JUSTICE INFO IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS

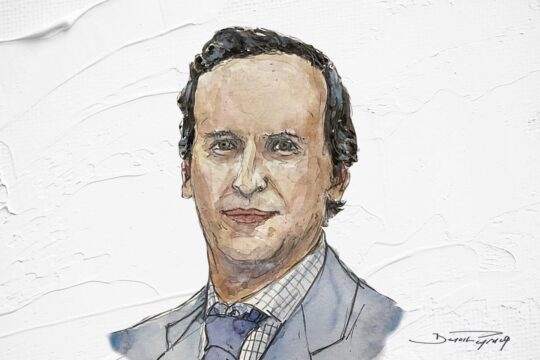

Antoine Garapon

President of the Independent Commission on Recognition and Reparation for sexual crimes committed in French religious congregations

The work of the Independent Commission on Sexual Abuse in the Church (Ciase) has caused an earthquake in French society and within the Catholic Church. Magistrate Antoine Garapon was a member of this Commission. He is now in charge of one of the two reparations bodies set up by the Church. For him, restorative justice is a way for victims to re-appropriate their history.

JUSTICE INFO: What was your role in the Independent Commission on Sexual Abuse in the Church (Ciase) in France?

ANTOINE GARAPON: I was in charge of one of the four working groups of the Commission, the one concerning the victims, with Alice Casagrande [an expert on ethics and prevention of abuse]. The other three groups dealt with canon law and legal issues; theological questions and the evaluation of listening groups by the dioceses. The victims did not spontaneously trust us: they were suspicious at first because the bishops had "taken them for a walk" so much that they feared nothing would change with this Commission. It took us a few months to gain our legitimacy in their eyes and for us to constitute a "mirror group" composed of victims representing as much as possible the diversity of their sensitivities, especially in their relationship to the Church: all our decisions and analyses were shared with them. We never ceased to keep in mind that they have "experiential knowledge", that is to say a unique knowledge about what they have experienced, which is inaccessible to us.

How has this "experiential knowledge" been useful to you?

This is the idea that Alice Casagrande brought from the medical-social field. “Experiential knowledge" is used in medicine. For example, when a person undergoes open-heart surgery for a heart transplant, someone who has experienced the same thing is there to share this very special knowledge. In judicial matters, for example, it can also be understood: the experience of leaving prison at 4am after 20 years of imprisonment for a crime is not shared until it is experienced.

This was very important for us because we quickly realized that the victims would bring us to truly understand our mission and what it was all about. We soon realized that sexual abuse in the Church was not just a problem of a few black sheep but a much deeper issue. We learned this from the victims.

That is why we have taken care to punctuate the report with victims’ stories. The book "From Victims to Witnesses" was conceived as a "memorial of words", based on the testimonies received, to begin to repair the damage.

The role of writing, of listening, of speaking is very important. Some victims came to us looking for some sort of verbal validation of what they had experienced, to give the reality of the crime a social form."

So testimonies are already a form of reparation?

One victim told me that the book brought a "resolution of rape through writing”. As if the rape was a tear in the narrative of his life, an attack on his ability to speak, and that talking about it would repair what he had experienced. The role of writing, of listening, of speaking is very important. We tried to respond to this by publishing this report and this book.

As a children's judge, I have dealt with many cases of sexual abuse involving children who were abused or for whom there were suspicions of abuse or mistreatment. In Ciase, I saw the same people again, but 50 years later, that is to say raped at 10 or 11 years old, whose lives were devastated and who could only talk about it 40 years later. Their lives were destroyed by an initial abuse that devastated them and they never recovered. Some victims came to us looking for some sort of verbal validation of what they had experienced, to give the reality of the crime a social form.

Many of them managed to overcome this, but most of their life's energy was devoted to fighting against the symptoms they experienced: the inability to love, to be touched... When we published "From Victims to Witnesses", I received almost every day absolutely heartbreaking letters that confirmed to what extent the words of witnesses and the listening of the members of Ciase had been in themselves restorative.

Reparation does not only repair the acts themselves, it also repairs a culture that made such crimes possible with virtual impunity. It is the fact of finally talking about it, 50 years later, that provides reparation.

This non-state commission, similar to a truth commission, is in many ways a transitional justice process. What were its "political" objectives?

Ciase was a commission of inquiry to establish the reality and extent of a massive crime, not a mass crime. Then there was talk of setting up reparations commissions, one for victims of diocesan priests and another for victims of priests from congregations. This is where this dimension of reparation comes in. Reparation does not only repair the acts themselves, it also repairs a culture that made such crimes possible with virtual impunity. It is the fact of finally talking about it, 50 years later, that provides reparation.

