In January 2007, Yahya Jammeh, the autocratic leader of the Gambia, a small West African country, appeared “with a bag of herbs and made a diabolical statement,” said Essa Faal, the lead counsel of Gambia’s Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC), charged with investigating human rights violations under Jammeh’s rule (1994-2017).

Jammeh had laid claims to discovering a dose of herbal concoction that would cure HIV/AIDs in three days. His treatment has since been veiled in secrecy. But after more than two months without public sessions due to the coronavirus pandemic, the TRRC has resumed hearing testimonies on October 12 and new evidence continued to lend a rare and unique insight into a treatment that proved to be both a sham and a killer.

During one week last July and in the past week, 10 patients, 3 medical doctors, 3 lab technicians and Jammeh’s former aide de camp who all participated in the treatment described it a “hoax”.

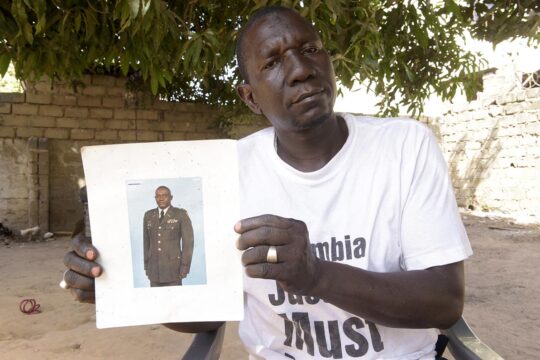

In the last eight years of Jammeh’s 22-year rule, pictures accompanied praising songs on national television showing him treating patients. Jammeh claimed his treatment was successful by rubbing patients’ bodies with herb pastes and by giving them herbal potions. The self-named “leader of the people of faith” was brandishing around with a Quran, prayers beads and, occasionally, a miracle water he would throw at his supporters. “The treatment was just to empower the president. There was never a cure,” said last July Landing Momodou Faal, a lab technician who had been working with Gambia’s ex-ruler on his alternative AIDS treatment.

The dilemma between upholding ethics and surviving

Jammeh’s announcement of herbal cure for AIDS was a nightmare for the medical and scientific community who knew the cure was a hoax but said they could not do anything about it. Dr Assan Jaye was leading a HIV/AIDS treatment programme at a UK-sponsored Medical Research Council (MRC) hospital in Banjul, the capital city, when Jammeh announced his cure. Under his department were 1600 patients, 500 of whom were on conventional treatment. Last week Jaye told the TRRC that the announcement was shocking but that they initially discarded it as part of the dictator’s political rhetoric. It became real when some of his patients and those whose condition he was monitoring came to him to announce that they were joining Jammeh’s treatment.

The situation was to become a cruel dilemma for Dr Jaye and his team, as well as for a number of medical staff who had to deal with Jammeh’s new and deadly hare-brained idea. For Dr Jaye, Jammeh’s claim was “rubbish” but they couldn’t afford a clash with an all too powerful autocrat. They had to inform their patients – whom he said were doing very well – of the risks involved since they would be taken off their conventional treatment for an untested herbal concoction.

Abdoulie Batchilly was a lab technician at the country's only referral Royal Victoria Teaching Hospital, now renamed Edward Francis Small Teaching Hospital. “It was the most depressing period of my life because I knew what we were doing was not authentic. I was scared for my safety and the safety of my family,” he said before the TRRC.

