Three years after Colombia’s peace deal, the country still doesn’t know exactly how former rebels of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and members of the Armed Forces who committed war crimes during the country’s 52-year-long armed conflict will be punished. Detailing these sanctions is probably the biggest challenge for the country’s transitional justice system this year. It will also become a litmus test for how legitimate its efforts to judge perpetrators are, in a fractured society where citizens still equate justice with prison and the governing party campaigned against a novel approach to accountability that it has portrayed as impunity.

Even though Colombia’s Special Jurisdiction for Peace – or JEP, as it is locally known – began working in early 2018, it has yet to determine the precise guidelines for its alternative sanctions.

Colombia’s sanctions on paper…

This delay has to do with the fact that the Colombian transitional justice model devised an innovative formula that hasn’t been tested elsewhere, combining elements of retributive and restorative justice. The result is a two-track system that will mix both types of penalties – punishment and repairing harm. Former FARC combatants, as well as members of the military and other persons, may receive more lenient sentences for serious and representative crimes, such as murder, kidnapping or sexual violence, if – and only if – they fulfil three conditions. They must acknowledge their responsibility, tell the truth, and personally redress victims. In the end, when they fulfil this checklist, they qualify for a special sanction of 5 to 8 years in a non-prison setting. Should they not, they will face sentences ranging from 5 to 20 years under ordinary prison conditions.

The idea behind this incentive is that those persons responsible may come forward and own up to their role, allowing the JEP to build its cases quicker than in an adversarial system. In turn, this should avoid the tribunal from collapsing on account of the enormous legacy of atrocities it has to prosecute in a country where 8,9 million persons – out of a population of 48 million – are officially registered as victims.

…and in real life

However many details on sanctions have not been specified. What kind of non-prison settings will be chosen is still a mystery. Will a person have to redress his or her own direct victims or may repair other communities that endured the conflict? Will those who have already entered politics be forced to abandon elected office once they are convicted?

This conundrum exists in part because several institutions, including the Constitutional Court and the Congress, have kicked the ball forward to the JEP without addressing the issue. At the end of the day, it will be up to the JEP’s 38 justices to determine what sanctions will look exactly like. So far the special peace tribunal is taking its time, in part because it seems unlikely that it will present its first indictment before mid 2020. Currently its Judicial Panel for Acknowledgment is building seven macro-cases detailing different representative crimes and identifying those responsible for them. Two of these focus on FARC’s involvement in kidnapping and forced recruitment of child soldiers; another case details extrajudicial executions by the military, while several regional cases document human rights violations carried out by various actors.

Simultaneously, the JEP created a task force comprising one magistrate from each of its judicial panels and chambers to begin discussing sanctions. In a bid to ensure they abide by both Colombian law and international standards, they have met with lawyers from the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in San Jose. They even discussed sanctions over lunch with the latter court’s nine justices last September in Bogota.

No timeline in the horizon

In the JEP’s view, defining the alternative sanctions regime has to be the result of a complete legal process for each case, including its investigative and judgment phases. Its magistrates believe, for example, that it would be difficult to outline sanctions before identifying the victims or the harm they suffered in each of the macro-cases it will open. They also think it is still not possible to gauge how many of the 9,713 former FARC members and 2,291 members of the armed forces who have requested to be under the JEP’s jurisdiction will be deemed most responsible of committing international crimes. Or that much crucial information will only arise as perpetrators are confronted with victims’ accounts.

“In cases where there is an acknowledgment of responsibility and full contribution to truth, the resolutions will include a proposed sanction, built not only on attending to what victims understand as redress but also in a dialogic exercise with perpetrators,” says Juan Ramón Martínez, a professor in international law and one of the five justices on the JEP’s First Instance Chamber in Cases of Acknowledgement of Truth and Responsibility, in charge of defining sanctions.

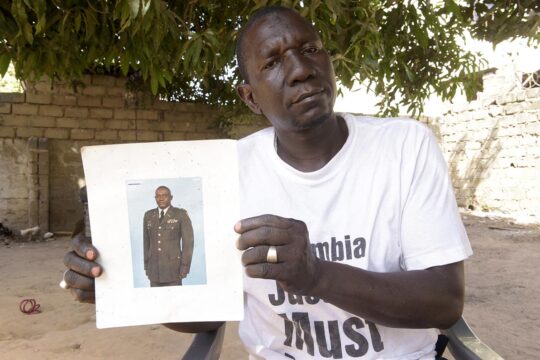

One of the JEP’s concerns is to be able to consider ideas of redress tabled by victims. For example, relatives of a group of state legislators kidnapped by FARC in 2002 and murdered by them five years later agreed on requesting that their perpetrators build a school in either Pradera or Florida, two towns in their home state of Valle del Cauca heavily ravaged by war. In the victims’ families vision, it would double as a memory site, with each classroom donning the name of the twelve assemblymen. “For me, redress that endures over time is more important than a jail sentence,” says 22-year-old Sebastián Arismendy, whose father Héctor Arismendy was one of the victims. “My father used to say that the only thing he could leave us was an education. It seems fitting that the sanction for everything that happened to us is a school built by former combatants’ hands to provide education in an area ravaged by war.”

