The woman seems to have become old and small from crying, sadness and unfinished grief. But her request is still the same. It is the one she made on 17 November 2016, when she testified publicly before the Truth and Dignity Commission (IVD), a commission of inquiry into state violence in Tunisia. She repeated it on 29 May 2018, when she was heard by the specialized transitional justice chamber in Gabes, 405 km south of Tunis, where the first trial serious human rights violations linked to IVD investigations was opening.

"I would like this court to allow me to find my husband's remains so that I can honour him with a dignified funeral," said Latifa Matmati, Kamel Matmati's wife, on Tuesday 25 May in Gabes, during the ninth hearing of this dark case of voluntary manslaughter, torture and enforced disappearance.

Thirty years have passed since the crime and already three since the beginning of this trial. A double anniversary that prompted some of the Tunis-based associations defending transitional justice to undertake a journey to the court in Gabes. The aim was to show their support for the Matmati family and to speed up a judicial process fraught with obstacles. When they got there they also found former President of the Republic, Moncef Marzouki (December 2011-January 2014), who signed the Tunisian law on transitional justice, who also came to attend the trial.

Convicted although dead

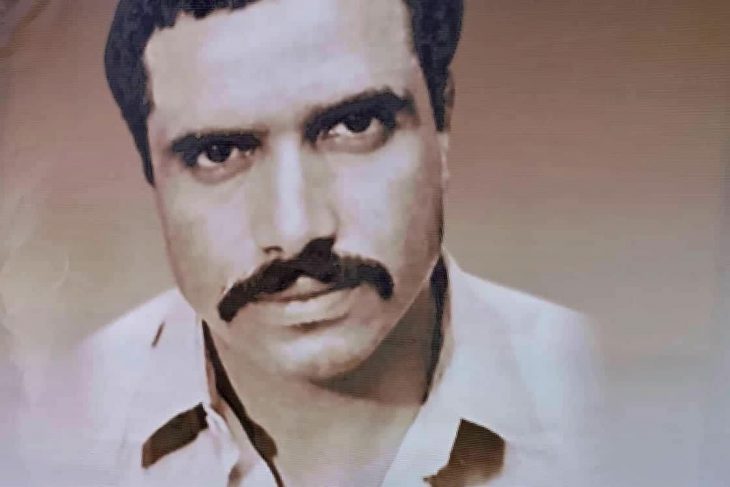

The facts date back to the time of the great raids of the Ben Ali regime against Islamists. Kamel Matmati was 27 years old, an activist of the Islamist movement Ennahdha, working and living in Gabes. On 7 October 1991, at his workplace at the Tunisian Electricity and Gas Company, he was brutally arrested in front of several of his colleagues. He never reappeared.

In 1992, Matmati was sentenced to 17 years in prison in absentia, even though the courts knew he was dead. His mother and his wife then scoured the prisons of the Republic in search of him, until 2009, when cellmates confirmed the death of the young activist. A judicial enquiry was opened in 2012. It was quickly closed due to the statute of limitations. In 2016, the State, following a demand from the IVD, finally admitted the death of Kamel Matmati and issued a death certificate to his family. On the night of 7 to 8 October 1991, in Gabes, teams of special services had taken turns to subject Kamel to the worst abuses in the police station: violent beatings, the so-called roast chicken position, hanging crosswise from the windows... All this in front of other political prisoners, who have become precious witnesses today. Kamel died under torture, from internal bleeding in the hours following his arrest.

Crucial confessions in court

"I have never said the word 'dad' before because he is nowhere to be found. I would like to do it finally in front of his coffin!" said Aicha, Kamel's daughter, five months old at the time of her father's disappearance, at the hearing in May 2018. In three years, the specialized court has heard from all members of the Matmati family. Several other witnesses have appeared before the chamber, including Ali Amri, a doctor who was tortured alongside Matmati and who was able to diagnose his death, as well as other detainees tortured in that month of October 1991 in Gabes.

On 11 June 2019, the former Minister of the Interior, Abdallah Kallel, whose name appears among the twelve defendants, testified before the chamber presided over by Judge Habib Ben Yahia. He apologized to the victim's mother while denying any complicity in the crime. On 28 January 2020, during the eighth hearing of the trial, Samir Zaatouri, one of the alleged perpetrators and former director of the special services in Gabes, openly accused two agents of the investigation services - Anouar Ben Youssef and Riadh Chabbi - of having tortured the Islamist activist. "The one who dealt the final blow to Matmati is Ali Boussetta, their hierarchical leader," he added, denying having given the order to kill Matmati. These crucial confessions confirmed the IVD's investigation report.

