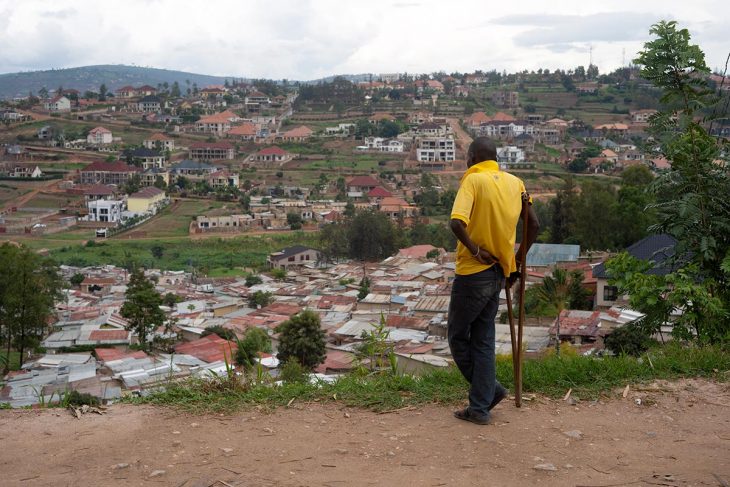

It's not easy getting to the house of mother KRA*. It can only be reached by a single tortuous path that winds its way between the houses of Mount Jali, the highest hill of the Rwandan capital Kigali whose steep slopes take your breath away. At the end of January 2020, young Maria, the alias of KRA's daughter born from rape during the 1994 genocide, walks ahead and holds the visitor's hand firmly. "Avoid looking behind you, it would make you dizzy!" she advises.

You climb, more than you walk. “Watch out for the steps!” warns Maria. These are bags filled with sand, lined up to help climb numerous obstacles, before finally reaching their hovel. It is a two-metre-by-three, leaning against an embankment from which the rainwater oozes out. One misstep and one would fall down onto the rusty roofs of the houses piled below, or crash against huge rocks exposed by the continuous erosion of torrential rains and household water. These houses, where the poor and the abandoned find themselves, were once called "birds' nests" by a mayor of Kigali and were doomed to disappear. For Mother KRA, living here was not a choice.

A grey scarf is wrapped tightly around her neck and fractured left arm, immobilizing them. Her injured right leg, as big and numb as a tree trunk, recently betrayed her while she was going down for some vital supplies. "Why did I survive the genocide?" Mother KRA whispers between sobs. Withdrawn, she no longer sees anyone and is surprised that she has now agreed to receive someone. Undermined by poverty, illness and unhappiness, Mother KRA, 53, sheds a string of lamentations every day: "Why did I have children only to suffer myself and leave them suffering? Why did I bear witness only to have genocidal Hutus convicted and be exposed to reprisals?”

A feeling of abandonment

In 1997, Mother KRA was a witness in the Akayesu case, the first genocide trial before the UN’s International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) in Arusha, Tanzania. She is one of "those brave women who broke the silence, overcame their modesty and helped history to condemn rape" as a crime of genocide, in the words of Naphtal Ahishakiye, executive secretary of Rwandan survivors’ organisation Ibuka. Rwanda was then subject to attacks by infiltrators who targeted survivors and especially witnesses of the genocide perpetrated against the Tutsis between April and July 1994. Mother KRA received several death threats. "We reserve a slow and special death for you! We are going to cut off your nose, your hands, your feet (...) and that way you will no longer accuse us," threaten the leaflets addressed to her.

The ICTR offered her a relocation to Tanzania, she says, but she could not accept this measure, which would have forced her to leave a little sister and a handful of orphaned nieces and nephews she took in after the genocide to fend for themselves. The ICTR paid her a year's rent in Kigali, the Rwandan capital. But after that, Mother KRA felt abandoned, with no alternative but to wander. "I find myself here, where I live on nothing in this cheap hole where nobody knows me." All this, she says, is "because the ICTR lied to me with its honeyed promises" of assistance and protection. And because this "solitary" survivor, who lives "on tears and nothing" no longer hopes for anything from the Rwandan state either.

Even the Victims and Witnesses Protection Unit (VWPU) at her country's Attorney General's Office did not know her and vice versa. When, by coincidence, Mother KRA found out about this unit, she met with rejection because, she was told, "she pleaded her case in the local media instead of going to see them"

“This protection is nothing but words”

Since its closure in 2015, the ICTR has been replaced by the Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals (MICT), one of whose two divisions is based in Arusha. Of the nearly 2,200 witnesses who testified before the ICTR, some 1,500 "protected witnesses" are now receiving assistance from the MICT, some of whom have passed away, according to Ousman Njikam, head of the Mechanism's external relations. Nearly 88% of these 1,500 witnesses are between 35 and 70 years old and 23% are women. They live in more than 50 countries around the world. According to the Mechanism’s website, some 995 of them are registered at the Witness Protection and Support Unit clinic in Kigali, which liaises with the MICT in Arusha. The website also states that "support for victims of sexual violence" - such as KRA - "is a key element in achieving healing and reconciliation".

