JUSTICEINFO.NET IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS

Éric Émeraux

Former head of the French Central Office for the Fight against Crimes against Humanity

For three years, Colonel Eric Emeraux headed France’s Office to Fight Crimes against Humanity, which has some 20 investigators specialized in the repression of international crimes. After his retirement and the publication of a book, "La traque est mon métier" (Going after people is my job), he explains frankly the conditions and limits of this exercise in the French, European and international context.

JUSTICEINFO.NET: What did you find when you arrived at the Central Office to Fight Crimes against Humanity (OCLCH)?

ÉRIC ÉMERAUX: I arrived in September 2017, after spending five years in Bosnia-Herzegovina as security attaché at the French embassy. Before that time, which was very important in my career, I had not necessarily been much aware of issues of war crimes and crimes against humanity. The main things I dealt with in the judicial police were fighting organized crime and homicides. In Srebrenica, I attended a first big ceremony in commemoration of the genocide, on July 11, that brought me squarely into the pain of the victims. It left quite a mark on me. And what left even more of a mark in contacts with Croats, Serbs and Bosnians, was to realize that they had all lived through the civil war and suffered to various degrees. That period raised lots of questions for me.

When I arrived at the Office, the situation was not great. It had only recently been created, needed to develop and exist in a competitive way. The climate was one of immediacy, where public security issues were the ones preoccupying politicians, but weren’t we supposed to work on the imprescriptibility of crimes against humanity that happened in the past? In Africa, in the Balkans an educational effort was needed vis-à-vis the bosses within the gendarmerie, given that the mandate of the Office, created by a decree of 2013, is threefold: the most serious crimes; hate crimes which we have not worked on much because overwhelmed by the first aspect; and the tracking of fugitives involved in crimes against humanity.

We are no longer working on cases dating back 25 years, such as Rwanda, but entering the present time.

What are the arguments that work with your hierarchy?

If you don't bring these issues down to the everyday level, you might as well give up. They began to come to the forefront from the moment we started receiving files of "1Fs", rejected asylum seekers. These are people who are strongly suspected of involvement in crimes against peace in their country, who have applied for protection and for whom, after analysis, OFPRA [French Office for the Protection of Refugees] deemed that they were neither protectable nor deportable. They are on French territory and so represent a potential threat on a daily basis. That's what's important. And hate crimes too, because when Jewish cemeteries were desecrated in Alsace, everyone was worried.

There is a third very important aspect here, which is international cooperation. When I arrived, Europol [European police agency] quickly created the AP CIC, a coordination group on international crimes that integrates Syrian and Iraqi issues and everything related to conflict in the Middle East. Our litigation, which was very focused on Africa, then began to shift to a large volume of Middle East cases. We are no longer working on cases dating back 25 years, such as Rwanda, but entering the present time. As all of this is grafted onto the national and European counter-terrorism problem, and as we can treat the same individual not only from the perspective of terrorism but also from the perspective of war crimes, this brings the litigation back to everyday life.

There is Europol, but also integrating our work with structures like the IIIM [International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism on Syria], UNITAD [UN Investigative Team to Promote Accountability for Crimes Committed by Daesh] and the Genocide network. All of this has meant that we have done rather well, notably with the setting up of a joint investigation team with the Germans on Syria. This has kind of brought the Office from the shadows into the light.

In the wave of refugees, 95 % are victims of the Bashar al-Assad or other regimes, but there are also perpetrators who want to buy themselves security.

How many cases do you have?

When I arrived, we had 60 case files, which is already good. But in three years we went from that to 150. From 2017, the wave of “1Fs” arrived. We found ourselves with Taliban, Sri Lankans, Chechens and of course lots of Syrians… it was the whole world. In the wave of refugees, 95 % are victims of the Bashar al-Assad or other regimes, but there are also perpetrators who want to buy themselves security. We need the capacity to try these people efficiently. We can’t have one strong link in the chain if the others are weak. I’m not talking just about the investigations part. We need the means to try people within a relatively short time.

Is this not the case?

No.

In July 2019, a National Anti-Terrorist Prosecutor's Office (PNAT) was created, which became part of the Prosecutor's Office for Crimes against Humanity. Was this a good idea?