I often draw parallels between transitional justice for mass crimes and the #MeToo cause. In both cases, dignity is restored by words. I think of Claire Nouvian, who testified that she was assaulted by Nicolas Hulot, and who said, "Mr. Hulot, face up to your crime, don't back down". This I have heard very often from victims of the Church: "Live up to what you have done." Today the Church has responded, belatedly of course, but it has done so by saying, "Yes we are responsible, yes it is systemic." These words have a restorative effect, beyond individual cases.

Can we go so far as to say that this Commission has set in motion a phase of "transition", after documenting the massive sexual abuse in the Church?

I have reservations about this term "transition" because it can be read in two ways. The weaker reading is to believe that this is a suspended moment and that we will return to a period almost identical to before. It’s like the version of American NGOs in the 2000s, who promoted "transitional justice in a kit".

What is interesting about the stronger reading of transitional justice is that there is a collapse of politics. The administrative apparatus, justice and law have been put at the service of dealing in an organized way with mass violence. This is what we saw with Nazism and apartheid, for example. For the Church, there is something that has collapsed - an institution that promises salvation and sows death. Something sacred that turns into its opposite. If we take this strong reading, it means that the term "transition" seems less and less appropriate: it is not a question of finding oneself as before, but of returning transformed by the lessons learned from collective violence and crime.

The report shows that most of the cases are time-barred. Sexual abuse in the Church is the 'perfect crime'. It's a crime without a trace."

What do these revelations about the scale of the crimes and the failure of the justice system to act on lawlessness in the Church inspire in you?

The report shows that most of the cases are time-barred, because sexual abuse in the Church is the "perfect crime". If a 40 or 50-year-old priest rapes a ten-year-old boy, and we know that it takes 35 years before he can speak out, well when he does the priest is in most cases dead or very old. So it's a crime without a trace, all things being equal of course: the facts are not always present in the memory of the victims, but the consequences are visible to them.

The judicial system is not the only one responsible because, in many cases, we realize that it was a whole society that covered up for the priests, not only the Catholic hierarchy but also the families. Victims have told us that, as children, it was impossible for them to talk to their parents "because they adored the priest". One victim told me that she had filed a complaint with the gendarmerie, which was very courageous of her in the 1960s, and the gendarmes said to her: "But what are you saying against Father X, what nonsense you are saying about this good priest." Then 20 years later, the priest died in prison, sentenced to 20 years of criminal imprisonment. So this concerns the whole society.

Secondly, it is not only a problem of crimes being time-barred but also an imperfection of the criminal process that is at issue. If the judicial system is not up to the task, it is not only for bad reasons. Indeed, and this is the core issue, one does not convict someone without evidence. And finding evidence in a place that is by definition private, away from the eyes of others, is difficult. Consent or lack of consent is not marked on the forehead. So evidence is generally lacking for sexual abuse and is even more lacking after 40 years.

We need to treat sexual violence with different reasoning than those of criminal justice. Restorative justice is also a way for victims to re-appropriate their history."

The Ciase report underlines the role that restorative justice can play. In what way do you think it is a fundamental way to provide reparation to these victims?

Here, the concept of restorative justice plays its full role. Because we need to treat sexual violence with different reasoning and different foundations than those of criminal justice. Restorative justice is also a way for victims to re-appropriate their history. Victims of rape say that they filed a complaint, the police heard them, then lawyers took over the case, activists took over their story, and judges made nice trials. Many victims feel completely dispossessed of their history.

This is part of the revolution in thinking that needs to take place: how victims can keep control of their story. Restorative justice thus reconsiders the telling of one's suffering as a step forward. I think of people in particular who have said to me, "I don't want to hurt the Church. I want to tell the hurt that it did to me, but I don't want it to go any further."

But how to stay as close as possible to people, to their experience, to what they say?

This is a big challenge. We need to think about restorative justice that welcomes people in their singularity. Véronique Le Goaziou, a sociologist specializing in violence against women, shows that in feminist associations, the women who are militant and shout loudly in the street never go to court. They talk about others but not about themselves. This raises questions about intimacy, about owning one's own words, about tension between being and having. On the one hand, we have a justice system that is focused on having, on form, on quantification; and on the other hand, we have victims who understand their destiny not in terms of suffering but in terms of being prevented from being, which is completely different.

One should not confuse the spirit of reparative justice with its form. We start from the idea that there are several forms to invent, to co-construct with the victims."

In concrete terms, how is restorative justice implemented?

It is better to speak of reparative justice because this word "reparation" was given to us by members of the Church. And one should not confuse the spirit of reparative justice with its form. A face to face meeting between the aggressor and the victim is one form; what is sought in this meeting? Is it to humanize the victim, the perpetrator? We start from the idea that there are several forms to invent, to co-construct with the victims, which will be different each time. There is no set recipe for restorative justice, it is not at all dogmatic.

My commission will also study the question of control. A 60-year-old victim confided to me that, as a child, she would have thrown herself into icy water if her priest had asked her to."

