When Gambia’s Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC) wrapped up in November last year, its end was greeted with excitement and hope for a much-awaited second part of the post-dictatorship justice response, mostly criminal justice and reparations. Which meant implementing the TRRC key recommendations.

“We executed our mandate almost flawlessly and submitted our final report and recommendations to the government, and we closed shop,” said Commission’s former executive secretary Dr. Baba Galleh Jallow, looking back on their work.

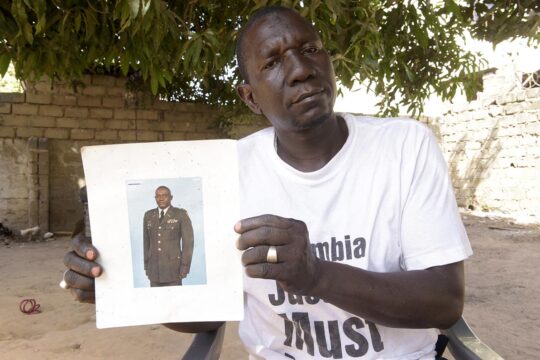

The TRRC inquiry has found former dictator Yahya Jammeh directly and indirectly responsible for arbitrarily killing of at least 232 people. One of those victims was Jammeh’s own cousin Haruna Jammeh, the father of Isatou Jammeh. Haruna Jammeh was killed by the former leader’s hit-squad called “Junglers”, according to one of its members Omar Jallow, who confessed before the Truth Commission in June 2019 to have participated in the execution. But like many other victims, Isatou Jammeh said the “excitement that greeted the TRRC’s work has faded”.

No government implementation plan

It has been 10 months—from November 25 to now—since Gambian president Adama Barrow received the TRRC final report on human rights violations under the Jammeh, and nine since he officially accepted it. In May the government issued a white paper accepting all but two of the Commission’s 265 recommendations. The Justice minister Dawda Jallow promised action would be taken on Jammeh-era crimes, announcing that letters had already been drafted to officials recommended to be sacked or banned by the Commission for involvement in human rights abuses.

But four months after the promise, none of the officials have been fired. Those who should have been banned from holding public office continue to work or are sent on administrative leave.

“Every time you have them at workshops, they say the same things. We are tired of hearing what the Ministry (of Justice) intends to do. Let us see these things so that we can believe something is going on,” said Isatou Jammeh.

The implementation of the recommendations of the TRRC — as envisaged by the former Justice minister Abubakarr Tambadou — is to be monitored by the National Human Rights Commission. The problem though, according to the rights commission’s chair Emmanuel Joof, is that “the government is yet to come up with an implementation plan,” that they could use as a checklist.

Lack of political will?

The relationship between President Barrow and the Jammeh’s victims has been a tough one. Quite often Barrow chose political expediency over justice. One such case was his attempt to forge an alliance with Jammeh ahead of the 2021 presidential elections—an attempt refused by the exiled autocratic ruler but accepted by the leadership of his party.

On September 22, Barrow faced Gambian lawmakers for his ‘state of the nation’ address. The televised address is expected to reveal his legislative and policy plans for the coming year. He had one sentence to say about the TRRC. “Following the submission of the TRRC report last year, Cabinet approved the relevant Government White Paper in May 2022 for implementation,” said Barrow. No word on justice for Jammeh-era crimes. No word on reparations. No word of any efforts being made to actually implement the recommendations.

And the person who welcomed him into the parliament – the House leader and the third most powerful political official in the country – was Fabakary Tombong Jatta, Jammeh’s longest serving majority leader in the parliament who, until recently, had campaigned for the TRRC report to be binned. Unsurprisingly his appointment by Barrow was criticized by the victims.

“There’s absolutely no political will otherwise it would not have taken nine months since submission of final report and 4 months since the white paper was issued – and still there’s no action or direction,” said Gambia’s leading rights activist Madi Jobarteh. “All we hear is the Minister of Justice lamenting the lack of capacity and resources and that the reparations bill will come in 2023.”

“No money”

At this point, the Ministry of Justice has also failed to produce a prosecution strategy or even decide on a model of a court to handle serious crimes cases. Everything, except the “selective implementation” of the Commission’s recommendations on the sacking and banning of public officials, is stalled.

Following a ‘Never Again’ march by victims in October 2021, the Ministry of Justice issued a statement promising to budget D150 million (about 3 million dollars), for the implementation of the TRRC recommendations for 2022. It didn’t come through. Instead, Jallow confirmed to the human rights committee of the National Assembly in June that they have no money to implement the recommendations for this fiscal year.

“Many of these recommendations require only simple reforms that do not require much money, if at all,” said former lead counsel of the TRRC Essa Faal. “These low-hanging fruits could be harvested. Such steps will show commitment and will reinforce the hopes and aspirations of many Gambians for justice in this matter. That could be a good start.”

Delayed reparations bill

After the sale of the assets of Jammeh, who lives in Equatorial Guinea, the Gambia government promised to pay D100 million (1,8 million dollars) to the TRRC reparations fund. Only D50 million were paid. In addition to this, Tambadou announced in August 2019 that Senegal had contributed D50 million to the TRRC Trust Fund. According to a source who got direct knowledge of the donation this money was from proceeds of the sale of over 2000 tons of Senegalese timber confiscated in the Gambia. When sold by the Gambian authorities, they sent D50 million to Senegal in December 2019, which were returned as Senegal’s contribution to the TRRC.

But it isn’t clear where the donation money went. “The timber sale was not yet completed at the time and the government decided to give out the D50 million from the Jammeh assets. Meaning that Senegal’s donation is still outstanding,” claimed a senior official of the Justice Ministry who does not want to be named.

By July 2021, the Truth commission has already paid a significant amount of reparations from the D50 million it had received. The TRRC full reparations assessment would require a pay-out of little over US$4 million, TRRC chairman Lamin Sise and his deputy Adelaide Sosseh said in a press conference on July 16, 2021. This leaves a revenue shortfall of US$3.3 million, including US$625,610 to be paid to families of West African migrants killed in Gambia in 2005. However, the government said it is working on a reparation bill to be tabled next year that will take care of the remaining reparations.

“The Ministry of Justice should have done a capacity assessment to determine what technical capacities are required for investigations, prosecutions, reparations, and other aspects of the implementation process,” said Jobarteh. “They should cost the entire TRRC recommendations so that there’s an indicative figure. This will help to determine what the government can provide and where the rest of the money should come from.”