On May 18, 2022, the Paris appeals court confirmed a charge of “complicity in crimes against humanity” against French cement group Lafarge. The multinational is suspected of having financed terrorist groups including Islamic State via its Lafarge Cement Syria subsidiary, and of having participated indirectly in crimes committed in Syria between 2013 and 2014. "This is the first time anywhere in the world that a parent company has been indicted for activities of a subsidiary abroad, and that a company has been indicted on such serious charges: terrorist financing, complicity in crimes against humanity and deliberately endangering the lives of others," says Marie-Laure Guislain, main architect of the initial complaint against Lafarge by the NGO Sherpa. "This last charge is extremely important because it can now be used against other companies if their activity negligently or deliberately endangers the lives of employees."

A few weeks later, on June 2, 2022, three human rights NGOs filed a complaint with a Paris court against French arms companies (Dassault Aviation, Thales Group and MBDA France) for their "possible complicity in alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity in Yemen, which may have been committed as a result of their arms exports to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates”.

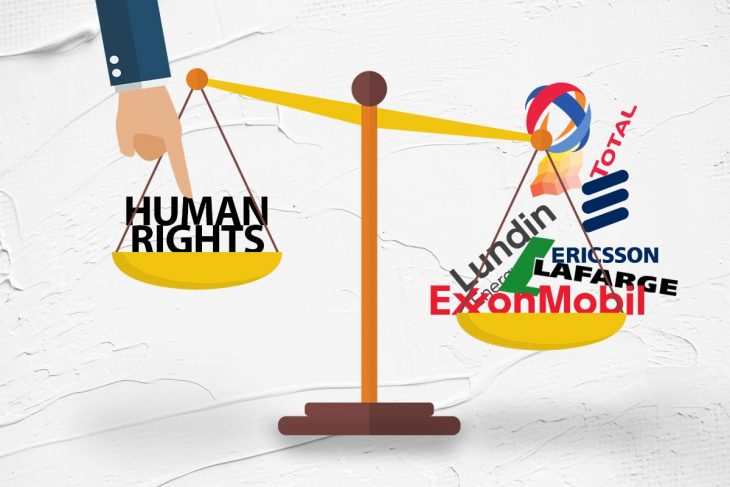

With the recent prosecutions of Swedish multinationals Lundin Energy in connection with war crimes in Sudan and Ericsson in connection with war crimes in Iraq, the movement to hold multinationals accountable for certain international crimes is growing.

Individual responsibility first

So far, only one example has truly marked the history of international criminal justice in the effort to hold business accountable. Between December 1946 and October 1948, trials were held of the German industrial groups Krupp, IG Farben and Flick, in the context of prosecutions organized by the Americans after the Inter-Allied Military Tribunal in Nuremberg. Alfried Krupp, the son, was sentenced to 12 years in prison, along with eleven other company executives; fourteen executives of chemical giant IG Farben were given light sentences and the boss, Friedrich Karl Flick, was sentenced to seven years in jail. But no company was convicted as an entity.

The desire to hold corporations accountable for certain international crimes is not new, but they remain largely unpunished for human rights violations committed around the world because of their status which gives them almost total protection. "In all of criminal history for centuries, it has been the individual that counts. The company is not, a priori, responsible for the crime, even though it is a social actor that has an absolutely decisive role," explains Sylvain Savolainen, lawyer and member of the human rights commission of the Geneva Bar Association. Thus the responsibility of companies has been excluded from international criminal jurisdictions, which only recognize individual responsibility. No international lawsuit can be brought against them; only their employees can be prosecuted.

With various declarations and guidelines (see timeline), efforts have been made at international level to gradually oblige companies to respect human rights. So far, however, such efforts have not gone beyond non-binding principles.

International justice powerless

In 1984, the Bhopal tragedy in India shocked the world. Twenty thousand people died of poisoning in the explosion of an agrochemical plant belonging to the American multinational Union Carbide. "Faced with these violent and brutal deaths, similar to those of Chernobyl [two years later], there is an international awareness that a company can do damage," says Savolainen. "Between the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st, a whole series of events made it clear that companies played a role in conflicts in places like Sierra Leone, Liberia, Rwanda and South Africa during apartheid – even if the finger was not pointed at them directly."