I don't really have an opinion on that. Nevertheless, it gives a transversal approach to the handling of cases. It seems important to me that there should be a two-pronged approach to the problem in cases such as Syria or Iraq. Here, we are talking about two categories. We have our French jihadists, to whom we can possibly attach war crimes charges. And we have the foreign jihadists, who have come to take refuge in Europe, who can also be treated in both ways. So it's still easier when you have everyone [anti-terrorism and war crimes] on the same level to exchange. This too has been the subject of coordination efforts with magistrates and police colleagues from the anti-terrorism department and with the intelligence services.

Hate crimes division works upstream of other crimes. It captures the negative impulses of a society, which always revolve around homophobia, anti-Semitism and the exclusion of others.

On the human resources side, however, you haven't made much progress...

That's for sure. At the end of the year, the Office will still have 30 men and women [compared with 19 two years ago]. Four policemen and 26 gendarmes. We benefited from the creation of a hate crimes division. That means ten more people. It's very important because, in the end, this division works upstream of other crimes. It captures the negative impulses of a society, which always revolve around homophobia, anti-Semitism and the exclusion of others.

Let's talk about investigations. When it comes to international crimes, there are the witnesses in many different places, the geographical and temporal distance, the multiplicity of actors, the lack of cooperation from the States on whose territory the crimes are committed. How do we integrate all this and ensure that the investigations are successful?

Since 2017, we've been honing our practices a bit. We still have a national component, which is quite traditional, since it involves implementing special investigative techniques found in other litigation, such as organized crime and terrorism. The international component is more complex because it is necessarily linked to the good will of the country where the atrocities were committed. But here too, over the past three years, we have managed to open a few doors. If we talk about Rwanda, things have improved because our President and the President of Rwanda have tried to find common ground. Then we opened a case linked to Liberia, where we were the first to investigate.

Belgian investigators were unable to travel to Liberia. What makes you able to do that?

We have an embassy. The fact that I worked with the Foreign Affairs Ministry in Bosnia allows me to understand how it works. One cannot evolve in a country if one does not have the support of the embassy, the liaising magistrate where there is one, and the internal security attaché. In Liberia, it was the ambassador who went to the authorities to defend an international rogatory commission and get the green light to work. Then we opened a case on Chad and we were going to open Sri Lanka, but we were blocked because of Covid-19.

The trap you must not fall into is getting bogged down in politics and diplomacy. If you stay with the technical aspect, it's fine.

Can we talk about diplomatic deals, with Rwanda for example?

It’s simply the warming of direct diplomatic relations between the two presidents. And then there was an important event, the arrival at the head of La Francophonie [international organization of francophone countries] of a Rwandan woman. All those who had been speaking with us in English in Rwanda suddenly discovered that they spoke French! It was funny, but that's part of the game. What is important is to stay with the technical aspect. The trap you must not fall into is getting bogged down in politics and diplomacy. If you stay with the technical aspect, working with people in-country who do the same, it's fine.

You say you have been honing your practices. Does that involve tools?

