JUSTICEINFO.NET IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS

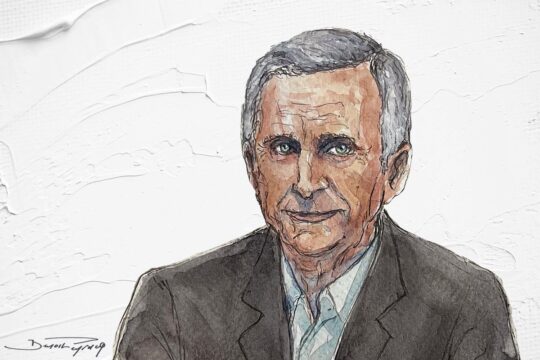

Reed Brody

Human rights lawyer

Twenty years ago, on October 16, 1998, Chilean former dictator Augusto Pinochet was arrested in London for crimes committed under his rule. For international justice it was a historical day. For human rights lawyer Reed Brody it was transforming. Years later he would be instrumental in bringing to justice another dictator, Hissène Habré, from Chad. And he is now trying to help obtain the prosecution of former Gambian president Yahya Jammeh. He reflects back on the significance and legacy of the Pinochet precedent and on what is needed to successfully bring a former head of state to justice.

JUSTICEINFO.NET: How do you remember the day Pinochet was arrested?

REED BRODY: We knew Pinochet was in London. We knew there was a case against [him]. On October 16 I was conducting a retreat for Human Rights Watch and someone came and said: CNN announced that Pinochet has been arrested in London. In the follow-up from Rome [where the conference creating the International Criminal Court took place in July 1998], we all understood what this could represent. When Judge Garzon [the Spanish judge who issued the arrest warrant against Pinochet] came face to face with this huge historical responsibility, that really changed the course of history. That evening the London police go to the home of a part-time stipendiary magistrate, like a justice of the peace, the lowest level of a Common Law judge – and that to me is one of the most beautiful parts of the story. This judge takes a form and he writes two sentences on the form, handwritten: Augusto Pinochet Ugarte is accused between the 11th of September 1973 and the 31st of December of 1983 (…) [of] the murder of Spanish citizens in Chile. That one page by a Common Law judge leads to the arrest of this dictator, a man who said ‘not a leaf moves in Chile without my knowing about it’. And here he is laid low by the simplest of a Common Law judge.

What do you mean when you say that you knew what this event meant?

This was the rubber hitting the road. This was going to be a test of international criminal law, the first real test of whether the wonderful principles we had been thinking about – Nuremberg, the Rome Statute, the Torture Convention – could actually be put into practice. Up until then history had not been very favorable to this kind of things.

This was going to be a test of international criminal law, the first real test of whether the wonderful principles we had been thinking about – Nuremberg, the Rome Statute, the Torture Convention – could actually be put into practice.

Eventually, after more than 500 days of house arrest, Pinochet went back to Chile as a free man. But you stated that it was a “wake-up call” for dictators. When did you realize that great human rights abusers sitting as heads of state may not necessarily change their behavior despite the Pinochet precedent?

It was very facile to say that this is going to change and dictators are going to quake in their boots. It made for an easily understandable argument. We know from domestic law enforcement situations that in order to have a dissuasive effect there has to be a relatively high certainty of punishment. And we are very, very far from that, even today. But this was not just any case. For people of my generation Augusto Pinochet was the iconic dictator, whose atrocities gave rise to the modern human rights movement. This is a man whose repressive tactics unleashed the very forces – human rights activists, international declarations and conventions – that would lead to his arrest twenty years later. Because of Pinochet hundreds of thousands of articulate middle-class Chileans were thrown into exile. The ranks of organizations like Amnesty International swelled both by the news of what was going on under Pinochet and by the refugees themselves. That led to the push for the Torture convention that ultimately would ensnare Pinochet. In a sense he set in motion the forces that would lead to the Pinochet case.

Pinochet died in 2006, flouting every attempt to prosecute him and escaping a trial. So what was the legacy of this event?

He died without being prosecuted but at the same time he was in every other way encircled. He left a Chile where there was no possibility that he could have been prosecuted, in which he had built a wall of immunity. When he came back he was submerged by legal cases brought against him; the truth about his crimes had come out; because of the freezing of his assets it was discovered that he had sucked away money in Riggs Bank in Washington. His arrest actually allowed the completion of the transition in Chile. It was his arrest in London, the humiliating detention for over a year, that gave Chilean society the impetus to move forward.

