On Monday, September 15, former US official James Rubin told the Kosovo Specialist Chambers in The Hague that former Kosovo President Hashim Thaçi was “a public face” to present to the West and “was not in charge” of the armed group that took part in the 1998-1999 war in Kosovo. Rubin was the first defence witness in the trial of Thaçi and three other former members of the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

All the accused were present in the courtroom and gazed up towards the public gallery as the curtain rose on this new phase of the trial. They smiled and nodded at their family members and friends, some of them Kosovo politicians, who flew from Pristina to attend the hearings. Around 60 people filled the gallery, among them the Kosovo and Albania ambassadors. A few dozen Kosovar journalists gathered outside the Court gate in the blowing Dutch morning wind to stream the first live updates to their national media, before stepping inside.

Thaçi is tried as a high-ranking figure of the KLA during the Kosovo war to gain independence from Serbia. The other three accused were also former high-level KLA members who later became key figures in Kosovo politics, Kadri Veseli, Rexhep Selimi and Jakup Krasniqi. They have been in custody since November 2020. The four accused have pleaded not guilty to all charges. The case opened in April 2023 and has so far seen 127 witnesses testifying live in court, many of them behind closed doors, and another 137 witnesses' statements admitted in writing. The prosecution case closed in April 2025. 155 victims are currently taking part in the case, and 2 expert witnesses testified in the victims’ case in July, on top of the 125 who had come for the prosecution.

On the Sunday before the start of the defence hearings, hundreds of ethnic Albanians from Kosovo and several European countries organised a demonstration in The Hague. They waved KLA (or UÇK, from the Albanian Ushtria Çlirimtare e Kosovës) flags, framing the black Albanian eagle on the red background, to protest against the court and what they perceive as an unfair trial.

The young Rubin meets the young Thaçi

According to the prosecution, the KLA had a well-structured chain of command, and the accused bear individual and command responsibility for crimes against humanity and war crimes. These include illegal detention, torture, and the murders of more than 100 people from at least March 1998 through September 1999 in multiple locations across Kosovo and in northern Albania. The alleged crimes are in the context of a war where the ethnic Albanian Kosovar of the KLA fought Serbian and former Yugoslav forces, holding power in Kosovo at the time. Serbian forces were eventually forced out of Kosovo by a 78-day NATO air campaign from March to June 1999.

The events recalled by Thaçi’s lawyer Luka Mišetić centre around two main events that framed the NATO bombing. From 1997 to 2000, James Rubin was the assistant secretary of state for public affairs and chief spokesman for the US State Department. He was considered Secretary Madeleine Albright's right-hand man during the Clinton administration. As such, he attended with her the peace talks between Albanian Kosovars and Serbs in Rambouillet, France, in February 1999 and later was a special negotiator at talks to demobilise the KLA in June that year.

It was in France, Rubin recalled, that he first heard about and met Thaçi. Just 30 at the time, Thaçi had been chosen as the chairperson of the Kosovo Albanian delegation. “We were unaware of the KLA in general. It was very small and in our minds, not a well-understood or very significant force,” said Rubin to the three-judge panel presided by Charles Smith. Albright tasked Rubin with getting to know Thaçi, since he would be instrumental in signing the peace agreement, and so they spent a lot of time together, the witness said.

Helping the peace process

The talks initially broke off in February 1999, as NATO leaders were not ready to include the demands for independence that were key to some of the KLA leaders. During the hearing, part of Rubin’s statement to the defence was read, where the former US official stated that “at some point during the conference, Mr. Thaçi shared with me his worries that he did not have full authority to sign on behalf of the KLA without approval. This is when I started to realise that he was more of a public face for the KLA to present to the West and that he was not in charge. Frankly, we were not sure who Thaçi needed to get approval from. Some thought it was Adem Demaçi [imprisoned for 28 years in former Yugoslavia for his passionate advocacy of Kosovo Albanian rights, later becoming a symbol of the national independence struggle; he died in 2018]. All we knew was that it was the military that had to make the decision”. When Thaçi’s lawyer Mišetić put this statement to Rubin, the witness replied that it was clear to him that Thaçi could not dictate anything, “but rather he could reflect decisions made by that amorphous thing called the Kosovo Albanian leadership”.

