and there were no security guarantees.

In a report dated 18 January 2001, Ramsey summarised the army’s deployment along the rig road and around the large villages of Adok and Leer: one battalion (about 600 men) in Rubkona, two companies (a company is up to 250 men) in Bentiu, and two-three companies along the road and at the rig. “Peter Gadet was the main threat, so we needed forces there,” Ramsey comments in court. But when Christian Aid published its 2001 report “Scorched Earth”, accusing government and militia forces of crimes against civilians in Block 5A, Ramsey says he never heard of it. “I knew civilians were fleeing,” he admits. “We had displaced people arriving at our base in Rubkona and at the rig. But the report? No.”

Yet prosecutors then display an internal memo Ramsey himself had written on 7 April 2001 — titled “Rebuttal of Christian Aid Allegations.”

“Nice one, bravo,” Ramsey says with a smile, prompting laughter in the courtroom, before insisting he did not remember writing it.

Reading from Christian Aid’s account of villages attacked along the oil road, 11.000 people displaced, and settlements burned, prosecutor Attorps asks:

“Do you have any recollection of these allegations?”

“No,” Ramsey says. “I recognise the village names, but not the incidents.”

The “buffer zone” concept

The following week, another former security adviser takes the stand. John Davidsson is a former British special-forces soldier who later worked for the private firm Rapport Ltd to analyse security in Block 5A. “A buffer zone,” he explains, “is a military concept. When protecting an operation, you create concentric rings — layers of early warning so you’re not surprised.” Those “rings,” he says, could include villages, civilians or local informants — not just soldiers.

In his “Security Survey Report: Lundin Sudan Ltd Operations in Khartoum and Southern Sudan” (Novembre 2001), Davidsson warned that rebel leader Gadet was targeting oil infrastructure. The report identified Thar Yath and Kwosh as vulnerable to mortar attacks from 7–10 kilometres away and recommended building a new road westward to create a protective “buffer.”

“Gadet had 120-millimetre mortars,” Davidsson says. “They’re not precision weapons. They can fly ten kilometres and scatter shrapnel over 100 metres. A road could push the army far enough west to shield the rig.”

“So the company built the road for the army — to create that buffer?” the prosecutor asks.

“Exactly.”

“Did it make the area safer?”

“It made troop transport and evacuation easier. Vital for evacuation, yes.”

“If the road hadn’t existed, could the army still have protected operations?”

“I have no idea,” Davidsson replies.

Opportunities for the defence

The defence seizes on the witnesses’ fading memories. If these men, who lived for years in Block 5A during the alleged crime period, saw no evidence of atrocities, then, the lawyers argued, how could Lundin’s executives have known?

When cross-examined, Ramsey is asked directly:

“Did you ever see burned villages?”

“No.”

“Did you ever hear reports of such things?”

“No.”

Defence counsel Thomas Tendorf then refers to Ramsey’s earlier testimony that civilians had fled to the company’s compounds in Rubkona and Thar Yath.

“Those places were heavily guarded by army troops, correct?”

“Yes,” Ramsey says.

“So the civilians sought refuge where the army was. That means they fled from the SPLA rebels — not from the army.”

Defence lawyers also point to internal reports using the term “cordon” to mean securing an area “to keep small bands of bandits away from operations.” Where the prosecutors spoke of “army guards,” the defence describes a “guard force.”

“Did you ever see or hear of the guards killing or abusing civilians?”

“Never,” Ramsey answers.

As the weeks of testimony continued, the courtroom rhythm slowed. The prosecutors sought details; the defence emphasised doubt. The witnesses — old soldiers turned oil-company contractors — often fell back on the same phrase: “I don’t remember.”

For the prosecution, this collective amnesia underlines the distance between the documents and the people who wrote them. For the defence, it reinforces the idea that these men — and by extension Lundin’s leadership — neither ordered nor where behind any military campaign.

“Could the company go to the army and say, ‘We want a military operation here or there?’” defence lawyer Tendorf asks.

“No,” Ramsey replies.

“Did you ever try?”

“No. I had no interest in demanding offensives, and I don’t think the army would have been interested either.”

“As a former British officer, would a national army let a private company influence its operations?”

“Absolutely not. They have their own plans and routines.”

“When clashes broke out, what did Lundin Oil do?”

“We immediately shut down operations,” Ramsey says. “We evacuated until the fighting stopped and peace had been negotiated.”

The “kind of people” you are dealing with

The Swedish prosecutors are not trying to prove that Lundin itself committed atrocities but that the company’s pursuit of oil aided the army’s campaign of forcible displacement in Block 5A between 1999 and 2003. To do so, they must show that the executives knew what the army was doing, and that their requests for “security” amounted to assistance in a war crime. Yet the witnesses called to clarify those crucial years describe events as if they happened to someone else, somewhere else. They acknowledge smoke, gunfire, rumours — but not orders, not intent. When prosecutors read from the Christian Aid report describing entire villages cleared along the oil road Ramsey’s response remains the same: “I recognise the names, but not the incidents.”

The same pattern echoed in other testimonies. Mark Reading, Talisman’s former head of security, describes seeing tracer fire over Khartoum one night in 2000, reporting it, then being summoned by an enraged Sudanese security chief who denied any fighting had occurred. “That’s when I realised what kind of people I was dealing with,” Reading tells the court. When asked whether he knew what the SPLA rebels thought about oil extraction, Reading says simply: “I don’t know what they thought.”

“Did SPLA approve of oil operations?”

“No idea. But if you ask whether SPLA-aligned rebels attacked oil infrastructure — yes, they did.”

“Why?”

“Wars in Africa — in any country — tend to be about resources. If you lack them, you try to correct that imbalance.”

As the hearings of the former security chiefs draw to a close, the prosecution has built its case not on the men’s recollections but on the paper trail they left behind: weekly situation reports, security analyses, letters to Khartoum. In December the court will hear Ken Barker, the main security chief during the period and the man behind most of the most crucial reports.