“This sentence doesn’t erase the suffering, but it is an act of recognition. It is the voice that tells Colombian society and the world that what happened was unjustifiable and inhumane. It not only marks the closing of a judicial chapter, but opens a new page for memory, justice and peace in our nation." This is how Justice Camilo Suárez prefaced the first of two guilty verdicts handed down last week by the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP), the special tribunal derived from Colombia's 2016 peace agreement.

On September 16, the judicial arm of the transitional justice model convicted seven former leaders of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) who were part of its leadership, for more than 20,000 kidnappings. Two days later, in a thoughtful symmetry, it did the same with 12 former military officials who took part in 135 extrajudicial executions, known to Colombians by the euphemism of 'false positives', in the Caribbean region.

These are landmark decisions for several reasons. The 19 convicted have admitted their responsibility for these crimes in moving public hearings and have apologized to their victims both publicly and privately. In that process Colombians saw Rodrigo Londoño or 'Timochenko', the last commander-in-chief of FARC, say "I felt disgust at our actions" and Colonel Héber Hernán Gómez Naranjo lamented "the cursed fruits of a dark alliance" with paramilitaries. Both former rebels and military were convicted of war crimes and crimes against humanity, the most internationally reproached legal qualifications.

This makes them the most tangible achievement so far for Colombia's innovative transitional formula, which privileges the satisfaction of victims' rights over prison sentences. While their announcement allayed many concerns that incubated during the long wait, they still leave crucial questions open, including under what conditions they will be held and whether that fulfils the restrictive component that sanctions should have. The long-term legitimacy of these decisions among Colombians and whether the Colombian model will continue to be a reference – and a possible route to close conflicts – in the world may hinge on the answer to these concerns.

"The enormous gravity of the crimes judged"

In its two rulings, the JEP’s highest section validated the findings that the teams led by justices Julieta Lemaitre and Oscar Parra laid down in their detailed 2021 indictments. It underscored that the FARC kidnapped thousands of people seeking economic ransom, pressuring a swap for imprisoned guerrillas and reaffirming their social and territorial control, while inflicting degrading treatment on them during captivity and causing enormous suffering to their families. It also reiterated that the military killed defenceless and vulnerable civilians – first local inhabitants and then persons from other cities tricked with false job offers – to falsely pass them off as rebels killed in combat in a bid to pad their achievements.

These convictions were the missing piece of Colombia's innovative transitional formula, which focuses on investigating, prosecuting and sanctioning those most responsible for the most serious and representative crimes. It does so through a two-track system and sanctions that combine two types of purposes: punishment and redress. Perpetrators who acknowledge their responsibility, provide truth and redress their victims can opt for a more lenient 5-to-8-year sanction of effective restriction of liberty in a non-prison setting, while those who choose not to do so face longer and prison sentences.

For the former FARC leadership, the JEP imposed this sanction’s higher threshold: 8 years during which they must work on projects to repair the damage they caused. It decided so by virtue of "the enormous gravity of the crimes judged and the high position of leadership, command and control that those sanctioned had in the armed organization, which increased their guilt and, consequently, their responsibility". The military received sentences ranging from five-and-a-half to eight years, given that some of them had already been in prison.

The inexplicable delay

The first result of the adversarial track should be known in October. After a year and fourteen hearings, another section of the same tribunal will decide whether Colonel Hernán Mejía, who was charged in the same Caribbean false positives sub-case but chose not to admit his role and go instead to an adversarial trial, is sentenced to up to 20 years in prison or is acquitted.

The historic rulings came seven years after the JEP opened its doors, a timeframe that is perhaps not long compared to the pace of the International Criminal Court (ICC) or UN tribunals such as those of Rwanda or the former Yugoslavia. But it is nonetheless difficult to understand for a tribunal that has already indicted 251 people and that, in the kidnapping and false positive cases, had filed its first indictments four and a half years ago.

In fact, the time between the moment these group indictments became final (what the JEP calls 'resolutions of conclusions') and the convictions was longer than the time it took the teams of the Acknowledgment Chamber to investigate and build the cases. A paradox given that the advantages of the Colombian model were, following the advice of former international prosecutor Louise Arbour, to encourage perpetrators owning up and unravel patterns of macro-criminality rather than choosing a case-by-case approach, in order to shorten the procedure and achieve judicial truths that touch more victims.

