On July 28, the UN-backed Special Criminal Court (SCC) in Bangui, capital of the Central African Republic, handed down its verdict in the Ndélé 1 case. It sentenced six defendants in absentia to prison terms ranging from 20 to 25 years for war crimes and crimes against humanity. Twenty people have been tried by the SCC to date, including one who was acquitted (in the Ndélé 2 trial) and three definitively convicted. The trial court handed down a guilty verdict on 16 others, of whom ten were absent.

The SCC has issued 48 arrest warrants. Thirty-eight people are still wanted, 27 of whom are under investigation. Only one trial, the Paoua case, has been completely finished, with reparation measures carried out last year.

Having given final judgment in the Paoua case and given first instance judgment in the Ndélé 1 and 2 cases, the SCC still has some 20 cases under investigation. Six of these have been completed, or are nearing completion, and the court is keen to “wrap them up” before its second term expires in October 2028. A fourth trial could open shortly. But this hybrid court, made up of national and international staff, is facing financial and human resources difficulties.

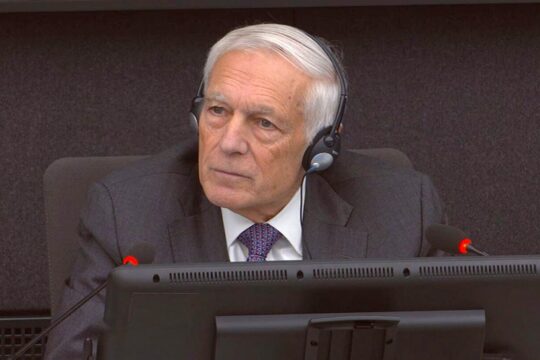

“At the beginning of the court’s existence, we had several partners supporting us,” says SCC president Michel Landry. “I don’t understand why we can’t maintain the same momentum today. Perhaps it is because of the various crises the world is going through, perhaps concerns and interests are now elsewhere. I don’t know, but the enthusiasm that existed at the start is not the same today.”

United States pulls out

Since its creation, the SCC’s annual budgets have never been fully funded. In 2023, for example, the budget was $15 million, but donors only paid half that sum. There is the same problem this year, while three cases have just been tried (Ndélé 1 and two phases of Ndélé 2), resulting in the conviction of 16 defendants. The SCC is preparing to open another trial on victims’ civil interests, with a likely decision on reparations as in the Paoua case. “Last year, to carry out the Paoua case decision, we received support from the Americans, which enabled us to proceed with reparations. Today, the coffers are empty, and we don’t know how we’re going to manage if other convictions require compensation,” worries Louanga. “We are not a court that gets specific funding from the international community like the International Criminal Court (ICC), whose funding is programmed every year. The Special Criminal Court operates on the basis of voluntary contributions from States and certain international organisations. What we receive is what allows us to operate.”

The SCC will meet its donors again in September to review its budget and prospects for completing its second mandate. Following the withdrawal of the United States, which is providing 1.9 million dollars for the 2025 budget, this will be a period of major negotiations. These will notably involve the UN Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA), whose 2025 budget starting July 1 has apparently still not been decided in New York; the European Union, which is returning after withdrawing in 2023; and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), which seems to want to leave. The UNDP does not provide money directly, but takes care of all staff contracts, equipment and supplies.

Only one trial chamber, not enough international judges

The law that created the SCC provided for it to have three trial chambers. Ten years later, it has only one. “At present, we don’t have enough international judges to do the job. There have been some departures recently. We have at least three vacancies,” Judge Louanga explained in June. Deputy Prosecutor Alain Ouaby-Békaï added: “The law provides for hybrid investigating chambers: one international judge and one national judge. Unfortunately, the mandates of the first international investigating judges expired, and the body that provides us with these judges, MINUSCA, is struggling to recruit. Today, two investigating offices have no international judges. Thank goodness we’ve just recruited some. Recruitment, redeployment of judges and the willingness of countries to make them available for the Special Criminal Court is a whole process. Recruitment can take a year or two. As a result, the only current international judge before the investigating chambers is split between the three investigating sections. This makes the work difficult.” On July 16, Swiss prosecutor Laurence Boillat was sworn in as a judge at the SCC and is due to join the second investigating chamber. She will be joining a judge from Burkina Faso already in post.

