On December 3, it was only 13 days to the 21-year anniversary of the killing of Deyda Hydara, a veteran Gambian journalist who co–founded The Point, one of the country's leading daily newspapers. Hydara was killed in a drive-by shooting by members of a hit team, called the Junglers, allegedly on the orders of the then president Yahya Jammeh who now lives in exile in Equatorial Guinea.

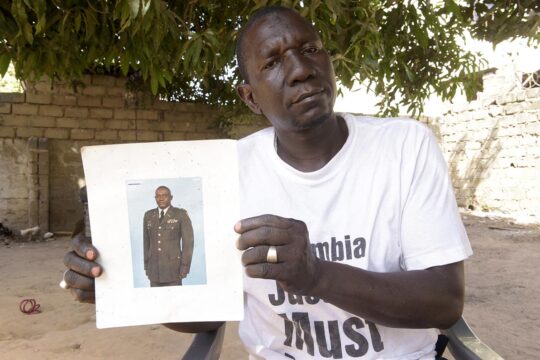

As Hydara’s family prepared to remember him, a rather unusual present came by. Former Lieutenant-Colonel Sanna Manjang, described by The Gambia’s Truth, Reconciliation and Reparation Commission (TRRC) as one of the two “most feared” Junglers, was arrested in the jungles of Casamance, Senegal’s troubled south. He was then extradited to The Gambia where he was welcomed with a three-count murder charge, including the death of Hydara. And on December 3, the journalist’s son, Baba Hydara was at the Kanifing Magistrate Court, in Gambia’s capital city, to see Manjang one on one for the first time.

“I got prior knowledge that he was coming to the court. I went to stand in front of him. I stood in his path to the courtroom and I stared at him. He was covering his face,” Hydara told Justice Info. “I wanted to push his hands for him to look at me. I am sure he must have seen my face somewhere. It is a promise I made that I have to make sure that all the people connected to my father’s death, I will somehow have a role to play in bringing them to justice and have a day in their court.”

“One step closer to the dictator”

Manjang was arrested in a joint operation of Gambian and Senegalese security forces. While many had heard of his name, only a few knew his real face, save for an old picture of him and colleagues taken in the 2000s. In the immediate aftermath of his arrest, even online newspapers were sharing wrong pictures of other nationals who were found where he was arrested, claiming it to be Manjang. Until December 1, when a video emerged showing Manjang with a smirk, as Senegalese authorities checked the tightness of his handcuff before handing him over to Gambia’s military police.

Before the court, Manjang was charged with the 2004 killing of Hydara as well as the 2006 killings of one Ndongo Mboob and a cousin of Jammeh, Haruna Jammeh. The police had already called a number of relatives of his alleged victims to appear before their investigation panel. Meanwhile, his murder trial has been moved to the High Court in Banjul to be presided over by Justice Sidi K. Jobarteh. Trial hearings were set to begin on December 11, while the case is put together. Evidence gathered by the TRRC is likely to be central, including testimonies from other Junglers, who may be called as prosecution witnesses.

Many experts believe that Manjang is a black box that holds the secret of most of Junglers’ operations and killings. Leading Gambian human rights activist, Madi Jobarteh, said his arrest opens doors for the eventual trial of Jammeh. “With his arrest, we will have information about the network of Junglers outside. It is one step closer to the dictator himself,” he said. “It is a very significant development.”

A tense political moment

Adama Barrow, who has been the president of Gambia since the fall of Jammeh in January 2017, has not shown much interest in justice since the end of the TRRC in 2021. But he does care about the security of his regime. When Manjang was arrested, the rumour doing the rounds was that the former Jungler was involved in a coup attempt. This is because of the timing of the operation: shortly before Manjang’s arrest, Gambia was under a heightened security alert, as exiled leader Jammeh had announced he was returning to Banjul in November without mentioning the exact date.

“Jammeh is emboldened because he senses that the government, and in particular the president has shown a certain weakness, a certain inclination to compromise as far as such compromise will yield political dividends in the form of support for him and his party,” said Dr Baba Galleh Jallow, the former executive director of the truth commission. According to him, Jammeh would have been much less relevant in Gambian politics if the government were “serious, more focused, and had shown more political will” in implementing recommendations by the TRRC. A report by the National Human Rights Commission published this year said the government so far implemented only 16 out of 192 recommendations made by the Commission.

Jammeh’s announcement was received with cheers by his supporters who started hoisting flags on the streets in Banjul. The Barrow administration is still guarded by Senegalese troops that are part of the ECOMIG contingent, a West African force. With deep-seated suspicion of Jammeh’s motives and his potential allies in the military, the government was not enthusiastic about the prospect of the former dictator’s return. “If and when Mr. Jammeh returns, robust legal processes will be activated… including investigation, arrest, and prosecution,” said the government in a statement on October 28, dispelling claims that it had signed an agreement with the seven-party 2016 coalition that backed Barrow to power, the United Nations and the African Union that would guarantee Jammeh’s return and freedom.

Shortly after Jammeh announced his return, Barrow started an annual nationwide tour, holding meetings in several villages and towns across the country. He took advantage of these meetings to criticise Jammeh’s poor human rights records, saying he had exiled many of his critics, and even prevented bodies of few of them who died abroad to be repatriated to the country for burial.

Since 2021, after accepting the recommendations of the TRRC, the Gambian authorities have been working on establishing a special, internationalised tribunal with the help of the regional economic bloc Ecowas to try Jammeh-era crimes. But the process has never been brought to fruition. It is unclear when the court would be established, even though a special prosecutor to handle Jammeh-era crimes is expected to be appointed in January.