It is in this context and especially following the work of American law professor John Ruggie, special representative of the United Nations Secretary General, that the "UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights" were adopted in June 2011. Adopted unanimously by the Human Rights Council, these 31 so-called "Ruggie principles" formalize the concept of "due diligence" and its application to companies: they must take proportionate measures to identify, prevent and remedy the negative impacts of their actions on human rights. This is still so-called "soft law" since non-binding, but Savolainen says it "is causing a tsunami that places corporate responsibility for human rights at the heart of companies' concerns".

However, the criminal impunity of companies remains massive in the face of the powerlessness of international jurisdictions to try them. As far as national jurisdictions are concerned, a few countries can now prosecute companies in criminal or civil cases; this is notably the case in France which, in the Lafarge case, has for the first time recognized its universal jurisdiction to try a company and its managers for international crimes committed outside the country. "It is a huge new avenue that has been opened by France -- an example so strong that all companies in the world will be careful not to make the same mistake," Guislain hopes.

Failure of Texaco-Chevron case

The Texaco-Chevron case is an emblematic example of the difficulty of initiating proceedings against multinationals accused of serious human rights violations. Between 1967 and 1993, the American oil company dug 350 oil wells and 880 retention basins in the Amazonian forest. Thirty thousand people were poisoned by the toxic wastewater discharged into the rivers. In 1993, victims sued Texaco-Chevron in the United States, where the company was headquartered. The case was finally referred to the Court of Justice of the Ecuadorian region of Sucumbio, which, in February 2013, ordered the multinational to pay 9.5 billion dollars in reparations. But on August 30, 2018, the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague overturned this conviction, finding that "Ecuador is responsible for denial of justice". At the same time, Texaco-Chevron took the case to a private international court of arbitration and got Ecuador ordered to pay compensation for the inconvenience caused by the lawsuit.

Twenty-six years later, the victims are still waiting for compensation. "This shows us one thing: how multinationals get away with it," remarks Valérie Cabanes, a French lawyer who campaigns for the recognition of ecocide before the International Criminal Court (ICC). "On average, more than 60% of cases brought against multinationals end up in their favour. What I have been denouncing for years is this form of supremacy of commercial law which has been established above human rights, environmental law and, a fortiori, the rights of nature if they were recognized."

The Texaco-Chevron case pushed Ecuador, along with South Africa, to initiate in June 2014 an intergovernmental working group open to civil society. Mandated by the United Nations, it was tasked with developing an international treaty binding multinationals to respect human rights. "This has created a fascinating political space: a real battle over whether companies should be held directly accountable for human rights under international law or not," comments Australian lawyer Joanna Kyriakakis, author of a recent book entitled "Business, Accountability and International Criminal Law”. "The draft does not propose to impose direct human rights obligations on companies," she explains. "It seeks ways to encourage states to meet their human rights obligations by ensuring that companies are adequately regulated and held accountable for human rights abuses.” If successful, "this binding multilateral treaty would be a historic opportunity to change international law, prevent human rights abuses by corporations and reduce the current power imbalance between people, the planet and corporations," according to the National Centre for Development Cooperation, which coordinates Belgian NGOs working in international solidarity. After three revisions of the text, however, the negotiation process still faces many obstacles.

International Criminal Court: a false hope?

"By putting responsibility only on individuals, the founders of the ICC must have thought that one day they would add collective corporate responsibility. But we're still waiting," says Mark Drumbl, a professor at Washington and Lee University in the United States. Indeed, says Cabanes, "the Rome Statute [which gave birth to the ICC and came into force in 2002] only concerns political or war leaders. It was never intended to include multinationals and their leaders as subjects of international criminal law. This is a real pitfall in the law". Experts in international law have been debating for decades the capacity of the ICC to effectively tackle multinationals that commit international crimes, but there has been no real progress. For Drumbl, the reason is structural: "The ICC evolves in a liberal market democracy, incompatible with the recognition of corporate responsibility."