What about the impact at the global level?

It created this idea that justice was possible and that it could be used as a tool by activists and victims. It’s hard to overstate the effervescence in the human rights community, particularly after the first decision by the House of Lords [In November 1998, the House of Lords confirmed the legality of Pinochet’s arrest]. All of a sudden we had an instrument to bring to book people who seemed out of the reach of justice.

It created this idea that justice was possible and that it could be used as a tool by activists and victims. All of a sudden we had an instrument to bring to book people who seemed out of the reach of justice.

And so in 1999, you decided that the next Pinochet could be Hissène Habré…

Yes. In the meantime other opportunities presented themselves, but each one just reinforced to us how political this was going to be. We understood that for the Pinochet case to go forward the planets had to be in perfect alignment. Had Margaret Thatcher still been in power the British police would certainly not have executed the Garzon arrest warrant. Most other countries would have buckled before the political cost of a break with the status quo. We were aware of historical precedents: there was Abou Daoud, who was accused in the massacre of Israeli athletes in the 1972 Munich Olympics, who was apprehended in France and yet France rejected extradition requests by West Germany and Israel; it was hard to see anyone bringing Henry Kissinger to book…

What made the Habré case more promising?

What was interesting in particular about the Habré case was that he was living in Senegal, in the global South. The pushback to the Pinochet case, to the extent that there was one, was: why is it always the former colonizers who are prosecuting leaders from former colonies? We thought that if we could persuade Senegal to exercise universal jurisdiction we would really universalize the principle of universal jurisdiction. In addition, Senegal was the first country that ratified the ICC treaty. There was no immunity involved. The alleged crimes were egregious even though they were not well documented. And we were approached by the leading human rights activist in Chad at the time, Delphine Djiraibe, who said: can you help us do what Pinochet’s victims have done? This wasn’t us parachuting in.

So this is when you established your list of criteria: a request from a national NGO, the availability of evidence, the absence of legal barriers such as immunity, the independence of the judiciary in the forum country and some likelihood of success?

Exactly. We were also hoping for a case that represented a repression scenario rather than a civil war scenario, if possible.

Why?

More clear cut. Less ambiguous. And also we were hoping for a case, at this early stage, that would not be hyper political: not Fidel Castro, not Henry Kissinger. We wanted to nurture the precedent a little before putting it on the chopping block.

So an additional criteria is that the “target” has to be politically vulnerable, without the strong support of one of the major superpowers?

Yes. We wanted to broadened the consensus around the Pinochet precedent rather than immediately antagonize one side or the other.

Hissène Habré was a relatively low-hanging fruit. We wanted to broadened the consensus around the Pinochet precedent rather than immediately antagonize one side or the other.

And yet it took 17 years to have Habré tried…

That’s right. Hissène Habré was a relatively low-hanging fruit, and yet… Which illustrates the difficulty of doing this, of breaking with the international diplomatic status quo, of getting a bystander state like Senegal to muster the political will and the investment in a case that doesn’t really concern it. You need a strong link to the forum state. You need to generate the political will in the forum state.

Is there also a point where you need luck?

Luck is always part of it. For fifteen years I always felt that we were just around the corner. But yes, if president Wade [of Senegal] had stayed in power it certainly would have cast a huge doubt on everything we were doing. And Habré could have died. There are so many variables in a case like this: the attitude of the territorial state; the funding to keep this going for eighteen years – we raised five or six million dollars in the course of that time.

That’s another aspect of the Habré experience: you need a particularly strong NGO to sustain the effort.

Yes. You need a strong and transnational advocacy coalition, however you do that. In many cases, like Guatemala or Pinochet, you have a strong nexus, a strong bridge between people in the forum state and people in the territorial state. In the Habré case it was more difficult because you didn’t have people who bridged that. So Human Rights Watch and I played that bridging role. The other thing we really learned is to put the victims and their stories at the center. That’s the thing what will drive people to support a case like this. It’s not Reed Brody; it’s Souleymane Guengueng.

Your strategy is based on a partnership between local victims associations or local actors and an international Human Rights NGO. What is it that each partner brings?

