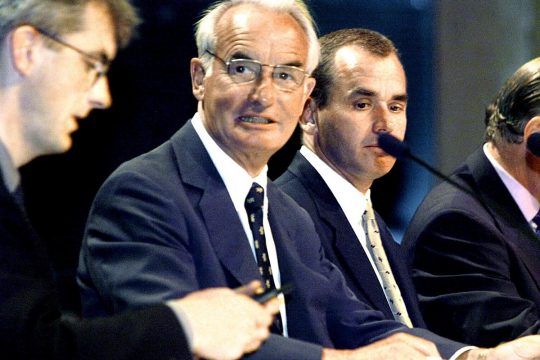

It is a first in Sweden, applauded by human rights activists for corporate responsibilty. On November 11, two Swedish executives, Ian Lundin and Alex Schneiter who were president and director of Swedish oil company Lundin at the time of the events, were indicted for "complicity in war crimes".

“The impact of a company’s activities in a war zone and the accountability of its representatives have never been part of a criminal case in Sweden before,” says Göran Hjalmarsson, a lawyer representing 13 victims in this case. This is because "many corporations look at human rights as a source of risk that must be managed, instead of a norm that must be upheld", Egbert Wesselink, spokesman for NGO PAX and co-author of the “Unpaid debt” report that sparked the initial probe, said in an interview with Reuters.

New oilfield, new atrocities

In 1999, Sudan had been ravaged for years by a war between South Sudan – which obtained independence in 2011 – and the government of Omar Al-Bashir in Khartoum. Lundin Oil had been prospecting for oil in a southern area called Block 5A for three years. “This area had been relatively spared from the effects of the civil war,” notes prosecutor Henrik Attorps, who is leading the investigation, but then became “one of the worst affected areas” after Lundin discovered an oilfield.

“In this case, the war crime itself was perpetrated by the Sudanese military and its allied militias,” Attorps explains. “For four years, until Lundin Oil left in 2003, they led systematic attacks on civilians or at least indiscriminate attacks, in violation of international humanitarian law.”

The aim was to control the area. Attacks included bombings, shooting at civilians from helicopter gunships, burning villages and their crops. “Consequently, many civilians were killed, injured and displaced from Block 5A,” the prosecutor continues. The precise number of casualties directly related to these events is not recorded, but PAX's Unpaid Debt report estimates that several thousand people were killed by the fighting or by hunger due to the destruction of crops, and some 200,000 people were forcibly displaced.

The chairman of the oil company, Ian Lundin, and the director at the time, Alex Schneiter, were complicit in these crimes by asking the Sudanese government to secure the area, says the prosecutor. “These two representatives had a decisive influence over the company’s activities at the time and were also the ones who had the crucial contacts with the Sudan government,” he explains. By presenting Khartoum with oil exploration projects in an area that the army did not control, or by making agreements with the government to build roads, the executives of Lundin Oil “knew or at least were indifferent to the fact that the military, to secure their activities and take control over this area, would have to fight, and the way they fought involved illegal warfare,” continues the prosecutor.

In addition to the criminal charges against the two executives, the Attorps prosecution team is requesting that SEK 1,391,791,000 (approximately 136 million euros) be confiscated from the company, which is the current value of the profits from the 2003 sale of Lundin Oil's operations in the area to the Malaysian company Petronas Carigali. “In Sweden, we do not have corporate criminal accountability,” says Attorps, “but when somebody or a company makes a profit because of a crime, this profit can be confiscated, along with any increase in value, as a forfeiture.” This forfeiture is not specifically demanded for reparations, which could be independently requested by civil parties at trial.

An 80,000 pages investigation report

Lundin Oil - now called Lundin Energy - immediately reacted to the indictment with an emphatic denial. “This case is both unfounded and fundamentally flawed,” said the company’s current director Nick Walker in a communiqué. “There is no evidence linking any Company representative to the alleged primary crimes in this case and we see no circumstance in which a corporate fine or forfeiture could become payable given this fact.”

Hjalmarsson disagrees: “I have been following this case for the past seven years and, given that it is an extremely big case, they wouldn't have prosecuted if they didn't have very firm grounds.”

The preliminary investigation report, which totals some 80,000 pages, gathers accounts from victims of the conflict in the area, interviews with experts but also with internal company witnesses, Attorps says. When the Swedish investigators visited Sudan and South Sudan in 2013, they were unable to gain direct access to the Block 5A area due to ongoing conflict. “Nevertheless,” the prosecutor continues, “regarding the complicity, the company handed over some internal documents at the beginning of the investigation and we made a search and seizure at the company where we seized a number of documents, including internal communications as well as communications with the government of Sudan”.

In all, some 30 victims - most of them abroad or living in the region's refugee camps - are expected to join as civil parties in the future trial. The trial is expected to begin in mid-2022 and last more than a year. "It will probably be the longest trial of its kind in Sweden, with at least 175 court days," says lawyer Hjalmarsson. The two defendants, Lundin and Schneiter, who currently reside in Switzerland, face possible life sentences.