Nearly 200 days of delay and four false starts. Expected for years, initially scheduled for April 14, postponed to June, then August, then November, the trial of Alieu Kosiah, a former Liberian warlord of the first civil war in the 1990s, should finally begin this Thursday, December 3. Delays that have put the federal criminal court of Bellinzona, in Italian Switzerland, on edge, which only announced this last date one week in advance. Limited by the health restrictions linked to the Covid-19 pandemic but also pressed by the pre-trial detention of the accused, which has exceeded six years, the court decided to deal with the urgency and to split the trial in two parts. From 3 to 11 December, it intends to deal with pre-trial legal issues and then to hear the accused himself. The testimonies of witnesses as well as the pleadings will hopefully take place in February 2021.

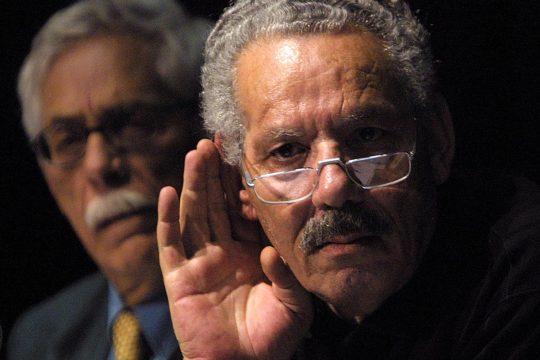

Imprisoned since 14 November 2014, Alieu Kosiah had been in Switzerland for twenty years when he was arrested. Based on the testimonies of victims of the Liberian conflict who filed a complaint in Switzerland, the Swiss Public Prosecutor's Office accuses him of having "committed himself or (...) ordered his troops to commit during the years 1993 to 1995, in Lofa County, in particular the murder of civilians, rape and acts aimed at enslaving and terrorising the population".

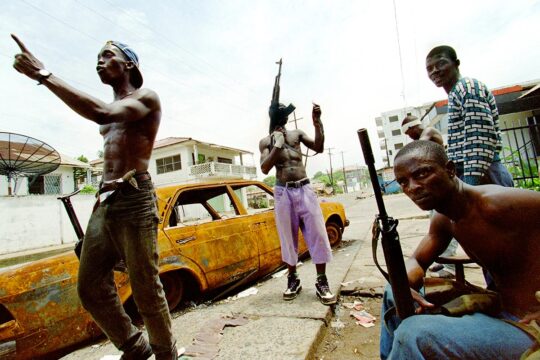

A commander in the midst of a bloody civil war

Between 1989 and 1996, the first civil war raged in Liberia. It caused the deaths of more than 200,000 people. Persecuted by the forces of the main rebel leader Charles Taylor, the Mandingo community decided to take up arms to defend itself. They founded a sub-branch of the armed group Ulimo (United Liberation Movement of Liberia for Democracy), called Ulimo-K. The son of a businessman, Alieu Kosiah had fled to neighbouring Sierra Leone at the age of 18 after members of his family were brutally murdered. He soon joined the Ulimo-K and rose through the ranks to become one of its commanders.

He was in this position when numerous massacres took place between 1993 and 1995 in the Lofa region of northern Liberia on the border with Guinea. Inter-ethnic violence continued until the election of Charles Taylor as president in 1997, which marked the end of the first civil war. It was then that Alieu Kosiah decided to leave his country. A year later, he arrived in Switzerland as an asylum seeker. From the outset, he presented himself as one of the leaders of a former rebel group. This transparency did not convince the Swiss authorities, who refused his asylum application. It was his meeting with his future wife, a woman from Vaud, that enabled him to obtain a residence permit and to do odd jobs. For almost twenty years, he lived a peaceful life. Until the Swiss NGO Civitas Maxima, having learned of his presence in the country, collected the testimonies of several Liberian victims and, in the summer of 2014, filed criminal complaints on their behalf with the Federal Prosecutor's Office.

A hero for the Liberian Mandingo people

Alieu Kosiah declares himself innocent. His lawyer Dimitri Gianoli does not deny his involvement as commander of Ulimo, nor his position as deputy chief of police in Liberia in 1995, but he excludes any involvement of his client in war crimes.

Alieu Kosiah is both the first Liberian suspect to be tried for war crimes in a court outside Liberia, and the first to be tried in a civilian court in Switzerland. (Previously, these cases were heard by military courts.) Yet he remains very popular within the Mandingo community. Like many of his Mandingo compatriots, the president of the Liberian community in Switzerland, Morisara Doumbia, sees him as a hero.

Crimes against humanity?

This week in Bellinzona, Kosiah's defence is expected to vehemently fight back the lawyers for the civil parties. They want the charges to be qualified not only as war crimes but also as crimes against humanity. The prosecutor's office believes that since the events took place before the entry into force of an amended criminal code in 2011, the charge of crimes against humanity cannot be retained. The civil parties, who have so ardently desired the opening of this trial, also wish to request the postponement of the accused's testimony. The victims' lawyers are very upset by the court's decision to have decided, at the last moment, to cancel the victims' travel from Liberia for the first part of the trial, preventing them from participating.

"We have an ambivalent feeling," said Romain Wavre, one of the lawyers of the NGO Civitas Maxima. "We are torn between satisfaction at the opening of the trial of Alieu Kosiah, whose crimes were denounced many years ago, and frustration that the court did not allow the plaintiffs to take part in the beginning of this trial they have been waiting for so long. »

The slow train of Swiss justice

This ambivalent feeling is certainly shared on the side of the Public Prosecutor's Office of the Swiss Confederation, which has been without a chief prosecutor for the past three months. It is, in fact, one of the unfortunate contenders for this post, the public prosecutor Andreas Müller, who will be in charge of leading the prosecution in the Kosiah trial. Judged too soft by the parliament's judicial committee to lead the federal prosecutor's office, Müller is the sole survivor of the original team of the War Crimes Unit established in 2013, where he picked the Liberian case. The procedure was complicated by the inability of the Swiss authorities to travel to Liberia - unlike other European prosecutors' offices - and by the limited material evidence available. It took five years for the prosecution to hear 25 witnesses and complete the indictment.

This slowness reflects a broader problem. Switzerland's universal jurisdiction and the dozen or so complaints still pending were never among the priorities of former chief prosecutor Michael Lauber, who considered these cases to be both too complex and unattractive to the general public. For NGOs and Liberians, the stakes are high.

"This trial is very important for the victims because no one has ever been convicted in our country for atrocities committed by different military factions during the civil war," says Hassan Bility, director of the Liberian NGO Global Justice and Research Project, the local partner of Civitas Maxima. A situation that, in his eyes, is beginning to change. "Many parliamentarians running for the December 8 elections in Liberia have made it a campaign issue because of the strong popular demand for the establishment of a war tribunal in Liberia," Bility said.

What is taking place in Bellinzona from this December 3 may therefore not stay in Bellinzona.