For a soldier like Major Bernard Ntuyahaga, the reflexes of war probably never go away. The former soldier prefers to meet his visitor at high noon, in the open, in full view of everyone, on the main road to the international airport of the Rwandan capital Kigali. A big cap covers his head and a pair of large glasses hides almost half his face. Weighing in at almost 70 years old and 90 kilos, the plump man walks straight ahead, eyes fixed. He scans the location around him. "But we already know each other from Mutobo!" he exclaims while we are still fifty metres apart.

A smile appears on his thick lips, in a mixture of interest and concern. What do they want with him, after more than two years of calm and incognito? During his stay at the Mutobo camp - an obligatory passage in northern Rwanda for the demobilization and reintegration of ex-combatants - he drew a lot of attention from the media, most of whom he turned down. "We just wanted to know if you are alive and well and how you are rebuilding your life," we explain. For this interview, Ntuyahaga chose the store of a former army classmate. "As you can see, I am alive and well, breathing the unpolluted air of my country in perpetual spring!" he replies, before sinking into a deep silence.

Time in the “corridors of death”

After his June 2018 release in Belgium, Ntuyahaga spent six months in a closed centre for asylum seekers and candidates for deportation. After all his appeals were rejected, including before the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), his forced return to Rwanda then became inevitable. For his daughter Bernadette Ntuyahaga, this meant death and "inhuman and degrading treatment", so much so that, she told the press, "I prefer that he be killed in Belgium rather than there. [...] That way, we can at least visit his grave”.

Today, Ntuyahaga is at pains to justify such apprehensions. For him, a decision to deport an asylum seeker to the country he fled is never a pleasant moment, after a quarter of a century in exile. "Especially with heavy charges against me related to the genocide," he explains, his eyes fixed on an imaginary point.

And he remembers the eight-hour flight from Brussels to Kigali. Towards death! "I worked out three scenarios in my head that I could face when I arrived in Rwanda," he says. The first and "most likely to me": a kidnapping followed by execution, upon arrival at the airport in Kigali. The second: arrest and detention in Kigali prison, awaiting a possible trial. For this purpose, a lawyer was even there upon his landing. Finally, the third, "to which I gave little credit": reception in a process of reintegration, respecting agreements between the ECHR, Belgium and Rwanda, according to which he would not be prosecuted, once he arrived in Rwanda, for the same crimes for which he had been sentenced to 20 years in jail in Belgium.

"So I lived in fear and anxiety until after my arrival in Kigali. Then I was pleasantly surprised, and still am now," he says, his face clearer, apparently reassured about the direction the interview is taking. When he arrived, he recalls, a general from the Rwandan Demobilization and Reintegration Commission (RDRC) was waiting for him, in a scenario that Ntuyahaga had thought most unlikely. The RDRC had come to organize his stay of a few months in a reintegration centre, along with other former soldiers expelled from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Civic education and “detoxification”

Once in the Mutobo camp, they were given civic education courses, "designed on Rwandan realities and designed to detoxify us," says the former Rwandan Armed Forces major. At the end of their stay, they were trained in "income-generating activities" related to agriculture and livestock, small business and services. Then he received a Rwandan identity card, like any other citizen. With this card, he was able to access a health insurance scheme that allowed him to have cataract surgery, he explains.

Ntuyahaga had built a house around 1993, in anticipation of a likely demobilization. After the genocide, this house, managed as abandoned property, was sold to a police officer and the money paid into the public treasury. After his return, the RDRC helped him launch a recovery procedure with the Ministry of Justice. It was decided that the proceeds of the sale should be paid to him by the Ministry of Justice, upon presentation of a marriage certificate and a power of attorney duly signed by his wife, who is the co-owner of the house, according to Rwandan law. Ntuyahaga is still waiting for this payment and wonders whether, with her status as a political refugee in Denmark, his wife can contact the embassy of the country she fled to establish the required official document.

Yesterday’s enemies now “brothers in arms”

Chez Manu, two hundred metres down the road from Kigali airport, offers a relaxing and convivial meeting place for Ntuyahaga and the daily regulars. The atmosphere here is one of joy. And as long as Covid-19 restrictions allow, the beer flows. Everyone knows everyone. The youngest is in his forties. It is a meeting place for the village's old people who, seen in the mirror of the past, are both Hutus and Tutsis. Better still, there are retired members of the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA) and others from the ex-Rwandan Armed Forces (FAR) who fought against each other in the war from 1990 to 1994.

They have chosen a game that brings people together, the traditional Rwandan game called Igisoro, which pits two opponents against each other and is played by taunting each other to discourage the less valiant. On this day, Ntuyahaga has not yet played, but he challenges some of the players and praises another, an RPA elder, whom he invites to join them through a video call on his smartphone. Everyone speaks at the same time to sing their own praises. It's a real playground, improvised by Ntuyahaga, which would surprise many of those he left behind in Belgium who cried on the day of his expulsion. "What I have found here is wonderful: the politics of unity and reconciliation. Even yesterday's enemies now consider themselves brothers in arms," says the former major, who also talks about "childhood friends, school friends and rare former comrades in arms, helping me re-learn living together”.