Projects to repair the damage caused

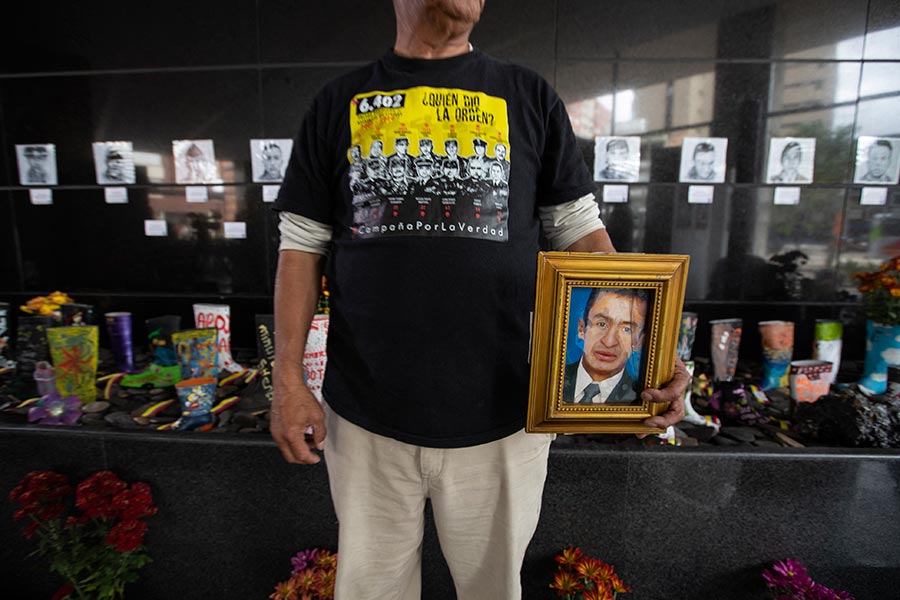

The JEP detailed, for the first time, how the restorative component of its sanctions will work. The seven former FARC leaders and the twelve convicted military officials, will "instead of remaining inactive behind bars, (...) work actively in the reconstruction of social fabric and the reparation of damages".

They will do so in projects consulted with victims and related to their crimes, which the tribunal calls "the heart of the special sanction”. Former FARC members will be required to search for people who are still missing, educate on landmine risk, work on environmental restoration and support memory initiatives, including installing tiles honouring kidnapping victims, similar to the golden cobblestones in German cities that commemorate those killed during the Holocaust. The military will do so in community infrastructure, memory programs and productive projects with its victims, including indigenous people of the Wiwa and Kankuamo peoples, and Afro-descendants of the Kusuto MaGende Community Council. In the JEP’s words, the idea is to "work directly and sustainably on victims’ redress", instead of "suffering a passive custodial sentence".

In both cases, the JEP allowed a discount in the time of the sanction. The former rebels were allowed to deduct from their reparations obligations the time they spent in similar restorative actions prior to their conviction. Applying a formula of one day deducted for every two days in these initiatives, the JEP authorized most of them to deduct seven months and one of them, Jaime Parra the 'Doctor', eleven. Some military personnel received shorter restorative sanctions because they have been detained in the ordinary justice system.

For all those sanctioned, these benefits are conditional on them participating in restorative projects, continuing to provide truth and not committing further crimes – what the peace agreement calls the 'conditionality regime'. Its sanctions, says the JEP, seek "not to benefit perpetrators with reduced sentences, but to optimize the rights of victims in a transitional context different from that of classic retributive justice".

Although the JEP has complained about the difficulties in financing these projects and coordinating with the government to implement them, more so during a year Colombia lost millions of dollars in international aid, it decided to create them from scratch instead of appealing to collective reparation measures resulting from the peace deal or the 2011 Victims’ Bill that are already in place. These include victim’s return and collective reparation plans, as well as the Development Programs with a Territorial Approach (PDET) that were designed with 300,000 victims and inhabitants of the municipalities historically hardest hit by war.

"There are scores of reasons for this to be the option: they are in the regions where the conflict had the greatest impact, they are already the result of having asked the communities and victims, and they were the fruit of a huge state investment in time and resources. All three have already proven routes," says Emilio Archila, a former peace deal implementation advisor who led its planning for four years.

How far can convicts move around?

Where the greatest doubts lie is in the retributive component of the sanction, which the peace deal called 'effective restriction of liberty'. It is an ambiguous term that sought to differentiate it from ordinary prison while fulfilling the Colombian state's obligation, under international and national law, to apply effective sanctions for atrocious crimes.

The two sentences stipulate that the convicts will see a "restriction of their rights and freedoms". They will be monitored by a three-pronged committee: the JEP’s executive secretariat will do the day-to-day work, the tribunal section that handed down the sentences will do judicial follow-up, and the UN special mission in Colombia will be the guarantor. This monitoring will be done through in site visits and with a "non-invasive (PDA type) electronic device", with geo-referencing and geo-fencing functions to alert if they leave a certain perimeter. In the words of chairman Alejandro Ramelli, "this is not a formality: these are sanctions monitored by the JEP and the international community, as well as by the communities where these sentences are carried out".

Although the rulings repeatedly state that they comply with international standards, this scheme leaves important concerns. The sentence against the FARC speaks of an "authorized perimeter," but at no point does it detail what it will be. This contradicts the peace agreement and the JEP procedural law, which ordered it to "concretely establish the territorial spaces where those sanctioned will be located during the time periods of execution and compliance with the sanctions of the transitional justice system, which will have a maximum size equivalent to that of the Transitory Zones of Normalization" in which they laid down their weapons. The size of those areas was between 5 and 15 hectares.

