Sciences Po Paris

المقال متوفر باللغة العربية / This article is also available in Arabic on the Syrian Justice and Accountability Centre (SJAC) website.

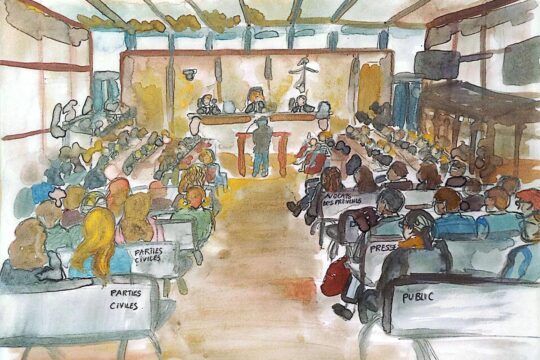

The third week of the Lafarge trial, which started November 24 before the 16th Chamber of the Paris Criminal Court, was devoted in particular to examining the evidence for the offence of terrorism financing.

The focus was first on understanding which groups were involved and whether the former Lafarge executives were aware that these were terrorist organizations. To shed light on this, hearings began on Monday with the testimony of an agent from the DGSI, France’s General Directorate for Internal Security, an agency responsible for combating terrorism. The man was heard via videoconference, with his identity supposedly masked. At 3 p.m., however, just as the connection was restored after a network interruption, an incident occurred: for about 15 seconds, the French intelligence agent appeared on the screen before his image was blurred out.

For more than three hours, the DGSI agent gave the court a geopolitics lesson on the situation in Syria from 2012 to 2015. He identified the forces present around the Jalabiya cement plant, notably the three jihadist groups to which Lafarge is accused of transferring funds: JAN (Jabhat Al Nosra), ISIL (Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant), and Ahrar al-Sham. He stressed that the atrocities committed by JAN and ISIL were widely reported in French media, making them publicly known and leaving little doubt, in his view, that they were recognised as terrorist organizations.

Very quickly, the question resurfaced as to whether French intelligence services had any knowledge or involvement in the case. Solange Doumic, lawyer for former Lafarge deputy CEO of Operations and Supervisor for Syria Christian Herrault, pointed out that former Lafarge head of security Jean-Claude Veillard had lunch with intelligence agents on several occasions, particularly during the summer of 2014. The witness evaded this question, as with others, citing compartmentalization within the services. He suggested asking Veillard if he remembers these lunches. Herrault’s lawyer then replied: “Mr. Veillard was fortunate enough to have his case dismissed; he will come [to court on December 9 as a witness] to give probably the same testimony as you.”

Former Lafarge executives claim to have been victims of the “Veillard system”: “I experienced the situation through Jean-Claude Veillard’s security committee,” explained Herrault. Veillard remains the ghost of this trial, and his potential role as an informant for the intelligence services remains unclear. This opacity is compounded by the fact that emails exchanged with the DGSI between 2013 and 2014 have not been declassified: curiously, only correspondence before and after the period examined by the court has been made available.

Throughout the week, however, the presiding judge conducted a thorough review of emails exchanged between the company’s executives at the time. Projected on screen and analysed word by word, these emails evidently became increasingly explicit over the months, making it difficult for executives to maintain the narrative of having been victims of racketeering and unaware of the situation.

Tlass paid via an offshore account

On Thursday, the court focused on analysing financial flows and the mechanisms that made these money transfers to armed groups possible [see a presentation of the organisational structure of the defendants at the link]. An email sent to Christian Herrault in 2013 illustrates the intention of Bruno Pescheux, former director of the Syrian subsidiary, Lafarge Cement Syria (LCS), to conceal any trace of association between LCS and Firas Tlass. Lafarge made payments to Tlass via an offshore account. Tlass, a minority shareholder in the Syrian subsidiary, was the central figure in this transaction system. Subject to an international arrest warrant, he is absent from the present trial. The defendants argue that, thanks to his network of contacts, Tlass had become an indispensable intermediary in keeping the factory operational.