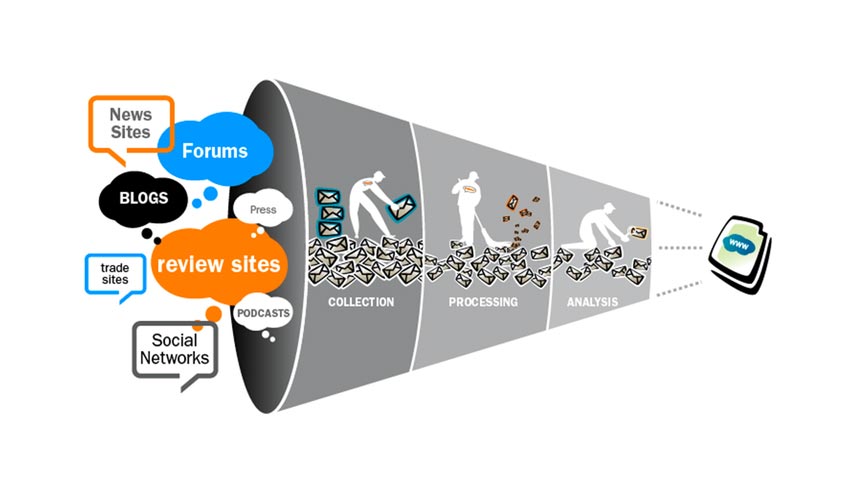

A lot of OSINT [open source information] tools have been developed. I'm not going to go into too much detail because those who help us don't necessarily want to be named. In traditional cases, most of the time, you have a crime scene with a corpse and, from the corpse, you can trace the perpetrator. For international crimes, most of the time we are assigned a perpetrator and we are told: he is involved in this or that thing, now prove it. The intellectual path is the opposite. We have therefore worked on setting up tools that allow us to integrate contexts. If the data has been correctly entered, we will see a complete architecture of the situation at a time "t", with who does what, who controls whom. This is what some Syrian NGOs have done, modelling the entire architecture of the country, with who is in charge, who is behind it, etc.

Could you be more specific?

At one point, to make up for the lack of manpower, I looked into artificial intelligence. We developed the possibility of doing quite advanced research on the digital world, on what is called the surface web and the non-surface web. This research serves both the hate crimes division and the crimes against humanity division. A double entry platform is used. If I want to know everything about Boko Haram from 2013 to 2014, I will be able, with certain specific tools, to receive a fully integrated report with a whole bunch of data, including video; and if I ask for a full French translation of the report, I get it; and if I want an update every 24 hours, I get it. This is what we call structured data. It can also be done on an individual. What some people used to do by hand, we can do today with fast data tools. These are research techniques that are now used and integrated into procedures.

Have they been legally validated?

It is too early. But concretely, there is no reason why they should not be. It's a question of getting everything into procedure properly. If we do a search on Facebook and Facebook gives us a username, which brings us back to a phone number, which allows us to launch a judicial eavesdropping procedure, all this is done in a classic procedure. It's the same here, except that we do it in a more automatic way.

For Kabuga, we did traditional investigative work, with cell phones, as in any organized crime or homicide investigation.

Is that what led you to the arrest of Rwandan suspect Félicien Kabuga last May in the Paris suburbs?

No, for Kabuga we did not use the platform specifically. We did traditional investigative work, with cell phones, as in any organized crime or homicide investigation.

There is a question that hasn’t been answered: Why wasn’t he arrested earlier? Is it the fault of your predecessors, or the UN Mechanism?

I would say two things. The first is that Serge Brammertz [the prosecutor of the Mechanism] created a task force that met twice, to facilitate exchanges between the stakeholders. This is to his credit. The second important point is that my predecessors had indeed received requests for international criminal assistance, but how does it work? We are told: go and check if our friend is not attending midnight mass at a particular place. These are very precise, very focused missions. We got out of that system and we used our own procedure, in this case article 74-2 of the code of criminal procedure, which allows us to search for fugitives in general and gives us all the prerogatives to investigate and catch someone red-handed. That was the key to success, in fact. That and a piece of intelligence.

A piece of intelligence?

It was a pure coincidence of police circumstances. I get along very well with my colleague at the Metropolitan Police (MET) in London. They observed that one of the members of the Kabuga family was moving, leaving English territory. They didn't know if that person was going to Belgium or France. We realized that they were coming to France. That was the first lead. First there was Brammertz's determination, then the tip from my English colleague. All of this meant that, on the morning of May 16, when we were at the door of the apartment in Asnières, we were still not sure that Kabuga was there, but we had good reason to believe that he was.

And that could not have been done before?

Before, we didn't have confinement. Confinement has enlightened us on many things. We had already realized that the whole family was frequenting this apartment. With the confinement, nobody could move anymore. We had to get someone to come to the bedside of the elderly person. It was the son, Donatien. The objective element that made things easier was the confinement. The person who was in charge of the investigation was stuck at home, she was able to free up some time. She started to follow a lead, then gradually it got bigger and bigger and we thought, "But he's here!”

At the European level, we should create a joint international investigation team that would be a kind of franchise that could be reused on all types of litigation. Europe must invest much more in the fight against impunity.

So is cooperating with other investigating teams in Europe essential?

