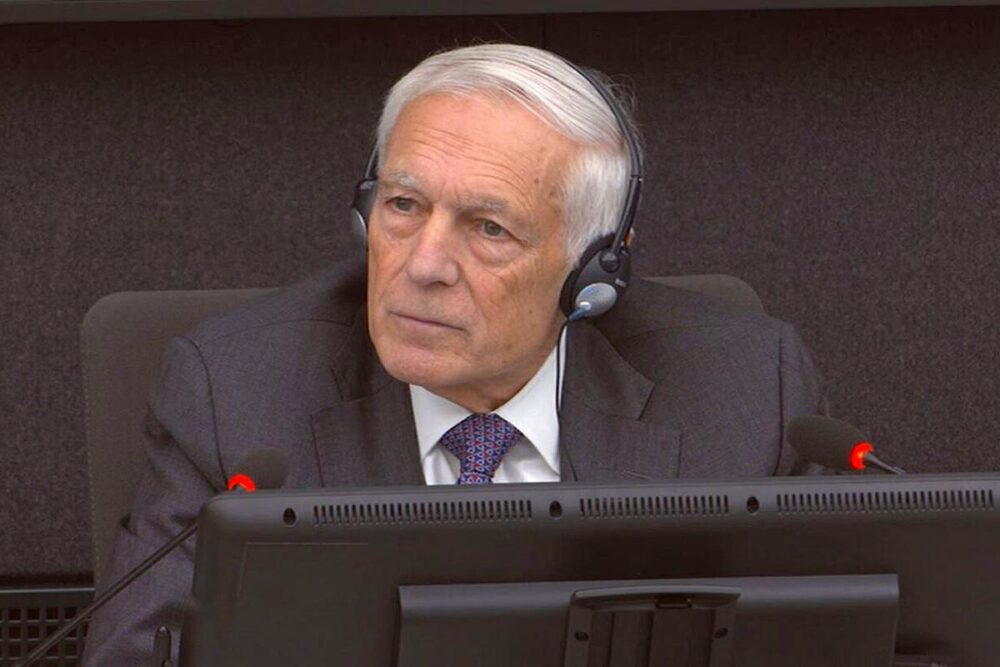

All four accused looked attentively at Wesley Clark as he took the witness stand on November 17 before the Kosovo Specialist Chambers, a Hague-based international tribunal trying former leaders of the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), including former Kosovo president Hashim Thaçi. The 80-year-old American former general served as NATO Supreme Allied Commander for Europe from 1997 to 2000. Dressed in a dark suit, Clark kept a calm half smile throughout the two days of hearings. He told the judges that Thaçi “was the spokesman, he was clean cut. He didn't look like he'd been out in the woods fighting for a year or two. And it was pretty clear that he wasn't in charge”.

Hashim Thaçi, Kadri Veseli, Rexhep Selimi and Jakup Krasniqi are accused of ten counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity, including torture, illegal detention and persecution. They were all high-ranking figures of the KLA who went on to become prominent Kosovo politicians. According to the prosecution, the KLA had a well-structured chain of command, and the accused bear individual and command responsibility for the charges, which also cover the murders of more than 100 people from at least March 1998 through September 1999 in multiple locations across Kosovo and in northern Albania. 155 victims are currently taking part in the case as civil parties.

The alleged crimes are in the context of the 1998-99 ethnic Albanian uprising against the Serbian forces, who ruled over Kosovo. The Serbs were eventually forced out by a 78-day NATO air campaign, called Operation Allied Force, that hit the Serbian part of the former Yugoslavia and lasted from March to June 1999. On June 10, Serbia signed a ceasefire and military withdrawal agreement with NATO. Two days later, the NATO peacekeeping force KFOR was deployed in Kosovo. Leading it was British General Mike Jackson, who demanded that the KLA give up their arms.

Clark conducted the NATO air campaign and oversaw the subsequent demilitarisation of the KLA. “It wasn't an organised military”, he told the court. “These were regional, localised groups of fighters who sort of banded together to protect their communities. My assumption was that after NATO got in, these people actually got to meet each other, got to talk, but there was no real submission to authority.”

The killing of the Jashari family

The trial opened in April 2023. Over two years, the prosecution presented 125 witnesses and another 137 statements in writing. After that, the court heard 2 expert witnesses from the victim’s lawyers. On September 15, the Thaçi defence started presenting its case with the testimony of former US diplomat James Rubin. Its seven witnesses were US, UK, NATO or UN officials at the time of the Kosovo war. Clark is the last one.

Around 60 people filled the public gallery on the first day of Clark’s testimony. Besides some Kosovan journalists, the majority were Kosovo politicians and relatives of the accused. They greeted each other as they walked into the Court. When the curtains lifted on the courtroom, the four accused waved and smiled at them.

Thaçi's defence lawyer Luka Mišetić asked Clark how he saw the KLA at the start of the war. “There wasn't much really to talk about in terms of structure. As far as we knew, these were local groups that had emerged more or less spontaneously in response to years of Serb oppression. Especially after the murder of the Jashari family, I think there was a genuine alarm that more was coming,” Clark responded.

The killing of the Jashari family marked a pivotal moment in the conflict. Violence between ethnic Albanians and Serb forces had intensified since early 1998. On March 5, the Serbs attacked the home compound of KLA commander Adem Jashari in the village of Prekaz, about 40km North-West of Pristina, Kosovo’s capital city. More than 50 people were killed, including Jashari and most of his family. This led more ethnic Albanians to join the KLA, and group members in the diaspora to return to Kosovo.