In this context of underfunding, some think the court should establish a second trial chamber and open trials, rather than continuing to put money into investigations, since it may not be able to try more cases.

Here are the six cases considered ready or nearly ready for trial:

GUEN CASE

This is the most advanced case to date and is likely to be the subject of the fourth SCC trial. It should finally go to trial from around September, depending on the availability of the SCC’s sole trial chamber. On July 25, the trial section held a status conference behind closed doors in preparation for the trial.

This is a case of war crimes and crimes against humanity committed between February and March 2014 in the west of the Central African Republic, particularly in the towns of Gadzi, Guen and Djomo. The suspects are Mathurin Kombo, François Boybanda alias Balère, Philémon Kahena alias CB, Dieudonné Gomitoua, Jean Bahara (still wanted) and Edmond Beina. Beina alone is wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for the same crimes committed in Guen. But the SCC wants to add him to the case, which already includes five other defendants.

The charges relate to crimes against humanity and war crimes of murder, attempted murder, extermination, persecution, pillaging, forcible transfer of population, rape and sexual violence and other inhumane acts intentionally causing great suffering or serious injury to physical or mental health, including forced marriages. “After the resignation of President Djotodja in 2014, the Anti-Balaka [a predominantly Christian militia group] turned on the Muslim population in the streets of Guen and committed massacres against civilians, women and children,” says prosecutor Ouaby-Békaï. He puts the number of victims at 26.

BOSSEMBELE CASE

In this case, three people are waiting in jail for a fourth defendant who is unlikely to be arrested: former Central African President François Bozizé. These henchmen of his regime (2003-2013), Eugène Ngaïkosset, Vianney Semndiro and Junior Firmin Danboy, were arrested in 2021 and 2022 and detained at the SCC. The case mainly concerns crimes committed between February 2009 and March 2013 by the presidential guard and other internal security forces, in the civilian prison and at the military training centre in Bossembélé (north-west of Bangui).

Semndiro, an officer in the Central African Armed Forces (FACA), is charged with crimes against humanity for murder and enforced disappearance. He is alleged to have arbitrarily detained, executed and tortured prisoners while in charge of the town’s prison. Ngaïkosset, a former FACA and presidential guard captain nicknamed the “Butcher of Paoua” is also charged with crimes against humanity. He is alleged to have commanded a unit involved in numerous crimes, including the massacre of dozens of civilians and the burning of thousands of homes in the north-west and north-east of the country between 2005 and 2007. In addition, he is alleged to have committed crimes as a leader of the Anti-Balaka movement, notably in Bangui in 2015. Danboy is being prosecuted for crimes against humanity, including murder, enforced disappearance, illegal detention and torture.

As for Bozizé, the SCC has requested the cooperation of States through Interpol to obtain his arrest. An arrest warrant was issued on April 30. Tried in absentia last year, Bozizé, who created the Coalition des patriotes pour le changement rebellion in December 2020, was found guilty of undermining state security and murder. He has been resident in Guinea-Bissau since March 2023, in accordance with a roadmap for peace signed in 2021. “The State in which the former president resides expressed its opposition in a press statement to his extradition,” explains Ouaby-Békaï, “but we have gone through the usual procedure to refer the matter to the country that is harbouring him. We are awaiting their official reaction, also in writing. I believe that there is no judicial cooperation agreement with [this] country. We also know that this country has not ratified the Rome Statute [founding treaty of the ICC]. So it’s a matter of diplomatic negotiation. It could take a year, two years, three years. In the meantime, the prosecutor explains, a separation of the case could be requested, so that the accused who are present would be tried in person and Bozizé would be tried in absentia. "When the time comes, we will see,” he adds.

The prosecution order in this case dates back to September 2024, but it has been appealed. The court is hoping to get the case moving in September.

FATIMA 1 CASE

Long predicted to be the second case tried by the SCC, the Fatima 1 case has only gone backwards. The reason is that more and more arrests are being made in connection with it. The most recent is that of Mohamed Ali Fadoul, who was arrested on March 20, 2025. Eight other people have already been charged in connection with the case. They are Adamou Yalo alias Adamou Jésus, Hadiatou Gary, Abdel Kader Ali alias Américain, Youssouf Amat Youssouf, Amat Kalit alias Kaleb, Mahamat Abdoulaye alias Issa Mbongue, Ahamat Tidjani and Abakar Zakaria Hamid alias SG. One defendant in the case, Al Bachir Oumar, died in prison in 2023.