After a few weeks, the talks resumed. Rubin recalled that the majority of the KLA decided to side with NATO, and the extremists were sidelined. Krasniqi’s lawyer, Venkateswari Alagendra, turned the attention on her client later in the hearings. “Having the opportunity to engage with Mr. Thaçi and the Kosovo delegation, do you agree with me that you saw nothing in the body language, conversations or interactions that suggested Krasniqi, the spokesperson, was anything other than a supporting voice of moderation who was trying to help Mr. Thaçi and those in Rambouillet with the help of the US to end the conflict?” Rubin replied: “That seems like a fair assessment to me.”

Looking up to America

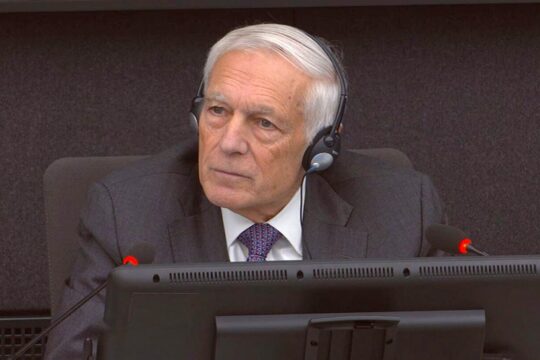

The Kosovo Albanians finally signed the Rambouillet agreement on March 18, 1999, but the refusal to sign from the Yugoslav and Serbs meant the beginning of the NATO air bombing of the Serbian part of former Yugoslavia. Only on June 10 an agreement was reached for the withdrawal of the Yugoslav and Serb armies from Kosovo. The new NATO-led international peacekeeping force, KFOR, arrived in Kosovo under the command of British General Mike Jackson. He wanted the KLA to give up their arms, and Rubin was sent to join the negotiation for demilitarisation. For three days, he recalled meeting Thaçi and “the actual KLA commanders” in their mountain hideaway location. “They were older men in their 50s or above. Hashim was a young man, like me in that picture [shown by the defence, Thaçi and Rubin sit on a brown couch], looking awfully young. And so it was clear to me that he was not in charge. He didn't have the knowledge, the capabilities, or the authority to make decisions in any way, shape, or form. [...]They told him what to do. He didn't tell them what to do.”

In exchange for signing the demilitarisation, Rubin offered Thaçi a call with US President Clinton. The young Kosovar went on to become the first Prime Minister of the country, after it gained independence from Serbia in 2008, a move recognised by the US and many other Western nations, but not by Belgrade. Thaçi always enjoyed support from the US administrations, regardless of their political colours. “What was your understanding of the value that Mr. Thaçi has placed on his relationship with the United States?” asked Mišetić. “From the moment I met him till the last time I met him [in 2020], I felt that America for him was a symbol and a substantive reflection of what he considered powerful, good leadership,” said Rubin, joining his hands and smiling. “He wanted the support of the US, that was, to my mind, his highest priority beyond his own respect and interest in protecting his own people.”

The side of the angels

Rubin said that over those years, they repeatedly received claims that the KLA was committing executions and other crimes. “We had lawyers, we had intelligence officials, we had experts on international crime and legal advisors' office, the war crimes unit,” all looking at whether there was substance to those claims. Rubin said that they did not find evidence that these crimes were being ordered by the leaders of the KLA, and he concluded that the claims were “largely false and designed to undermine our support for the people we were proud to have helped prevent from being slaughtered”.

Replying to Veseli’s lawyer, Rodney Dixon, Rubin added: “After Bosnia, where we felt we stopped a war, we were proud of that and we saw a new situation arriving with Kosovo. And again, we wanted to be sure we were, as we put it in government, on the side of the angels. That's what we would say to each other, that we were for the victims. And they wouldn't be victims if they were committing war crimes…”

The witness said that during 1998 and 1999, each morning he would read “all relevant media reports, as well as intelligence reports and diplomatic cables from our embassies and missions”. Rubin said they would have gone “to extraordinary length” to make sure they were not on the side of someone committing such crimes and that it “would have been a real blow to us if there were some real substance to those charges. They were the victims not only of decades of oppression, but now were being slaughtered in large numbers by Serbian paramilitary and military forces.”