In our case we were able to combine the legitimacy and the local knowledge of the Chadian victims and lawyers with the diplomatic savvy and fund-raising skills of an international organization. There were tensions, of course, but those tensions even contributed to a synthesis that took into account both the national and the international. We were constantly discussing the choice of people to put forward or even the way we were going to frame issues. There was an international and a national point of view and the synthesis of that was almost always beneficial. Who should we bring from Chad to Dakar? I would want the people who spoke good French; and Jacqueline [Moudeina, a leading lawyer for the victims] would say: it’s not fair, we have people who don’t speak French and it’s important that they feel part of the coalition. There was this constant back and forth. But also, in essence, we had hundreds of people working for us. You don’t have that when you’re going through intermediaries and just putting your toe in the water a little bit. You’re directly working in the water.

Part of what makes your success – some would say your brand – is your relentless and sophisticated use of the media. How communication fit into your work as a human rights activist and how central has it become over the years?

I see communications as a tool to create the political conditions in Senegal for the government to feel comfortable with the prosecution of Hissène Habré. I learned that the only way to do that was to focus on the stories of the victims, to create identifiable, recognizable, sympathetic leaders among the victims whom people around Senegal, around Africa and around the world, would identify with their quest.

I learned that the only way to do that was to focus on the stories of the victims, to create identifiable, recognizable, sympathetic leaders among the victims whom people around Senegal, around Africa and around the world, would identify with their quest.

The New York Times was great, and Le Monde was great, but for me it was all about Radio France Internationale, and to a lesser extent Jeune Afrique. People around Africa, around Senegal, around Chad, followed the story year in and year out. They identified with Souleymane [Guengueng, a former inmate], and Clément [Abaifouta, another former prisoner], and Jacqueline [Moudeina]. People understood how long they had fought; it became a saga, this legal and political soap-opera. Habré’s team did not campaign internationally; we had almost the monopoly in the international press. Habré’s strength was national. That’s where they had placed all their efforts. And that was much harder for us. We spent an enormous amount of effort trying to get the Senegalese public on our side.

What are the advantages and limits of universal jurisdiction?

We all agree that universal jurisdiction, like the ICC, is subsidiary. The ideal situation would have been for Hissène Habré to be prosecuted in Chad. But the conditions never existed for that. Everybody in our coalition accepted that sending Habré back to Chad was a dangerous idea. Because he could have been mistreated or killed. Because he certainly wouldn’t have got a fair trial. Universal jurisdiction was the only thing available. It was always Plan A.

The difference in the Habré case was the predominance of the victims. Hissène Habré’s trial went down almost exactly as we would have planned it fifteen years earlier. The narrative that was presented to the court by the prosecutor was the narrative that the victims had woven. Certainly the trial would have been different had Habré built a defense, but I am talking about how the charges were framed. One of the critics that can be made of all the early ICC cases is that they were framed very narrowly. Either the targets were chosen very narrowly or the charges were presented very narrowly, in order to secure a conviction or minimize political resistance.

In our case we decided from the very beginning, based on what the victims were saying, and based on the composition of the victims association, that the trial had to include all the victimized groups in Chad

In our case we decided from the very beginning, based on what the victims were saying, and based on the composition of the victims association, that the trial had to include all the victimized groups in Chad: the Muslims, the Christians, the Zaghawas, the Hajarais, the Southerners, the political prisoners, the prisoners of war. We had to figure out how to make the case manageable so that it didn’t turn into a Milosevic kind of a case. But it was always very clear that all of Habré’s alleged crimes had to be presented. In essence, the case had been built by the victims before the court even came into existence. Then, very importantly you had the institution of the “parties civiles”.

You’re coming from a Common Law system and strangely all the cases you describe as successful – Rios Montt in Guatemala, Habré, Pinochet, the Liberian cases in Europe today – seem to rely on the full participation of victims before and during trial – the “parties civiles”. What do you make of the international model which doesn’t have it?

I think it’s very difficult where you don’t have full victims’ participation. Right now I am working on the [former president of Gambia] Yahya Jammeh case. We don’t know where it’s going to end up. It could end up in Ghana, in Gambia, somewhere else. But the likelihood is that it would end up in some Common Law jurisdiction in which the victims don’t have that central role and we will have to rely on someone else. It’s going to be very challenging.

Is this a serious handicap?

Yes, it’s a very serious handicap. It makes it difficult for the legal case itself when you don’t have the direct input from the affected community. It also reduces the transformative impact of a case. I realized that on the way. I find it so unsatisfying, so backwards, not to have the victims fully represented in a case like this. One can say that these international courts are not about fighting impunity, that the purpose of a trial is to determine if the accused is guilty or not of the charges against him. But to me, cases like Rios Montt or Hissène Habré are also about transforming the relationship between the rulers and citizens.