“We were completely duped by Tlass; he led us on until the very end,” said another former LCS director, Frédéric Jolibois. Former Lafarge executives say they lost all control over Tlass and his activities. They reject their own responsibility. “I had to orchestrate, so I’m an arranger or a facilitator, but not a composer,” said Pescheux. When the presiding judge asked why Tlass had been kept in this role as an intermediary with armed groups, he replied: “We thought the tunnel was much shorter than it turned out to be,” indicating that he had not fully grasped the scale of the conflict and its consequences.

The National Anti-Terrorism Prosecutor’s Office (PNAT) pointed out that at the height of the Syrian crisis, demand for cement was growing. Indeed, the war had made it “easier” and faster for the Syrian government to issue building permits, increasing the number of projects carried out.

Unequal treatment of employees

At the end of June 2012, the security committee noted that the situation around the factory was not improving. During this period Pescheux, director of LCS (from 2008 to July 2014), left Damascus for Cairo, from where he began managing the factory remotely, and proceeded to evacuate expatriate executives. He maintains, however, that he had always believed the situation would eventually improve.

When asked about the decision to restart production in October 2012 after a month-long shutdown, Pescheux stated that all employees had received equal attention in terms of their safety. He said that in a context marked by increased kidnappings of foreigners in Syria, management was primarily concerned about the risks facing expatriates housed 160 kilometres from the factory. It is noteworthy that Syrian employees were not evacuated, despite being exposed to the risk of kidnapping and violence during their commutes.

What, then, was the basis for the decision to resume operations? Pescheux insisted that in 2012, staff safety was “guaranteed” thanks to the payments made by Tlass and the checkpoints employees had to pass through to get to the factory. The level of security had returned to “acceptable” levels, and pressure from the employees themselves had encouraged the resumption of production. Pescheux said he hoped that this system of passing through checkpoints would allow them to continue their activities. Everyone was aware of this arrangement, but, he added, “We all assumed it wasn’t going to last.”

Drivers executed at a checkpoint

The defendants tried to convince the judges that the Syrian workers themselves asked to return to work at the factory. On November 27, however, a witness for the civil parties, A.H, testified to the contrary. This former Syrian employee of Lafarge is one of eleven who initially filed a complaint against the company in 2016. Currently living in Germany, he gave his testimony via videoconference, with simultaneous translation. When he joined Lafarge, H. says he believed that he was joining a Western organization that embodied respect for human rights. He told the court of his disappointment. When asked about his rights and compensation, the witness explained that even if he stopped working due to dangerous road conditions, “you were not entitled to compensation, you were [considered] absent”. A lawyer asked him if he had contacted a factory manager. He explained that he had never spoken to Jacob Waerness, LCS’s safety manager at the time. He said he had not known Waerness was responsible for employee protection, revealing a clear disconnect with the employees.

Contrary to what one might think, the war did not slow down production at the cement plant. H. explained that during the most critical periods of the conflict—particularly in 2014—the plant’s production peaked. Lawyers for the civil parties questioned him in turn about the kidnapping of one of his friends, the departure of his colleagues, the fear surrounding daily travel, and the absence of any guarantees for his safety.

The courtroom fell silent when he mentioned a horrific incident at a checkpoint involving Lafarge drivers. Employees had to pass through around three checkpoints to get to the factory in 2012. The PNAT referred to a video submitted as evidence, showing how these drivers were arrested, subjected to a brutal interrogation – including on their knowledge of prayers - and then executed a few minutes later.

The absence of a genuine evacuation plan and safety measures for Syrian workers was becoming increasingly apparent, with more and more contradictions and inconsistencies. On the stand, Herrault claimed he intended to “reopen the factory in order to close it down and empty the silos”, a plan he claimed to have discussed with Jolibois. Yet Jolibois contradicted him in court, saying, “I was not aware of this information”. Once again, the versions of events recounted by Lafarge’s former executives appear to collide.