Before and beyond angels

There was an immediate change in atmosphere when the Prosecution started his cross-examination on Monday afternoon. Rubin’s long answers were cut short by prosecution lawyer James Pace, who asked him to say yes or no whenever he could. Pace first challenged the fact that Rubin did not know Thaçi before Rambouillet, presenting news items and other US officials’ reports mentioning the accused, that Rubin said he was not aware of. One of them was a BBC report dated August 1998 and titled “Kosovo Liberation Army Names Political Representatives”. Two of them were the men now sitting on the other side of the courtroom. “So this would not have been one of the media reports you were reviewing in relation to Kosovo at the time?” asked Pace. “If it was and I might have read it, I don't remember it 27 years later,” said Rubin.

The following day, the prosecutor turned to the allegations of crimes committed by the KLA. He asked whether their desire to be “on the side of the angels” also applied to the period from 1996. From 1996 to 1998, Rubin said that another US official was in charge, meeting with KLA leaders “at a time when we described them conducting terrorist activities”. That was “until we understood the situation better”. Rubin said that “after the KLA agreed to the Rambouillet Agreements, we regarded them as being on the side of the angels”.

Pace played a video interview with Rubin dating back to July 1999. In the video Rubin talks about allegations that Albanian forces were involved in assassinations and the KLA received drug money and criminal money. In the video, Rubin says: “We look into them, we can't prove them. If it were true, it would be deeply troubling.”

“But would it prevent a relationship with Thaçi now?”, the journalist asked.

“I think they are a force to be reckoned with on the ground, and if we want to create peace in Kosovo over the long term, we're gonna have to deal with Mr. Thaçi.”

“We have to take them once and all?”

“I think that's a fair summary, yes.”

Pace asked Rubin if he recalls saying that. “First I recall how young I look,” replied the witness with a laugh. “That sounds like me,” he added.

“A completely absurd theory”

Rubin was then confronted with several news reports from 1998 and 1999. A New York Times piece had covered the kidnapping of more than 200 Serbs, most of whom were thought to be killed. “If it was in the New York Times, it's most likely that I would have read it. I don't know that I would have regarded it as definitively accurate,” said Rubin. Another report by CNN had told the story of 15 prisoners held by the KLA found by KFOR German troops on 19 June 1999, while Rubin was in the region for the disarmament negotiation. The witness rocked back and forth, his mouth clenched. “Do you recall whether this report would have been brought to your attention?” asked Pace. “Very likely, and I would have liked the KFOR people here to urge no reprisals by ethnic Albanians against the Serb population for the mass attacks and suffering the Albanians have undergone during the Serb occupation.”

After the war, Rubin continued his political and diplomatic career, and between 2018 and 2020, he worked for the lobby firm Ballard Partners, which had a contract with the office of the president of Kosovo. The contract involved trying to reach a permanent peace agreement with Serbia. In that role, Rubin testified that he met or contacted various U.S. government employees in relation to Kosovo. It was also in that context that he last saw Thaçi in 2020. In June that year, Thaçi was heading to Washington to reach a deal with Serbia in a meeting hosted by US president Donald Trump. But it was then that the KSC prosecutor at the time Jack Smith announced the indictment against Thaçi and Veseli. Thaçi flew back home, and the meeting was cancelled.

“That troubles me,” said Rubin. “The fact that the defendant has been in prison for five years after voluntarily offering himself up to the court at a time when he was about to make a peace agreement with the Serb leader troubled me, that politics would enter into the rule of law.”

Pace asked whether Rubin had read the indictment, the prosecution's pre-trial brief, or watched any witness testimony, to which Rubin replied with a succession of “no”. “In this July 2025 televised appearance [shown by the prosecution], you stated Mr. Thaçi was prosecuted under a completely absurd theory that he controlled everything, which is obviously not true. That's what you said, right?” asked Pace. The judges sat straight up, listening attentively. “Sounds right. It's what I believe,” replied Rubin.

Nearing the end of the trial?

After Rubin, the Thaçi defence will present 10 more witnesses in court and will seek to admit one written testimony. The Krasniqi team will then have one witness in person and three in writing, if the judges allow it. Defence lawyers for Veseli and Selimi have instead announced in July that they do not intend to present any evidence. An estimated closing date for the defence case was set for November 14. The parties will then have a month to file their final brief and three more weeks to make closing statements. Then it will be up to the judges to come with their deliberations, for which they have around 90 days.

The KSC were set up ten years ago by the Kosovo parliament under pressure from the country's Western allies to handle ex-KLA fighters. The Chambers are formally part of the Kosovo judicial system but are located in the Netherlands and are fully staffed by internationals over worries of witness protection in the small Balkan country.