This is my vision, and the one I am working on with my British colleague at the MET. At the European level, we should create a task force or joint international investigation team that would be a kind of franchise that could be reused on all types of litigation. I've always believed in joint investigation teams, because it's a good way to get around a certain number of difficulties. If we manage to create a dynamic, as we managed to do with the Germans on Syria but also with the British on Rwanda, we can achieve results. This is true for the other European countries. I think that Europe must invest much more in the fight against impunity than it does today. It has not done so – which was normal and logical - because it has been taken up with the whole counter-terrorist dynamic. We're still there, but I believe that Europe has a duty to make the fight against impunity, against atrocities, part of the fight at a certain level. There is certainly room for improvement in this area.

In France, the legal framework of universal jurisdiction is more restrictive than in Germany. Is this a stumbling block?

No, in any case not a big one. But if we want to change things, I think it would be good to align ourselves with regard to the presence [of the suspect] on the territory. Of the five offences covered by the Office, we have three - crimes against humanity, war crimes, genocide – linked to habitual residence, and we have two - enforced disappearances and torture - linked to presence on the territory. It would be good to align the five offences with regard to presence.

The other element that has caused us problems was to realize, when we had to deal with cases of young Africans tortured in Libyan jails, that we were limited in terms of jurisdiction, because the 1984 New York Convention only includes State torture. With hybrid organizations or militias, which are not necessarily linked to a State structure, we have a problem. If we want to pursue the problem of human trafficking, we will have to look into this question.

This is the specificity of this Office, to work with civil society. I consider them to be sources, and our work is to put into legal form what they have been able to achieve.

Your sources of information are multiple and eclectic, how do you deal with them?

The specificity of these investigations is that they have to be integrated into a whole range of structures. If we talk about international organizations, there is the International Criminal Court, with which we work only from the angle of requests for international criminal assistance; the various UN mechanisms, notably the one on Syria with which we have many exchanges; then there is Europol, the Genocide Network and Eurojust, Interpol. Then there are the NGOs, and this is the specificity of this Office, to work with civil society. I consider them to be sources, and our work is to put into legal form what they have been able to achieve. There are the so-called context NGOs - Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch - which can shed light on a region at a given moment. There are the evidence-seeking NGOs, specialized on an area, such as Civitas Maxima for Sierra Leone and Liberia, the Civil Party Collective for Rwanda, and all the Syrian NGOs. A third category is NGOs specializing in a particular area, such as We are not Weapons of War on rape in conflict or others specializing in Open Network Sources, for example, or tracking criminals on social networks.

What is the quality of evidence provided by these NGOs?

That depends. I think that now they have understood that if they want to bring to justice the individuals they have detected, they have to align themselves upstream. We are here to help them "calibrate", to tell them: your story is good, but we will have to help you find victims and witnesses, real testimony. Once they have detected an individual, the magistrates detail the legal qualifications and then seize us, if necessary. Once we are seized, most of the time we come back to these NGOs to complete the file, to obtain elements in the procedure of which they are not necessarily aware but which are essential for the file.

The repression of international crimes serves both to ensure that our country is not a sanctuary for criminals and to ensure that justice is done, not in the name of the French people but in the name of humanity.

Given the low number of trials in France, what you call "the repression of international crimes" in your book, does it work, or is it a utopia?

We don't have enough hindsight yet. In France, we have had only six trials. Of the six, three involved crimes committed in France - Paul Touvier, Maurice Papon and Klaus Barbie - and three involved Rwandans. I think the French can accept a lot of things, but they will never accept that we have people operating on our territory when we know that they have committed the unspeakable in their country. The repression of international crimes serves both to ensure that our country is not a sanctuary for criminals and to ensure that justice is done, not in the name of the French people but in the name of humanity. This is what seems to me to be of capital importance. The objective of the book is a bit like that, it's to get out of daily politics and say take notice that this relationship to the rest of humanity is also important.

Interviewed by Franck Petit, JusticeInfo.net.

ÉRIC ÉMERAUX

Éric Émeraux, a colonel in the French gendarmerie, headed the Central Office for the Fight against Crimes against Humanity (OCLCH) for three years before retiring on August 1, 2020. Previously, he served as Internal Security Attaché in the International Cooperation Department of the French Embassy in Sarajevo (Bosnia and Herzegovina), after a career as a judicial investigator in the French Gendarmerie. He is the author of "La Traque est mon métier, un officier sur les traces des criminels de guerre" (Plon, September 2020). Under the pseudonym of Mathias Ka, he is also a composer of electronic music.