They are all charged with crimes against humanity for murder, extermination, persecution, enforced disappearance, cruel treatment such as torture, attacks against the civilian population, against places of worship, against property essential to the survival of the population, and pillaging.

The case concerns the first attack on the Catholic parish of Notre-Dame-de-Fatima, in Bangui’s 6th arrondissement. On May 28, 2014, elements of the Seleka rebel movement attacked the church, firing at point-blank range and throwing grenades into the building where thousands of people displaced by the armed conflict of 2013-2014 had taken refuge. Seventeen people lost their lives, including Abbé Emile Nzale. “We are on the point of closing the Fatima case,” says Ouaby-Békaï. “We are awaiting feedback from the examining magistrates in charge of the case so that we can file our final indictment. If they agree with us, we can consider bringing the case to trial, provided there is no appeal from the defence lawyers. If there is no procedural battle, we’ll be able to move very quickly.” He points out, however, that the defence teams “systematically” make use of their right to appeal.

The investigation could be completed between September and November, according to Justice Info sources.

FATIMA 2 CASE

Four years after the attack in May 2014, another attack targeted the same parish of Notre-Dame-de-Fatima on May 1, 2018. It all began with events involving a certain Moussa Empereur, who allegedly belonged to the self-defence group of Nimery Matar Djamous, alias Force (prosecuted but deceased). In the course of what happened, this man was allegedly wounded by the Internal Security Forces. In retaliation, a group of armed men from Km5, a predominantly Muslim district of Bangui, attacked the church of Fatima, where hundreds of Catholic worshippers had gathered for a mass in honour of Saint Joseph, patron saint of workers. The toll was high, with around a hundred people injured and 19 dead, including Abbé Albert Toungoumalé-Baba. Very few people have been arrested in this case, and the SCC has not released the identity of those it did have arrested. “For Fatima 2, there are still certain steps that need to be taken before we can consider closing the case,” says Ouaby-Békaï.

BANGASSOU CASE

As the civil war of 2013-2014 began to ease in Bangui and certain towns, a conflict broke out in 2017 between communities in Bangassou, the capital of the Mbomou prefecture in south-eastern Central African Republic. Self-defence groups attacked Muslim civilians. Dozens were killed in the fighting, forcing thousands of people to flee their homes. In July 2024, the SCC announced the arrest of three individuals, accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity in connection with this. They are Yvon Nzelété alias Kpokporo, Narcisse Christian Gomani Niakari alias Shogui, and Roger Linet. These three men are accused of having played a key role in the crimes, although the exact nature of the atrocities and the period in which they took place have not yet been revealed in detail due to the ongoing investigation.

The SCC has also indicated that the case against these three defendants will be joined to that of Abdoulaye Hissène, who was arrested a year earlier. “Abdoulaye Hissène, as a warlord, was everywhere at once. And we have a prosecution strategy to see where the best chance is of getting prosecution evidence. So we could have decided to prosecute him in the Ndélé 1 or Ndélé 2 case, but we decided to prosecute him in the Bangassou case,” explains Ouaby-Bekaï.

Some analysts see this decision as a way of avoiding confrontation between Abdoulaye Hissène and certain ministers still in office. Summoned to appear at the Ndélé 1 trial, Hissène did not wish to comment in detail and hoped that the court would also summon all those in the government allegedly involved in the inter-community conflicts in Ndélé. But Ouaby-Békaï says “it’s just a strategy on the part of the prosecution to get evidence [against Hissène]”.

The Bangassou case is still under investigation, and several other suspects and witnesses are still to be heard.

ALINDAO CASE

This is also a case that has been dormant before the SCC since Hassan Bouba “escaped” from Camp de Roux prison in November 2021 and returned to his government post as Minister of Livestock. The Alindao affair is very big considering the scale of an attack on a site for displaced persons that left 112 people dead in November 2018. The investigation could be closed at the end of July. Officially, only one defendant has been charged in this case: Idriss Ibrahim Khalil, alias Bin Laden, who became a soldier after the crime and was arrested in July 2022.