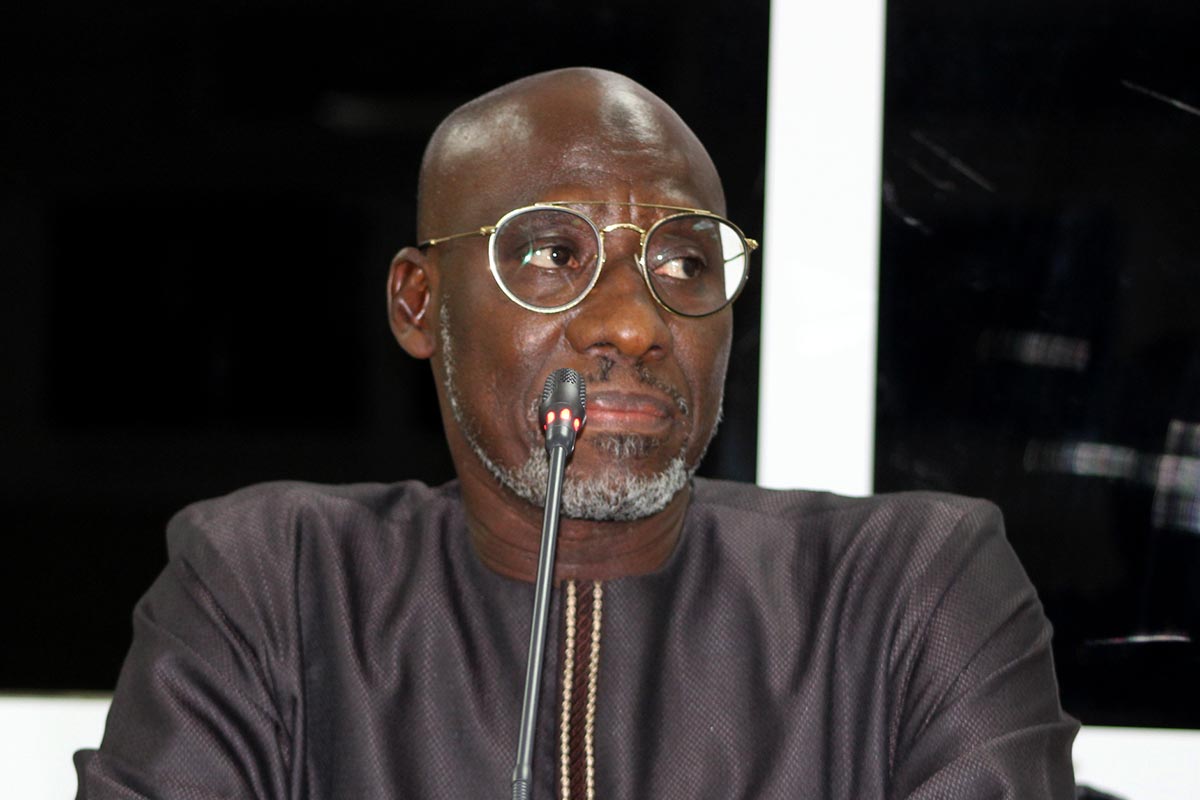

The endorsement of Jammeh’s cure by Dr Mbowe

Batchilly tested two post-treatment patients from Jammeh’s AIDS programme. They both tested positive to the virus. Jammeh did not like that, Batchilly testified. After those two tests in the Gambia, samples were sent to a lab in Dakar, Senegal. Some samples came back showing a very low viral load. But Batchilly said the results were wrongly interpreted by Dr Tamsir Mbowe, the director of Jammeh’s treatment programme, to mean that the patients were cured. Batchilly said he confronted Dr Mbowe over his announcement. (Batchilly testified via a video link from the United Kingdom where he has lived since leaving his country over Jammeh’s fake AIDS treatment.) A Senegalese HIV/AIDS expert, professor Sulayman Mboob, whose lab had been used to conduct the tests, also wrote to refute claims that samples tested in his lab showed Jammeh cured the virus.

“If you say you cure HIV based on an increased CD4 count and suppressed viral load, that is not a cure. You need to do a pro-viral DNA test to [establish that you] eliminate the presence of the virus in the cells,” explained Dr Jaye. But Jammeh and Dr Mbowe would not be deterred. “This cure, unless one ignores it and says this is not possible, this is 100% [true]. These people had the virus and it has been confirmed through testing. After 10 days of testing, the virus disappears from the body. What do people want now?” Dr Mbowe told national broadcaster GRTS, in 2007. Even when his colleagues like Dr Mariatou Jallow, a former director of Edward Francis Small Teaching Hospital who appeared before the TRRC last July, Batchilly and a host of others silently protested, Dr Mbowe maintained the cure was true.

“The President shortened these people’s lives”

Months into Jammeh’s treatment, not only did medical practitioners realize it was a fraud, a lot of patients also did, said Dr Jaye. Those who were quick to notice the treatment was a fake returned to Jaye’s clinic at the MRC. “Their health was in a state of hopeless decline,” Jaye recalled. “Some died, no matter how much we tried, some survived.” Dr Jaye said that there was evidence that the longer one stayed on Jammeh’s treatment, the worse their condition got. “There was a sizable number that got retained for a long time. That group that got retained in Jammeh’s programme, their condition [had] deteriorated by the time they came back to the MRC.” Others died without ever making it back to the MRC. “We knew that some people died because we knew the people on his treatment,” said Dr Jaye. “That was the sad thing about it because these were people that we had managed to a good level of health. Unfortunately, the President shortened their lives. Those people were not supposed to die.” The Truth Commission is yet to establish how many people died.

The MRC knew that though they couldn’t turn away patients, if they did not close their HIV clinic Jammeh would come after their whole hospital. “We were caught between saving our research mandate and clashing with a political power. The fact that these people had gone to a presidential treatment and were coming back could cause a political problem and may compromise our research mandate. We decided [to] close our HIV clinic at the MRC,” said Dr Jaye. Before closing their clinic, they sought funding from London to support the Edward Francis Small Teaching Hospital to be able to handle the HIV/AIDS patients. Meanwhile and up until 2018 Dr Mbowe still believed the treatment worked, as would indicate his statement before the Janneh Commission, a financial inquiry into the activities of Jammeh. He is now expected to appear before the TRRC and respond to the allegations against him.