I find it so unsatisfying, so backwards, not to have the victims fully represented in a case like this. To me, cases like Rios Montt or Hissène Habré are also about transforming the relationship between the rulers and citizens.

It's about turning the tables. It’s about Souleymane Guengueng saying at the end of the trial: “Today, moi je me sens dix fois plus grand que Hissène Habré” [I feel ten times bigger than Hissène Habré]. It’s not just about the “fight against impunity”. It’s also about the fight to say that we have the power. We have the power, if you go too far, to bring you to justice.

After the Habré trial you told me you wanted to take a break and do something else. A year later you were back in business, back to Human Rights Watch. What happened?

Well, as you know, Senegal and Gambia are very interconnected. And the whole time I was working on the Habré case people were saying: when you’re finished with Hissène Habré, why don’t you help the Gambians? It happened that just as we were finishing the Habré case Yahya Jammeh fled from power. And I was contacted by a Gambian woman whose father had been killed by Yahya Jammeh. So when we went for the final appellate verdict in the Habré case in Dakar in April 2017 we decided to go from Dakar to Banjul with Jacqueline, Souleymane, Clément, Abdourahmane [Gaye, a Senegalese survivor of Habré’s prisons], to meet with the new Gambian victims’ associations. The Chadians presented the story of what they had done and the Gambians had their eyes wide-opened. They saw what the difficulties were but they also saw that with determination and tenacity and luck and imagination, these obstacles can be overcome. So together we decided to give it a try. For me it was an opportunity to try to put in practice some of the things I have learned in the Habré case, hopefully without making all the same mistakes.

Why is Jammeh potentially a good case?

The two big challenges in the Jammeh case are that on the one hand he is in Equatorial Guinea, which is a very perfected dictatorship, less permeable to international pressure; and on the other hand Gambia today is not ready to prosecute him. It’s a country still undergoing a delicate transition where institutional, security, and geopolitical factors suggest that we wait a bit before he could be brought back to Gambia. So we have a double problem: it will be a challenge to get him out of the country where he is and where nobody thinks he should be tried; and it doesn’t seem it’s the moment to bring him back to Gambia. So we have to think about solutions. That’s why we’ve been focusing on a third possibility, which is to have him in the first instance be prosecuted in a country like Ghana.

To me timing is always a dimension in these things: to do things when you’ve created the conditions to do them. In the case of migrants [In 2005, more than 50 migrants were allegedly murdered by Gambian government forces], we have citizens of five different countries who have been killed. We believe we can ultimately create enough consensus within the region that Obiang [the president of Equatorial Guinea] might be willing to give up Yahya Jammeh. But we’re not there yet. We know the president of Guinea will oppose the prosecution of Yahya Jammeh. We have a hill to climb. It all goes back to creating the political conditions. Yahya Jammeh was not a very popular president in the region; that’s why he is not in power today.

And that’s why he is a good “target” for you?

Look, I also believe now that you have to bring cases against George Bush for torture. You have to do what you have to do and what’s right to do. But the secret to win cases is to take winnable cases, cases where you see a path for victory – and yes, Yahya Jammeh is relatively low-hanging fruit, as was Hissène Habré. I think the more you take these cases, the more you win these cases, the more you show other people that they can bring them. Particularly in Africa people are very inspired by [the case of] Hissène Habré; so you have a kind of a multiplier effect.

Yahya Jammeh is relatively low-hanging fruit, as was Hissène Habré. I think the more you take these cases, the more you win these cases, the more you show other people that they can bring them.

When we started in Chad people thought we were crazy. There was a victim who said to Human Rights Watch: “Mais depuis quand la justice est-elle venue jusqu’au Tchad?” [Since when justice has ever come to Chad?] Souleymane Guengueng talks about how people used to think he was a fool. Now when I go to Gambia people say: “He is the guy who helped the Chadians bringing Hissène Habré to justice; now he is here to help us with Yahya Jammeh.” It’s like a normal thing now. You do this. It’s no longer a crazy idea.

REED BRODY

Reed Brody coordinated Human Rights Watch’s work in the Pinochet case and was counsel for the victims of Hissène Habré of Chad and Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier of Haiti. He currently works with victims of the former dictator of Gambia Yahya Jammeh.

Picture: Reed Brody in a demonstration against former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet (date unknown)