“He had no idea what was going on”

In a statement made to the defence prior to the hearing, Clark said that it would be “unjust to attribute the misconduct of others to Mr Thaçi”. Clark testified that he first met Thaçi in the backdrop of the failed 1999 peace agreements with Serbia, which the general did not attend directly. Thaçi was then the spokesperson of the Kosovo delegation. They met once again around the start of the air campaign, Clark said. “He was just one of the people there”, he paused. “He was the most presentable. He was the youngest, had a better haircut, better clothes. But he wasn't a military commander.”

As NATO tried to put pressure on the president of Serbia Slobodan Milošević, Clark told the Court that he sought the KLA's support to localise Serbian targets in Kosovo. He met with Thaçi, but “we never got any help, he had no idea what was going on”. The general recalled showing the accused a map of the region, “I was asking him, where are you? Where are they? What should I strike? Nothing”, said Clark, moving his hand across in the air and shaking his head.

Mišetić asked whether NATO used the KLA “as a form of troops on the ground”. Clark said that they tried. “I wanted forward observers so we could strike and not make mistakes.” He said that one time NATO hit a building surrounded by Serb vehicles, thinking it was one of their headquarters, and later found out that it had killed around 80 civilians, detained and encircled there by the Serbs. “That was an example of the fact that we couldn't get any information off the ground.”

“Did you have an assessment of whether there was any civilian control over the KLA?” asked Mišetić.

“No, there was not.”

“Would it have been possible for the KLA to have a functioning chain of command from the top to the bottom without NATO and the United States knowing it?”

“No, no,” Clark half laughed.

“We didn't have that information”

On June 10 1999, the NATO-led KFOR entered the area. Around ten days later, following KFOR's pressing demands, the KLA agreed to demilitarise and cease all hostilities. However, according to the indictment, “FRY [Federal Republic of Yugoslavia] and KLA forces violated the terms of international resolutions and agreements through the summer of 1999, continuing hostile and provocative acts”. And it was only on September 20 that the KLA gave up their weapons.

“I'm aware that there was a series of confrontations during this period. But I never thought it was KLA,” Clark told the Court. “The resentments and the fear were so deep that this kind of spontaneous violence was almost inevitable.” In the summer of 1999, NATO was trying to stop the ethnic violence, said Clark. “Believe me, if we had had information that it was organised by the KLA, we would have put our foot down really hard on it. We didn't have that information.”

When asked about KFOR's struggle to convince the KLA to respect the demilitarisation order, the witness said that “these people were still like, ‘I risked my neck on this, you're not going to tell me what to do easily’. They were subjected to systematic ethnic repression for a period of more than a decade, where the Albanian language wasn't accepted in schools and so forth. These men who fought back, they were pretty independent-minded”.

How much did Clark know?

During the four hours of cross-examination, prosecutor Matthew Halling asked Clark about the level of organisation within the KLA. During a September 1997 event detailed in a KLA communique, “by decision of the central staff, the KLA armed units carried out a synchronised operation”, attacking 12 police stations, said the prosecutor. Clark laid back on the chair and said that he did not remember seeing anything like this.

Halling went on to read from the book Kosovo Liberation Army: The Inside Story of an Insurgency, where author Henry H. Perritt describes the group’s “strategic goals and objectives”. He asked whether Clark knew about these goals. Clark said that he wasn’t aware of them, but that he “never assumed that the KLA had no strategy or no intent”. He added that it “is not necessarily an indication that they have effective command and control”.

In another page in Perritt’s book, Thaçi is described as a political figure but also a fighter, and there is a picture of him holding a weapon next to Adem Jashari. “Have you ever seen that picture?” asked the prosecutor. Clark said he hadn’t.

“You actually don't know if Hashim Thaçi fought or not. You only know that people told you he was a political leader, correct?”

“That's correct.”

An articulate, presentable and ambitious man

The next day, Halling questioned Clark on the scope of the information sharing from the KLA during the air campaign. Among other sources, the prosecutor read from the 2002 report Disjointed War, prepared by the research organisation Rand for the US Army. “During May [1999], reports from the KLA became an important source of intelligence and targeting information for Task Force Hawk”. That was the task force that Clark created to support the NATO campaign. “General, this is yet another indication that this information from the KLA was getting to you, wasn't it?”. Clark replied quickly that they did try and get as much intelligence as they could, “but trying to extract information from a force like the KLA was a lot different than having an allied force that had a structure, radios, reporting and all that stuff”.

“I put it to you that you don't know enough about what the KLA was doing throughout the war to know if the charges he [Thaçi] faces in this court stand or not. What do you say to that?” concluded Halling.

“From my experience with it and what I saw, he was not effectively acting as a commander in chief, in which everybody obeyed his orders. All of the impressions that I had at the time, this was a group of people who came together over a period of time to try to defend their population against Serb ethnic cleansing. Thaçi just happened to be the most articulate and presentable of the people, and he was an ambitious man from the start. And he worked his way up. But to have control? No way that I could see.”

Clark’s testimony marked the end of the hearings in the defence case. Thaçi’s defence team requested to include one more written statement. All other previously scheduled witnesses were cancelled, including those from Krasniqi’s team. Defence lawyers for Veseli and Selimi announced in July that they did not intend to present any evidence. The panel of three judges, presided by Charles Smith, plans to end the phase where evidence can be admitted in early December. Closing statements are scheduled for February 2026.