But former witnesses are not complimentary about their relations with the UN structure. "They promised us the best, especially in terms of security and welfare," says TEG, who testified in the trial of Georges Rutaganda, a former national vice-president of the Interahamwe militia who was sentenced to life imprisonment by the ICTR and died in prison in Benin. "But they only worried about us before and during the hearings. Once back at Kigali airport, it was the last goodbye. Do you think they know or care where and how we are today?"

"This protection is just words, nothing but words," says bitterly KYT, a woman who testified in several trials, including that of Juvenal Kajerijeri who was sentenced to 45 years in prison. She remembers the threats and insecurity that led her to a life of wandering on her return from Arusha.

Defence witness disappears

Witness JKZ testified for the prosecution at the ICTR in the trial of former prosecutor Siméon Nshamihigo, who was sentenced to 40 years in jail for genocide. Testifying in a genocide case "puts you in a perpetual state of insecurity," he says. JKZ says he had to flee his region after threats from friends and relatives of the convicted man. But he was not alone, he says. The witness NMA, JKZ explains, had the "unfortunate idea of testifying in Nshamihigo's defence". Today, more than 20 years after NMA's testimony at the ICTR, his whereabouts are unknown. Is he still afraid of reappearing in his region of Rusizi, where the families who were victims of Nshamihigo's genocidal acts live? NMA, convicted by the national justice system and imprisoned for genocide, was awaiting his appeal at the time of his testimony. But he was later transferred, tried and acquitted by a gacaca court in his home town of Cyangugu, in the south-west of the country. When he was released, he was not only the target of a social embargo but also threats of all kinds and from all sides. His own wife, it is said, rejected him and dispossessed him of all his possessions, with the blessing of the local authorities. In his circle, it was common knowledge that he had defended the former deputy prosecutor who had become, according to the local branch of Ibuka, "one of the brains behind the genocide in Cyangugu".

“To testify for or against," JKZ acknowledges, "alienates community members according to whether they support the victim or the suspect, who in their subconscious represent good and evil respectively.

Responsibility of the Un or Rwanda?

Njikam says the UN mechanism "maintains constant contact with witnesses and relies on the cooperation of member states where witnesses reside to monitor their protection and support". For in the end who, the Rwandan state or the UN tribunal, is responsible for the protection of these witnesses? In June 2019, this question was asked at a press conference by Jean-Bosco Mutangana, then Prosecutor of Rwanda, and Serge Brammertz, Prosecutor of the MICT. They were unanimous in affirming that "for any witness who is found to be subject to threats and insecurity, protective measures are taken, which can go as far as the relocation of the witness in question".

Rwanda has always maintained that the protection of its citizens is its responsibility. Thus, witness protection is the responsibility of the VWPU, which is part of the Attorney General's Office. "Of course their security as Rwandan citizens is our responsibility," said the head of the unit, Théoneste Karenzi, "but we don't have a list of them or even know them, as we had no role in recruiting them," except for those in trials where the national prosecutor's office has played a direct role.

According to the VWPU official, there have been many witnesses in genocide trials, including those before the gacaca courts which tried more than a million people across the country, as well as those who testified in Arusha. In view of this number of witnesses to be protected, the country has opted for the "community protection" system, with a committee including the head of Ibuka in each district. According to Karenzi, the VWPU will only intervene with the Mechanism on specific issues under the direct responsibility of the Mechanism, such as witness tampering.

Moving with the wind

Naphtal Ahishakiye, executive secretary of Ibuka which has always been very critical of the UN tribunal, has come to castigate the fact that these witnesses believe the UN tribunal still owes them something. "What do they still expect from this court? Gone are the good words, the little money they were given to get them interested in testifying! They are no longer useful for anything. It got from them what it wanted, now they are no longer useful to it," he concludes.

With the confinement imposed by Covid-19, the MICT clinic in Kigali says it is thinking of its beneficiaries and HIV/AIDS patients eligible for anti-retrovirals and food support. But how to find Mother KRA, for whom Ibuka says he is thinking of a permanent relocation and with whom the VWPU says it wants to renew contact? No one knows "where the migrating bird lives," Mother KRA often says, between tears. "I'm moving with the wind," she sighed on the phone on May 20. "For me, the wind is when I'm chased away for unpaid rent, but it's also when a benefactor offers or pays me a place to live. The wind is towards poor neighbourhoods where I can find small domestic jobs. “

* All the names of the witnesses we spoke to have been replaced at their request by a pseudonym. This is different from their ICTR codename.