Guénaël Mettraux thinks it is not just lack of will but especially the ICC’s lack of resources, which restrict the court in terms of what it can promise. "If you promise victims that you can compensate them or give reparations for their harm, you have to have the legal and financial means to do so. And the ICC doesn't have them," says this international crimes specialist and judge in the Kosovo Specialized Chambers who has acted as a consultant for Lundin Energy, a Swedish company whose executives are being prosecuted in Sweden for allegedly aiding and abetting war crimes in Sudan. "Economic actors must be held accountable for their activities, but at the same time, the ability of international criminal law to deal with such issues should not be exaggerated," Mettraux adds. Valérie Cabanes is also forgiving of the international court. "It is a decision by States not to give it the means to act. So, indeed, it disappoints because it does not conduct as many investigations as it could, it doesn’t have enough convictions because the investigations take long and require a lot of means. But there is a real willingness on the part of the ICC to seek solutions to adapt to the times.”

The lawyer is referring to a directive from former ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda, who in 2016 appeared to open a path by announcing, among other things, that environmental violations that could constitute crimes against humanity were among her new prosecutorial priorities. Nothing came of it. However, international humanitarian law academic Jelena Aparac believes that the ICC is the preferred jurisdiction. "Bringing international corporate accountability to the ICC may be a way for it to counter criticism, breathe new life into it, and give it more legitimacy by creating the possibility for it to correct the narrative on ongoing conflicts and the role that some multinationals play," she writes.

It is nevertheless at national level that the most concrete action has been taken, as shown by the Lafarge, Lundin and Ericsson cases.

“Due diligence”

In response to the Rana Plaza tragedy - the collapse of textile workshops in Bangladesh on April 24, 2013, which killed 1,138 workers supplying major Western brands – France on March 27, 2017 passed a "Law on the due diligence parent companies and companies giving orders”. It provides for "the engagement of their responsibility in case of failure to comply with these new obligations aimed at preventing the risks of serious human rights and environmental abuses, including when committed by their direct or indirect subsidiaries in France and in the rest of the world".

A first evaluation report, published on February 21, 2020 by the Conseil général de l'économie, presents a mixed assessment and reveals that "while some companies have made real progress in taking into account the issues raised by the law, others are applying it in an unsatisfactory manner that does not allow the due diligence to be effective". Of the three formal notices issued for inadequate due diligence plans, two concern the oil company Total for, in particular, "failure to mention the impact on local populations of a specific project in Uganda". Total's "Tilenga" project plans to exploit oil under Lake Albert, on the western border of Uganda, in parallel with the "Eacop" project in Tanzania, which plans to transport this oil via a pipeline linking the two countries. Denouncing the human and environmental impact of "Tilenga", NGOs Friends of the Earth France, Survie and four Ugandan associations took the oil giant to court in Nanterre in 2019. On December 15, 2021, the Court of Cassation confirmed the jurisdiction of this court. Another hearing, scheduled for late 2022, will be the first legal action based on due diligence.

Pressure in Europe

Norway and Germany have passed similar legislation. The Netherlands, Spain and Belgium are considering it. Switzerland narrowly rejected strong legislation on corporate responsibility on November 29, 2020 in a "popular initiative for responsible multinationals". New obligations in terms of human rights and the environment would have been created, such as the production of an annual report by Swiss companies and their liability before Swiss courts for their subsidiaries and subcontractors who may be at fault. "I think the ‘no’ side considered it unfair to subject companies to standards that would make them uncompetitive internationally," says Mettraux. "If this had been done in the framework of an international or regional convention at European level, it would have passed easily.”

On February 23, 2022, following a decision by the European Parliament in favour of legislation on corporate responsibility for human rights and the environment, the European Commission adopted a proposal for a directive on corporate due diligence on sustainability. Acknowledging an "essential and long-awaited step towards recognizing corporate responsibility for human rights and ensuring access to justice for victims", NGOs nevertheless call for "remedying some significant shortcomings" in this legislation, such as the burden of proof "which still rests with the victims, who must prove that the company has failed to meet its obligations". The NGOs also regret that "the possibility provided by French law to refer a case to a judge before harm is done and get an order for the company to respect its obligations is not explicitly envisaged in the [European] Commission's proposal".