On November 19, you were appointed by the Conference of Monks and Nuns of France (Corref) to chair an independent Commission for Recognition and Reparation (CIRR). How does it differ from the Independent National Instance for Recognition and Reparation (INIRR), created by the French Bishops' Conference (CEF) on November 8?

Corref trusted me to create an independent commission from scratch. The aim is that as little as possible should differ from that carried out by the CEF, since the idea is to work together. Until now, positions have diverged. Until the day before the end of their general assembly, the bishops said: "The Church is charitable but not guilty", whereas the discourse of the Corref was rather to say: "The Church is guilty, it has a debt of justice". The establishment of these two commissions shows that the bishops have evolved and are following the positions of Corref.

However, we do not have the same remit. Corref and CEF have appointed a different president for each of their commissions. Marie Derain de Vaucresson, a lawyer specializing in children's rights, heads the Independent National Commission for Recognition and Reparations of the CEF, and I head the second. My commission will deal with vulnerable adults, that is to say it will also study the question of control. A 60-year-old victim confided to me that, as a child, she would have thrown herself into icy water if her priest had asked her to.

Have victims already approached you in the context of this new commission?

We have already received more than 40 requests in ten days. I notice that victims ask for very different things: a face-to-face meeting with the institution to which the abuser belonged, money, to be registered in an official register of victims… The requests are completely different and our goal is to try to respect this diversity, precisely to have the most individualized treatment possible.

What experience will you draw on when faced with such a challenge?

When you have experienced human density, what happens between you and a victim during a hearing, you cannot turn down a request like this. So I will draw on those three years of experience of victim hearings at Ciase and on what I have seen in other contexts, notably before the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. What I find particularly motivating is that, for once, this is going to take place in France, between French people, in the very heart of French identity, which is the Catholic Church.

There is a special dimension for victims of the Church: the intervention of the sacred. How can these same men who groped me celebrate mass afterwards?"

Transitional justice has failed more often than it has succeeded in terms of reparations. What do you see as the criteria for success in such a mission?

The objective is to allow victims to "start again in their being", to regain the energy to be and the capacity to face the future, to build their future, whether they are 75, 45 or 20 years old, without being burdened by their past and being weighed down. So how do we know it's working? A lot of people say thank you, but there are all the people we haven't been able to reach. As the report showed, there are a huge number of victims who have not spoken out, who remain locked in their silence, depression and loneliness. So our main concern is to put things in place to reach them, to reach the very people we have trouble reaching. This is very difficult.

I met a lot of people and one in particular was close to being homeless: he was completely lost because he had been abandoned by his mother at age two, placed in a home and abused for ten years. And he had no recourse because he had no one outside that home. I can say that there is a special dimension for victims of the Church; this intervention of the sacred is very disturbing for people. How can these same men who groped me celebrate mass afterwards? There is a lack of understanding, it is scandalous. We can't get over it. It's a betrayal of adults, in the mind of a young person.

Do you feel you can do something about the causes?

It is not our job to treat the causes. But we have set up a research unit that will help us better understand and help the Church and the congregations to learn all the lessons that need to be learned. It is always easier to have perspective for us who are outside the Church than for people whose whole life is the Church. It is terrible for a bishop to denounce one of his priests with whom he has a fraternal relationship, it is terrible to look the wreckage of a congregation in the face. Perhaps our work can help find solutions.

Money is not the only thing, but it is important for the victims. Olivier Savignac, president of a collective of victims of sexual abuse in the Church, speaks of more than two billion euros. Will the Church pay?

I'm not sure it will cost that much. Many victims are elderly and money is not their major problem in most cases: what can you expect from money when most of your life is behind you? In any case, the Church says it is ready to repair, so we must believe it! The president of the French Bishops' Conference, Eric de Moulins-Beaufort, has said that he will follow the Ciase report.

This phrase 'crimes that can neither be punished nor forgiven' applies quite well to these crimes. We cannot punish them because of the statute of limitations but we cannot forgive them, so what can we do?"

Do you consider these crimes to be among those that can “neither be punished nor forgiven", as you wrote in a book published twenty years ago?

Yes, it's funny you say that, because I was thinking recently about that title I chose, which is not mine but Hannah Arendt's. This phrase "crimes that can neither be punished nor forgiven" applies quite well to these crimes. We cannot punish them because of the statute of limitations but we cannot forgive them, so what can we do? This is what I am working on.

Antoine Garapon is a former juvenile court judge, teacher, radio show host and author of some thirty books on justice and law. He was secretary general of the Institute for Higher Studies on Justice from 2004 to 2020. From 2018 to 2021, he was a member of the Independent Commission on Sexual Abuse in the Church (Ciase). In November 2021, he was appointed by the French Conference of Clerics as president of the Independent Commission on Recognition and Reparation for sexual crimes committed in religious congregations.