On the other hand, the ruling against the military provides more details about this restriction, mentioning the extension of the disarmament zones and explaining that "they will be located in the municipality closest to the place where the restorative project will take place" and that "they won’t be able to change their city or municipality of residence without this Jurisdiction’s knowledge and prior authorization". In case they do not have a residence, they may abide by the same conditions in a military unit.

The lack of clarity on restriction, especially of the ex-FARC, means that there is a risk that the JEP might not comply with its obligation that the "sentences imposed (...) will precisely state the content of the sanction, place of execution of the sanction, as well as the conditions and effects of the sanctions for crimes not liable for an amnesty". It is also unclear whether this difference complies with the procedural law’s determination that the criminal treatment for FARC and State agents must be "equitable, balanced and simultaneous".

In addition, none of the rulings makes it clear whether the surveillance devices are bracelets worn on the body or beepers that they carry, only that "they must be used permanently until the end of their sanction". The JEP’s executive secretariat assuming the brunt of the monitoring work, it is also not clear what will happen when the tribunal’s closure date comes in 2034 (especially with all the pending sentences).

Participation in politics allowed

One right that the JEP decided not to limit is that of political participation, a debate that has accompanied it since former guerrillas began to reach elected office. In the end, it decided that sanctions are compatible with the exercise of public functions, with two rules: political activity cannot be used to voice "negationism or revictimising speeches" and, in case of a tension between both, the sanction will take precedence. However, in the absence of a clear perimeter, it’s not possible to establish where political activities that are compatible with the sanction may take place. Given that the tribunal weighed political participation against the special sanctions in general and not against the particular sanctions it handed down in this case, how an incompatibility will be defined is still up in the air, as well as whether these are related to physical places or work schedules for restorative projects.

In the short term, this decision benefits ex-FARC Julián Gallo and Pablo Catatumbo Torres, now senators for the Comunes party by virtue of the political participation provisions of the peace agreement that gave them ten seats in Congress for two legislative periods (which end next July), as well as two other former guerrilla leaders, Pedro Baracutao and Jairo Cala, who are also legislators and are charged in other cases. In the long term, it allows them all to run for elected office in the 2026 elections.

The legacy of the Colombian model

How this effective restriction of freedom ends up looking for the 19 convicted may well be decisive on how the sanctions imposed on the former FARC and military are received in the long term by victims and Colombian society.

It faces a daunting task. Two surveys, conducted by political scientists Sandra Botero and Juan Carlos Rodríguez Raga five years apart, asked more than 1,500 Colombians about a hypothetical person guilty of homicide who received house arrest and worked in humanitarian demining. In both scenarios, a greater number of respondents valued a punitive approach of a prison sentence more highly than a lighter but redress-oriented sanction.

Outside the country there have been warnings too. Karim Khan, the (now suspended) ICC prosecutor, stated in the 'cooperation agreement' with which he closed his preliminary investigation into Colombia in 2021 that he could reverse his decision if there were "any significant change in circumstances". Among the scenarios it warned about is "the enforcement of effective and proportionate penal sanctions of a retributive and restorative nature".

To add another complexity, with eight months to go before the next presidential elections, transitional justice sanctions could once again become a wedge issue. Former President Álvaro Uribe, recently convicted in the first instance for bribing witnesses, reactivated his attacks against the JEP, accusing it of forcing military to "admit crimes not committed" and proposing for them a review in the ordinary justice system with sentences of up to five years.

It may depend on the answers given by the special tribunal to these questions that, as justice Ana Manuela Ochoa – a Kankuama like many false positives victims – said before symbolically storing the second ruling in an indigenous rucksack, "the transitional and prospective justice implemented by the JEP not only serves to respond to the past, but also as a starting point to promote reforms and guarantee non-recurrence of violence".

The 7 FARC leaders sentenced to 8 years

- Rodrigo Londoño, alias Timochenko

- Pablo Catatumbo Torres

- Pastor Alape Lascarro

- Milton de Jesús Toncel, alias Joaquín Gómez

- Rodrigo Granda

- Jaime Alberti Parra, alias Medico or Mauricio Jaramillo

- Julián Gallo, alias Carlos A Lozada

The 12 members of the national army sentenced

- Guillermo Gutiérrez Riveros, major (8 years)

- Heber Hernán Gómez Naranjo, colonel (6 years 5 months)

- Efraín Andrade Perea, sergeant (6 years 1 month)

- Manuel Valentín Padilla Espitia, sergeant (8 years)

- Carlos Andrés Lora Cabrales, lieutenant (5 years 10 months)

- Eduart Gustavo Álvarez Mejía, second lieutenant (8 years)

- José de Jesús Rueda Quintero, sergeant (6 years 11 mnths)

- Elkin Leonardo Burgos Suárez, second lieutenant (5 years 7 months)

- Elkin Rojas, corporal (6 years 1 month)

- Juan Carlos Soto Sepúlveda, soldier(6 years 7 months)

- Yeris Andrés Gómez Coronel, soldier (7 years 7 months)

- Alex José Mercado Sierra, soldier (6 years)