The Latin American model

In Latin America, it is the transitional justice processes following conflicts or dictatorial regimes that have made this region one of the most competent in the world for dealing with victims of serious corporate violations. "This is the result of enormous efforts by groups of victims, survivors and human rights defenders in civil society, combined with the existence of a strong regional human rights body in the Inter-American Commission and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights," explains Leigh Payne, professor of sociology at the Centre on Latin America at Oxford University.

The Inter-American Court has ordered its member states to integrate international human rights conventions into their legislation. "Almost all Latin American countries have incorporated international human rights law into their domestic law in the form of constitutions, but also in criminal law codes. This means that victims do not have to depend on international courts, but can rely on local courts to apply the law," says the American specialist. She gives the example of the Volkswagen company in Brazil, which was ordered to pay collective reparations to families whose members -- trade unionists and Communist activists who worked at the company -- were arrested and tortured under the Brazilian military regime (1965-1984). In 2014, in its final report on the investigation of the crimes of the dictatorship in Brazil, the Brazilian National Truth Commission established that some 50 companies had collaborated with the military regime.

More awareness within multinationals

Stéphane Brabant, 65, has a long career as an international lawyer advising companies on human rights issues. "Twenty years ago, human rights issues were completely unknown in the business world," he recalls. Consulting firms like Trinity International, where Brabant was hired in 2021, have since proliferated. "My job is to ask company managers if they have thought about taking all the necessary measures on the environmental and human rights front, in consultation with local populations," he explains, welcoming the French law on due diligence. "Companies are now taking a huge risk - reputational and trust – if they don’t do this."

Valerie Cabanes also admits she sees the beginning of a change. Invited on April 10, 2019, to present the concept of ecocide before several hundred entrepreneurs gathered at the Palais des Congrès in Paris, she says she received a standing ovation from the business leaders. "I really didn't understand. They told me afterwards that they were completely on their own, often aware that they were doing things that were dangerous in the long term, but that, without a binding legal framework, they remained tied to this objective of profit and to their shareholders. I felt there was a new awareness on this subject."

The legal director of an international group with 35,000 employees, who wishes to remain anonymous, recognizes the "moral success" of this law on due diligence and hopes that "France will provoke a virtuous contamination in Europe". However, he regrets its imprecise definition of "human rights" and the unqualified condemnation of companies by the media and NGOs. "On a daily basis, we have safety rules, training, internal audits to meet internal regulations and, of course, a due diligence plan. But for the media, NGOs and human rights groups, all companies are the same. Total is being attacked for expropriating land from Ugandan farmers for oil production; we agree that it is an infringement of rights if it does not properly compensate these farmers. But not all due diligence cases are like that. More precise legal rules are needed," he argues.

Lafarge, Lundin Energy and Ericsson

Brabant also recognizes the complexity of the subject for lawyers: "When we talk about human rights violations, we often talk about offences abroad. Here it is indeed a question of making a French company responsible for human rights violations that have taken place abroad. We therefore have a whole body of rules that must be developed and on which we must question ourselves.”

Today, all eyes are on the Lafarge case and that of the two other multinationals in the judicial hot seat. On November 11, 2021, Swedish oil company Lundin Energy’s president Ian Lundin and director Alex Schneiter were indicted for "complicity in war crimes" between 1999 and 2003 in Sudan, a country ravaged by civil war. Three months later, following an extensive investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, telecommunications infrastructure provider Ericsson announced that it was being investigated by the US federal securities regulator, the SEC. The Swedish firm allegedly paid money to members of Islamic State in Iraq. "The big difference between these two cases and Lafarge is that the victims will not win their case in court and will not be compensated because these cases do not involve criminal responsibility of the companies," says Marie-Laure Guislain with regret.

CORPORATE RESPONSIBILITY: KEY DATES