It took nearly seven years for the Special Criminal Court (CPS) - created by a 2015 law to try crimes under international law and serious human rights violations perpetrated since 2003 in the Central African Republic (CAR) - to announce its first trial. Starting April 19, three defendants from the 3R (Return, Reclamation and Rehabilitation) armed group will be tried before this mixed court sitting in Bangui for acts committed in May 2019 in Lemouna and Koundjili, in the northwest of the country, including "killings and other inhumane acts constituting crimes against humanity," according to the court's statement.

This first trial comes five months after the humiliating episode of the arrest and release of Hassan Bouba, current Minister of Livestock. A former number two in the Union for Peace in the Central African Republic (UPC) rebel group, Bouba is believed to be responsible - according to an investigation by the conflict-fueled money-tracking NGO The Sentry - for the November 2018 attack on an IDP camp in Alindao, 500 km east of Bangui, which resulted in the deaths of at least 112 villagers, including 19 children.

The Bouba case

By 2017, Bouba had joined the government as a special adviser to CAR President Faustin-Archange Touadéra. Later, he would have become "the interface between the UPC leadership and Bangui diplomacy," according to Nathalia Dukhan, an investigator and analyst at The Sentry. Arrested on November 19 by the CPS on several charges, including crimes against humanity for "murder, inhumane acts" and "cruel treatment such as torture," Bouba was initially taken by Central African special forces to Camp de Roux, the central prison in Bangui. But a few days later, there was a twist of fate: Bouba was exfiltrated from the prison in which he was awaiting his hearing, and taken back "by the presidential guard" to his home in the PK5 neighborhood, according to several eyewitnesses. "The unit in charge of extracting him [to bring him to court] was prevented from accessing his place of detention," the CPS said in a statement. In a context of general indignation from civil society, the Minister of Livestock and Animal Health even received, a few days later, the Order of Merit from the President of the Republic. Then he resumed his work at the Ministry... located a few hundred meters from the headquarters of the CPS.

"The Court is instrumentalized"

Interviewed by Justice Info, Jean-Bruno Malaka, spokesman for the Special Court, said that the Bouba case "demonstrated to everyone what the CPS is capable of and allowed it to register more than 261 complaints, including 107 in 2021”. But this arrest revealed above all the dysfunctions of the Court. "I am not aware of this type of interference with justice in other contexts," says Patryk Labuda, assistant professor of international criminal law at the University of Amsterdam. "The Court is instrumentalized, and the government's actions show that it doesn’t always find desirable the presence of the Court, which is supposed to be independent," he says.

Arrests "depend on the goodwill of the state," confirmed a source close to the CPS, who said that a national judge and military police in charge of arrests "have received threats from the government”. In addition to this lack of independence from the state, there are problems within the court. "The relationship between nationals and internationals is difficult to establish. In addition, Central African judges are under pressure from the government," said a source close to the institution in Bangui who prefers to remain anonymous.

Lack of transparency

It also took the CPS many years to assemble its judges. On February 2, the last two judges of the appeals chamber, Frenchman Olivier Beauvallet and German Volker Nerlich, were sworn in in Bangui. "The establishment of this jurisdiction follows a certain procedure, we have not had all the means since its creation, it took time to recruit international judges," explains the spokesman of the CPS.

The notable absences of Special Prosecutor Toussaint Muntazini, a senior prosecutor in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), have added to the weakness of the CPS. "The prosecutor has health concerns and is rarely present, which hinders investigations and proceedings," said an anonymous source close to the CPS. "The prosecutor is on leave," the spokesperson tried to reassure.

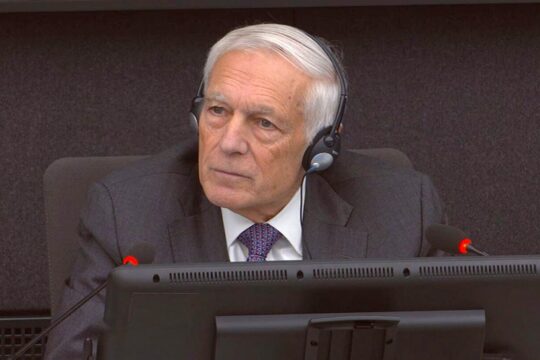

The CPS is also often criticized for its lack of transparency. In December 2021, Amnesty International denounced the court's "lack of transparency" and stated that it remained "very difficult, if not impossible, to find information on the status of ongoing proceedings”. Pre-trial detentions are a sensitive example. The court refuses to disclose the identity of its detainees, a situation unheard of in international justice. The CPS spokesman assures that there are currently "14 people in pre-trial detention" and that "nine detainees have been released for having reached the regulatory and reasonable time limit for their detention," which is one year. "Pre-trial investigations are covered by secrecy," says the president of the CPS, Michel Landry Louanga. "We are in a situation of crisis, of conflict, we have victims and witnesses who need to be protected. Publicizing the investigations puts the lives of these people in danger. In the Central African Republic, the main perpetrators of crimes are still there, in society," he said in an interview with Justice Info.

Budgetary tension

The United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (Minusca) is among the main donors to the CPS, along with the European Union, the United States, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Netherlands. "Despite the importance of its mandate, the Special Criminal Court has a relatively small budget compared to other hybrid judicial institutions that try international crimes," warned the NGO Human Rights Watch in an April 12 article, noting that "the financial situation of the CPS is complex and reflects the increased difficulties that justice efforts for serious crimes in different countries have faced in recent years when it comes to finding adequate operating resources”.

"If the European Union does not renew its funding for the coming year, the CPS will die," said a UN source, who preferred to remain anonymous, in early 2022. "The Court needs about 12 million dollars a year to function but we only manage to mobilize 6 to 8 million from scattered donors," explains this same source.

The Central African Republic, devastated since 2013 by civil war, is still experiencing a latent conflict where there are neither winners nor losers. "Despite the war, our investigators have infiltrated these [war] circles to be able to push forward the proceedings and that is a feat," reassures the president of the Court. "Usually, people work in post-conflict contexts where the perpetrators of these crimes are in a weak position, but this is different."

THE THREE DEFENDANTS OF THE FIRST TRIAL BEFORE THE CPS

Issa Sallet Adoum aka Bozizé, Yaouba Ousman and Mahamat Tahir belong to the 3R (Return, Reclamation and Rehabilitation) rebel group, one of the most powerful armed groups posing as a self-defense people’s militia. Prior to the government counteroffensive supported by Russian troops in December 2020, this group had expanded its hold over all of northwestern CAR, pocketing significant revenues from transhumance. In 2019, just after the attacks in the localities of Lemouna and Koundjili, where the 3R are accused of having massacred civilians, the leader of this militia, Sidiki Abass, had handed over to the Central African authorities and the UN these three men. They are now tried before the Special Criminal Court for murder and other inhumane acts constituting crimes against humanity, and for murder, torture and other outrages upon personal dignity, including humiliating and degrading treatment, constituting war crimes. The accused Bozizé, who was one of the group's military leaders, is also accused of rape committed by his subordinates in the commune of Koundjili.