The man who kept turning himself in

Ntuyahaga has had an extraordinary journey (see box). Wanted after 1994 by Rwanda and Belgium, indicted and then released by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), imprisoned for four years in Tanzania awaiting an extradition order, released and preferring to surrender to Belgium, he was finally convicted for his role in the assassination of Belgian paratroopers on the first day of the genocide against Tutsis in Rwanda. His descriptions of the net tightening around a Rwandan fugitive in Congo and Zambia, his flight to Tanzania and his surrender to the ICTR, his years of imprisonment in Tanzania under the eye of the Rwandan intelligence services, then his surrender and transfer to Belgium, are worthy of a Hollywood thriller. His was a 20-year journey, from his first surrender to the Tanzanian authorities in 1998 to his release by Belgian justice.

"Looking back, how do you see your experience at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and in Belgium?” we ask. "This judicial journey was physically and mentally painful but intellectually rewarding," he replies, laconically.

The “scapegoat”

Ntuyahaga doesn't like to talk about his trial in Belgium, except to say that "they needed a scapegoat for what happened”. He remembers that one of the lawyers for the civil parties considered him, the little major, as one of the "four musketeers" of President Habyarimana's regime, along with the much more famous Colonel Théoneste Bagosora, Major François-Xavier Nzuwonemeye and Captain Innocent Sagahutu, all of whom were convicted of genocide by the ICTR.

"Do you have any regrets, regarding what happened?" he is inevitably asked. He becomes thoughtful, evasive. "In a person's life, there are ups and downs, and so it is in mine," he starts, before elaborating a bit. "What Rwandan, Hutu or Tutsi, has not had their share of suffering from bad governance? Who, for different reasons and at different times, has not lost a family member or been a refugee? With this simple reading of the past, it is time to sit down together, to root out the imported evil and recover our true unity."

"And how do you see yourself now?" we ask. The former ex-FAR major says he is still "listening to people, to information, for possible opportunities". He says he has plans and should join existing structures "like cooperatives." But he is now looking forward to the conviviality of his friends over a beer and a game of Igisoro.

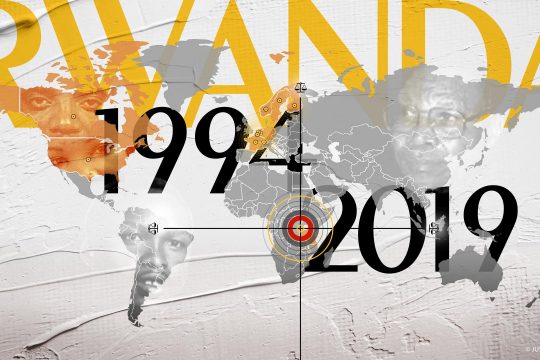

MAJOR NTUYAHAGA’S JUDICIAL ODYSSEY

- 7 April 1994. Lynching of 10 Belgian UN peacekeepers at Camp Kigali. Bernard Ntuyahaga, after dropping them off at this military camp, allegedly spread the rumour that they were responsible for the attack on President Habyarimana the previous evening.

- July 1994. His family crosses the border and settles in Bukavu, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo).

- October 1995. Following insecurity and an arrest warrant issued against him by Belgium, he leaves Zaire and settles with his family in Lusaka, Zambia.

- 6 June 1998. Fearing that he would be "kidnapped by the Kigali regime," Ntuyahaga "surrenders" to the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), based in Arusha, Tanzania. The ICTR Prosecutor draws up an indictment against him for genocide and crimes against humanity. Ntuyahaga pleads not guilty.

- 29 March 1999. Ntuyahaga is released by the ICTR after the prosecutor, frustrated that the judges had not retained the charge of genocide, dropped the case against him. Ntuyahaga went to the Belgian embassy in Tanzania, where he failed to negotiate his surrender. At the end of the day, he was arrested by the Tanzanian police for "illegal entry". Ntuyahaga was imprisoned in Dar Es Salaam, where extradition procedures were filed against him by both Rwanda and Belgium.

- March 2004. Released from jail, Ntuyahaga flies to Belgium – because, he now recounts, “I had to choose the lesser of two evils” – accompanied by a Belgian diplomat.

- 19 April 2007. Trial begins before the Assize Court in Brussels.

- 4 July 2007. Ntuyahaga is found guilty of killing 10 Belgian peacekeepers and an unknown number of civilians. He is sentenced to 20 years in jail.

- May 2018. He is released.

- 21 December 2018. Expulsion to Rwanda.