The relatively short 12-page text aims to set up a new institution in the Central African Republic originating from the 2015 Bangui Forum and considered one of the pillars of the February 2019 peace accord. Even though the three-month deadline for launching it has been completely missed, provisions for elaboration of the bill have been respected with national “popular” consultations organized in the seven big administrative regions. A total of 1,977 participants from different components of society (religious groups, minorities, political parties, etc.) were consulted and the results compiled in a report serving as a basis for the bill.

The report’s conclusions have been largely respected in bill, of which Justice Info has obtained a copy. According to this text, which still has to be approved by parliament, the Truth, Justice, Reconciliation and Reparation Commission (TJRRC) will be a new institution which “does not have judicial power”. It will, however, have “autonomy” and “independence of action”. It will have a four-year mandate (can be extended for one year) and will be composed of 11 commissioners, from all seven regions of the country and including at least four women. They will be appointed by presidential decree after selection by a committee. This committee is to be composed of 7 personalities, including one from parliament, one from the government, three from civil society and two international observers (United Nations and African Union). The commissioners will work “full time” for the Commission and meet every week.

An ambitious mandate (1959 to 2019)

The bill provides that the TJRRC be organized around three organs – the plenary Assembly (bringing all the commissioners together), the Secretariat and the sub-commissions. It will be tasked with “investigating, establishing the truth and situating responsibilities concerning the serious national events from 29 March 1959, date of founding president Barthélémy Boganda’s death, up until 31 December 2019”. This is nothing if not ambitious. The national consultations report has already established a long list of the events to be covered: the coups d'État in the country, with or without the involvement of foreign forces; foreign military interventions; use of mercenaries; serious violations of human rights; and political governance. One might ask what pressure the Commission could exert on France, Russia, China or even the CAR authorities to make them reveal the truth about these events.

In addition, the TJRRC is to organize thematic hearings "on the major violations committed ... and the role played by state or private institutions, such as the army, police, justice, education, the financial sector, the media, political parties and their affiliated movements, religious denominations, associations, armed groups and other organizations”. However, its time is limited -- to a maximum of 5 years. Hence perhaps the bill’s lack of precision on the historical angles of investigation, something specified in the consultation report. But researchers and historians say the desire to "facilitate collection and archiving of vestiges and data of armed conflicts in the CAR" is one of the measures provided for in the bill.

On reparations, the concepts included in the bill are taken from the national consultation report, which envisaged symbolic (memorial), collective, or individual reparations.

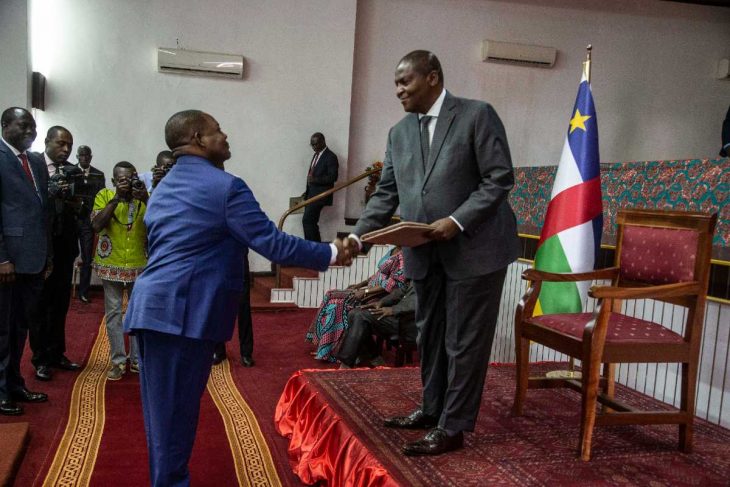

While the Commission will not have judicial power, everything in the description of its future investigative work looks like it could be mistaken for that. It starts with the filing of a complaint. “Without prejudice to the right of any individual to go to the courts for the defence of their interests, any group of persons suffering from an individual, collective or massive violation of human rights can seize the TJRRC by filing a complaint,” says the bill. This complaint is to result in a document bearing the name and status of the complainant and of the suspected perpetrator(s), as well as a description of what happened. The complainant can choose if he or she wants to appear in public hearings or behind closed doors. The Commission can also take up a case on its own initiative, and all proceedings before the TJRRC will be free of charge, says the draft law presented to President Touadéra.

Extensive investigative powers

The Commission’s scope for action is quite interesting. The commissioners, who are to have immunity within the context of their mandate, can call upon any person who will then be “freed from professional secrecy”, including people “benefitting from immunities or privileges”. The Commission may access “any information or public archives for the fulfilment of its mandate, which confers on it a power of injunction”. In the same vein, it is to be able to visit “any place or premises” with the accord of the local judicial authorities, or require their services to carry out searches.

Pragmatically, however, the TJRRC bill provides for a mechanism of conciliation between victims and perpetrators. If “the recommendations of the TJRRC […] duly notified to the parties, are actionable for them”, and if “the reparation is carried out according to the friendly settlement procedure with the consent of both parties”, then this reparation is to be considered res judicata,” says the text, which adds that if one party does not conform, the other one may “seize the courts and tribunals according to common law to obtain implementation by force”.

The bill also covers matters of forgiveness. It envisages “organization of a ritual for certain cases of national reconciliation” and the possibility of using “traditional and neo-traditional reparation and reconciliation mechanisms”, saying that “victims may grant their forgiveness if it is freely done, without any kind of interference”. This also raises questions about the kinds of pressure that victims in the interior of the country, still largely controlled by armed groups, may be under to grant their “forgiveness”.

Cooperation with the courts

Whereas the national consultations report was relatively precise about the possibilities for cooperation between the TJRRC and the Special Criminal Court or national courts, the bill remains fairly vague on this point. The Commission, says the text, “works with the Special Criminal Court and national jurisdictions in the search for truth and justice” and “can make recommendations on the transfer of case files to the Special Criminal Court and other competent jurisdictions”.

Finally, the bill raises the key question of the Commission’s budget but remains quite evasive. It provides for an allocation from the State budget, saying at the same time that “bilateral, multilateral and other partners can also contribute to the budget”. This point is crucial, since the creation and effective operation of a TJRRC mooted since 2015 will depend largely on the resources put into it.