Listening to victims’ demands means that most restorative sanctions would be defined on a case by case basis. It also poses a significant practical challenge, given the number of them who have come forward. In the single case on kidnappings, 1,276 victims have been certified. “Sanctions cannot be written in stone. They require flexibility, given the complexities regarding the universe of victims, the amount of offenders and the diversity in actors involved in our conflict,” says Justice Martínez. This would mean that the first sanctions ordered by the transitional justice system would not be ready before late 2020 or early 2021.

When legal and political timeframes clash

Defining the alternative sanctions regime is perhaps not the most urgent task from a legal standpoint. But politics may suggest otherwise. Colombians seem hardwired to the retributive aspect of them. Polls throughout the Havana peace talks showed that they overwhelmingly disagree with the possibility of FARC members eventually entering politics without going through prison.

This reality became evident during the campaign for the peace deal referendum in October 2016, as current President Iván Duque and his political party centred part of their campaign against the accord on the vagueness of sanctions for FARC commanders. After 50.2% of Colombians rejected the original deal, this became a critical issue during the ensuing renegotiation. Marta Lucía Ramírez, then one of the opposition leaders and now the country’s vice-president, proposed that these sentences be carried out in agricultural penal colonies.

Duque and Ramírez have shied away from the topic of sanctions since winning the 2018 elections, but it would be politically naïve to ignore that large segments of Colombian society are still asking questions on this issue. Many cannot understand why ten former FARC commanders were elected to Congress but have yet to acknowledge their responsibility and show remorse. Or how Guillermo Torres will become the first ex-FARC member to hold public office locally as mayor of Turbaco without redressing any victim. What might seem like a merely technical or legal discussion in fact has political ramifications that could affect the JEP’s legitimacy.

Not only Colombians are pressuring the JEP on this. Fatou Bensouda, prosecutor of the ICC, included the issue in her end-of-year report, stressing that her office considers “the imposition of effective penal sanctions that serve appropriate sentencing objectives of retribution, rehabilitation, restoration and deterrence” a relevant benchmark for 2020.

Can pre-trial detentions apply?

One issue threatens to become a time bomb: what happens to former FARC rebels who have been convicted by Colombian courts in absentia, while they await their sanctions in the transitional justice system?

The Constitutional Court allowed for the suspension of previous sentences. The peace accord does not include any remand provisions but it allows them to deduct time from their sanctions provided that they redress victims and meet the conditions relating to the effective restriction of liberty, including that they should remain in a specific location where they can be monitored and any movement is authorized.

The problem is that this hasn’t really started happening because there is no system in place to monitor who is complying and who isn’t. Theoretically, this task should be carried out by the United Nations mission in Colombia that verified their disarmament and destroyed their weapons. But this part of their mandate has not been negotiated yet. The result is that many of the 13,046 FARC members who laid down their weapons in 2017 and began their reincorporation are roaming around the country freely. By August this year only 25% of them remained in the 26 original encampments established by the Government, a Congressional report found. This situation represents a significant risk for FARC members, given that they will probably be denied the deduction benefit for the time they spent in the reincorporation camps due to the lack of any verification mechanism.

In light of this, JEP presiding judge Patricia Linares insisted on the need for the UN mandate to be addressed during a UN Security Council’s official visit to the country last July. “All 15 members pledged their support on this, which we expect will duly materialise,” says Justice Martínez. Six months later it still is a pressing question.

The uncertainty could prove dangerous at a moment when one faction of the former guerrilla chose to rearm and is actively seeking new recruits. “The important thing is to have clearly defined parameters and a sanctions regime,” says Luis Alberto Albán, a former FARC commander who participated in the peace talks and currently sits in the Senate. “What is clear to us is that the early activities redressing victims must be duly certified and taken into account,” he adds.

The JEP’s quandary about the government

Another dilemma is that the JEP needs the political support of President Duque’s government, which has been openly hostile to it. Several key provisions on alternative sanctions are impossible to determine without active collaboration from the government. For example, one idea justices are considering is choosing the current reincorporation camps where former rebels are transitioning to civilian life as potential locations for their punishment. Even though it’s up to the JEP to decide where ex-FARC commanders will be penalised, upkeep of these spaces and its inhabitants is the government’s legal responsibility.

Likewise, negotiating with the United Nations a mandate that enables it to monitor former rebels’ compliance with sanctions, as the peace accord states, is the sole responsibility of Duque’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

For the JEP to offer a novel theory for many budding peace processes around the world, it needs to define what sanctions will look like.

So far the JEP has met five times with Emilio Archila, Duque’s official in charge of the peace deal’s implementation, to determine how restorative sanctions can go hand in hand with the special development plans that are also considered as reparations for regions heavily affected by war. They have also spoken with Environment Minister Ricardo Lozano on possibly signing up former rebels to conservation efforts as a form of reparation. “There are legal and constitutional obligations that must be fulfilled. We are fully confident that the Government will understand them,” downplays Justice Martínez. But few other instances of cooperation with the government are being seen.

In the end, much of the JEP and the entire transitional justice system’s legitimacy hinges not only on its ability to strike a balance between retribution and restoration, but also in offering Colombians a clear definition of its alternative sanctions that can allay their fears. “For the JEP to offer a novel theory for many budding peace processes around the world, it needs to define what sanctions will look like,” says Santiago Pardo, who leads the Access to Justice Design Lab at Los Andes University. “That’s what’s really a novelty.”