A theatrical trial

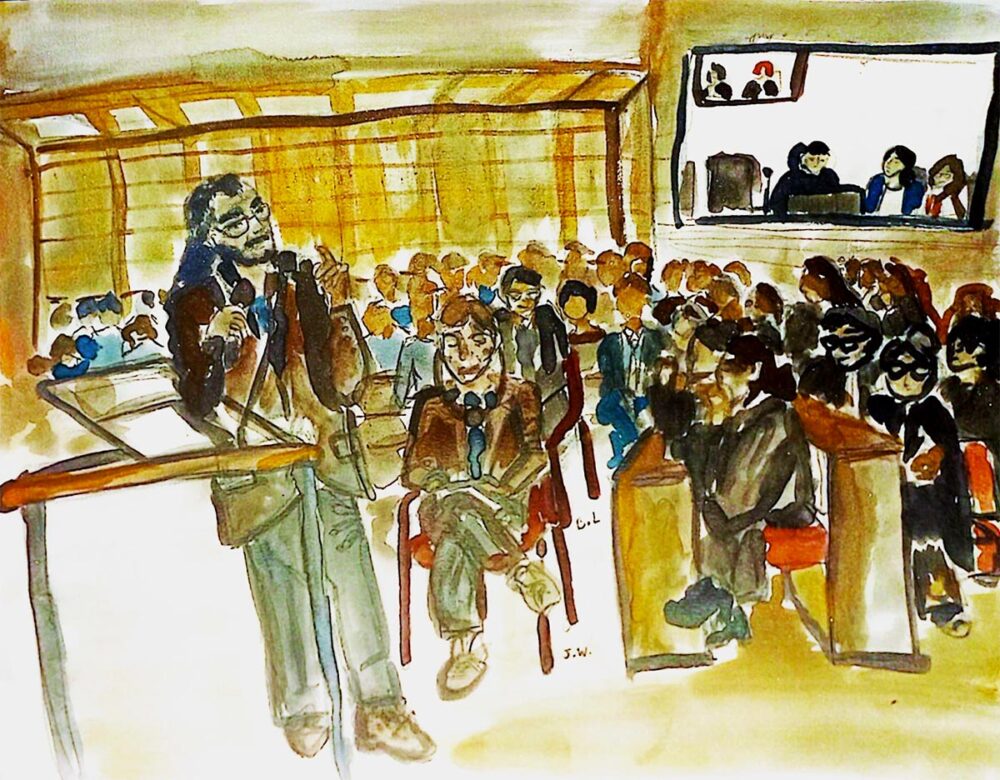

At times, the hearing resembles a stage performance, with the audience watching the constant coming and going of defendants to the stand, sometimes three at a time, or accompanied by their interpreters. In a matter of seconds, narratives overlap, and contradictions emerged. Presiding judge Isabelle Prévost-Desprez seemed determined to extract the truth through a dramaturgical pace, before a courtroom that remains consistently full. Dominating the courtroom from her podium, she provoked laughter when she ironically pointed out inconsistencies in the defendants’ accounts, unsettling these former business leaders who are nevertheless used to ruthless business battles. Facing her, they remained courteous and tried to provide answers. At the end of the afternoon, the presiding judge ordered a recess: a pause during which defendants, lawyers, families, journalists and civil parties mingled in front of the courtroom or in the cafeteria, chatting over coffee. In this trial, hearings sometimes last until 10 p.m. As in an overly long play, attention wanes, people in the audience leave, and some defendants yawn. Many are elderly, some are ill, and sitting through more than eight hours in court is an ordeal.

As part of the Capstone Course in International Law in Action, Professor Sharon Weill and eleven students at Sciences Po Paris, in partnership with Justice Info, are dedicated to weekly coverage of the Lafarge trial, conducting an ethnography of the proceedings. The members of this student group are Sofia Ackerman, Maria Araos Florez, Toscane Barraqué-Ciucci, Laïa Berthomieu, Emilia Ferrigno, Dominika Kapalova, Garret Lyne, Lou-Anne Magnin, Ines Peignien, Laura Alves Das Neves, and Lydia Jebakumar.