Togo seems as far as ever from deep political reform, as signalled at a workshop of the High Commission for Reconciliation and National Unity during the week of July 11 to 15. This body was set up two years ago and is supposed to support democratic transition.

In 56 years of independence, this West African country has been ruled with a firm hand for 49 years by the same biological and political family, the Gnassingbé family. At the moment, the country’s public institutions and the Constitution (which since 2012 no longer limits presidential mandates) are not conducive to democratic pluralism. These are all factors that undermine reconciliation in a country racked by frequent serious socio-political crises, often bloody.

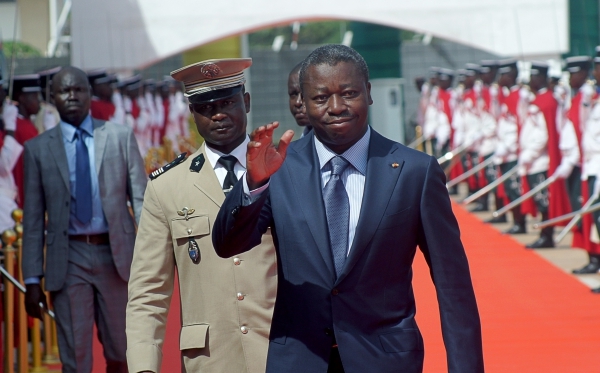

On July 21, the High Commission for Reconciliation and National Unity (HCRRUN) submitted to Togolese Head of State Faure Gnassingbé a document summarizing the conclusions of its workshop on reforms, held in Lomé from July 11 to 15.

Reforms

At the closure of the long-awaited workshop on July 15, Commission president Awa Nana stressed once again the need to implement a series of reforms to move the shaky Togolese democratic process forward. “Here and now nobody doubts any more the need to consolidate the democratic process and improve living standards,” said Nana, a female magistrate who is former president of the National Electoral Commission (1998) and of the Court of Justice of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). “The paths to be explored are diverse and transversal: respect for constitutional deadlines, readjustment of the political system, reformatting of parliamentary arrangements, creation of an electoral tribunal, consolidation of building a Republican army, managing tribal and ethnic participation in governance, modernizing property management and appropriate adaptation of the regulatory and anthropological framework for the exercise of administrative and diplomatic privileges of the governing class.”

The HCCRUN was set up on a recommendation from the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission (CVJR) -- which finished its work in April 2012 -- but has taken more than two years to start working. This workshop on political and institutional reforms was its first big initiative. The absence of such reforms has been polluting political life for a long time in this West African country, especially since the signature in August 2006 of the Global Political Agreement (APG) which called for them. Since the APG, which was signed in a context of high political tension 18 months after the massacre of over 500 people in election violence, there have been a series of political dialogues. All of them have generally come up with the same recommendations aimed at a return to the 1992 Constitution and reform of electoral provisions and public institutions, especially those involved directly in the electoral process. These are the Constitutional Court, the Independent National Commission (CENI) and the High Authority on Broadcasting and Communication (HAAC).

A Constitution made to measure

The current Constitution in Togo was adopted in 1992. Initially it was supposed to reduce the presidential mandate (five years) to two. General Gnassingbé Eyadema, who held power from 1967 and was re-elected (in contested circumstances) in 1993 and 1998, was therefore supposed to step down in 2003 at the latest. He even promised to do so! But in 2002 the National Assembly, which was totally under the thumb of “The General”, changed the Constitution and scrapped limits on the presidential mandate. So then, with a Constitution tailor-made for him, the man considered as one of the biggest African dictators had a clear path. He ran for office again in 2003 and unsurprisingly won another five-year term, during which he died in 2005.

When his father, supported by the army, died, son Faure Gnassingbé seized power amidst a bloodbath. Since then, he has also got himself re-elected. Under pressure from the opposition and the international community when he took power, Faure Gnassingbé and his political party promised in 2006 as part of the Global Political Agreement (APG) to introduce political reforms. The aim was to open up and modernize public institutions so as to create the conditions for democratic pluralism. Ten years later, after numerous talks, the reforms have still not been implemented. Faure Gnassingbé is now on his third mandate. And this is the heart of political debate in a poor country where, according to the organizers of the “Let’s Turn a New Page” campaign, 88% of the population have known only one regime in power. This is unique in Africa.

Electoral farce

After another election in 2015 with the same result, the debate on reforms has become tense. Street demonstrations, meetings and public debates are increasing. Some public figures, disappointed by the broken promises of government, decided not to participate in the highly mediatized workshop of HCRRUN. The Fight for Political Pluralism (CAP 2015), which includes several political parties including the parliamentary opposition, also boycotted the workshop. “The HCRRUN initiative looks very much like subterfuge aimed at helping the current authorities to bury the reforms proposed by the APG as a solution to the political crisis our country has been going through for decades, a crisis deepened by the successive farcical electoral processes, especially the disastrous presidential polls of 1998, the bloody elections in 2005 and the grotesque ones of 2015,” wrote opposition leader Awa Nana, president of the HCCRUN, on June 13 this year.

Awa Nana, who was president of the National Electoral Commission in 1998, stepped down a few days after the polls without announcing the results, whereas everything was pointing to a defeat of General Eyadema. The Security Minister at the time, General Séyi Mèmène, took advantage of her resignation to announce victory for Eyadema, an ex-sergeant demobilized from the French army and president of Togo since 1967. On the eve of the workshop, Awa Nana broke the silence she had kept for 16 years. She denied having been part of any electoral hold-up in favour of Gnassingbé Eyadema. She said she had rather been put in a minority by the resignation of several other members of the electoral commission. Her version of events met sharp criticism in local media. The whitewash operation seems to have had mitigated success. The workshop nevertheless gave rise to numerous public stances by participants including leaders of political parties, civil society actors and religious leaders.

In an interview on the Togolese government website, European Union representative to Togo Nicolas Berlanga-Martinez warned that “the plethora of dialogue initiatives without tangible results also contributes to people’s feelings of frustration and resignation”. He added that “mutual consultation and trust building built on diversity of opinions are needed if there is to be a constructive dialogue”. The European diplomat thus transmitted a feeling much shared by Togolese citizens that whilst there is much talk, nothing is being done, and there is so far little sign of change.