Delays and impunity

Sixteen months have passed since this hearing before everyone returned to Gabes. Mokhtar Jemiî is probably the most poignant of the ten or so civil party lawyers who have come to plead. "I was Kamel Matmati's prison companion, where his torture was used by the police to terrorize us. I followed the ups and downs of his case when I was a law student. I was very disappointed when in 2012 his torturers were released because of the statute of limitations," he says. He urges the president of the chamber to speed up the proceedings for due process. "Who will be left alive among the defendants, the victims and even the lawyers if more than a year goes by between one hearing and the next?" he said. "One of the main actors of the crime has just gone abroad and come back with impunity, without any travel ban being imposed on him at the airport!" He asked for execution of the arrest warrants against the defendants, as well as the issuance of an order to sequester the defendants' property - a means of pressure, he said. "What have you done with our successive requests to send an investigating judge to the Internal Security Forces hospital in La Marsa, the last place before Matmati's body vanished forever, to check the data in the register listing the patients' entries and exits? Would it be such an impossible mission for you?" the lawyer asked.

The lawyer Oula Ben Nejma, former head of the IVD investigations commission, was part of the trip to Gabes. She recalls: "During our mandate, we summoned and heard more than 30 people linked to the murder of Matmati. We have mastered all the ins and outs of this case and even have very credible leads on the place where the body was buried. We chose to send this case first to the specialized chambers because of its emblematic dimension and also in order to push the public authorities to introduce a provision on the crime of enforced disappearance in the Tunisian Penal Code."

Enforced disappearance, a phantom crime

This crime is among the serious human rights violations detailed in Article 8 of the Law on Transitional Justice of December 2013. In 2011, a few months after the revolution that toppled the Ben Ali regime, Tunisia also signed the Rome Statute creating the International Criminal Court, as well as the International Convention on Enforced Disappearances. Since then, however, nothing has been done to harmonise national law with these international treaties.

On 8 February, four UN rapporteurs, as well as the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances, wrote to the Tunisian government to express concern about the blockages in the transitional justice process. Among their criticisms is this "lack of clarity" in the law. Faced with this legal gap, the IVD had, in its investigation report, translated the offence into five existing crimes in the penal code: torture, first-degree murder, illegal confinement and detention, concealment of the corpse before it is seized by the authority, and clandestine burial of a corpse. But this does not satisfy the rights of the victims.

The IVD explored the records of the Internal Security Forces Hospital matching the dates of entry and exit of Matmati's body. It discovered a name erased with a correction pen. Their investigations lead the IVD to suspect that the body had been taken out by the agents of La Marsa and buried somewhere in the municipality's gardens. Oula Ben Nejma paid a courtesy visit to Judge Habib Ben Yahia before the start of the session. She confided that the president of the chamber has serious leads as to the place where the corpse was buried clandestinely. But she did not say whether this lead intersects with that of the IVD. For the time being, Latifa and Aïcha Matmati are waiting and continue to plead tirelessly.

SEIZING PROPERTY, COERCING THE ACCUSED

To the great joy of the lawyers of the civil party in Gabes, the representative of the public prosecutor's office will in turn present to the court the same request as the defence: to freeze the property of the accused, who have been absent since the opening of the Matmati trial. It was the Court of First Instance (TPI) of Nabeul that first took this initiative, on 30 April, in the trial of Bessma Baliî, an Islamist opponent who was tortured and sexually assaulted following her arrest in the autumn of 1991. The Tunis Court of First Instance, which handles 61% of the cases of serious human rights violations investigated by the Tunisian Truth Commission, initiated the same procedure on 20 May.

This measure gives a lot of hope to activists and associations supporting the transitional justice process, which suffers from lack of political will, multiple blockages and "global reconciliation" projects at the government level. "At each hearing, the victims are present but the benches of the accused are always sparse, when they are not simply empty," criticizes a report entitled "Assessment and Prospects of the Specialized Chambers", presented in December 2020 by a group of national and international NGOs, including the Association of Tunisian Magistrates, Lawyers Without Borders and the World Organization Against Torture.

According to the same report, such absenteeism and the inability of the judiciary to enforce warrants is the result of the proximity between the accused and those who are supposed to guarantee their presence at trials. "The former are mostly members or former members of the security forces, including the prison administration. The latter are judicial police officers, also members of the security forces. The relationship between the judicial police officers and the accused seems to be marked by a deep corporatism and a certain community of allegiance," the authors point out. These same NGOs hope that the sequestration of the defendants' property will change the situation.