JUSTICE INFO: Law professor Philippe Sands started the ball rolling in February with his piece in the Financial Times on creating an international tribunal to prosecute Russia for the crime of aggression. Ukraine started campaigning around this in April. Baltic countries and Poland pushed in particular directions. And now top officials of the European Union are joining in. So where are we now?

KEVIN JON HELLER: Well, we don't really know, which is part of the problem. There seems to be quite a bit of talk and very little actual action.

Ukraine clearly wants a mechanism of some sort. Probably because of the voices whispering in their ear, they lean toward the ad hoc model. But they've been very clear that they're open to the possibility of a hybrid tribunal based in Ukraine. You've seen people like [American Law Professor] Oona Hathaway argue that there would be constitutional problems with that. And the Ukrainians just keep saying, yeah, but it's a question of political will; if we want to do it, we can do it.

The European Union, too, seem to be leaning toward the ad hoc model. But again, like Ukraine, they have hedged their bets and said that they would consider either model, the hybrid or the ad hoc. We've seen a few states weigh in; the usual suspects like Liechtenstein. We’ve seen some of the states in Eastern Europe kind of supporting the idea. Interestingly, France is now coming out, I don't want to say robustly, but more than tepidly in favour of a mechanism.

We don't know who's involved with what, what they're actually doing, where the process is, much less what will actually happen.

It's very easy to say we want a mechanism. But it's very different to actually start creating a mechanism. We keep hearing rumours that somebody, somewhere – again, not much transparency – are putting together a resolution that would be introduced at the U.N. General Assembly (UNGA), because that seems to be something that everybody agrees on, that there has to be some kind of universal UNGA endorsement. But I haven't been able to find the text. It certainly isn't public. I've asked a bunch of people who are in a really good position to know if there is actually one circulating and they can't find it. Everything is kind of functioning as a star chamber. We don't know who's involved with what, what they're actually doing, where the process is, much less what will actually happen. So, the current state of play is very ill-defined.

Let's start with the difference between an ad hoc and a hybrid. An ad hoc tribunal seems to suggest it's actually U.N.-owned or set up via some other international body. A hybrid suggests it is essentially Ukraine-owned, but maybe with U.N. support. Or is there a further way of dividing those two that we should understand?

Your general summary is spot on. The difference is that there's really two different models that we would consider ad hoc tribunals. The first model is the one that you alluded to earlier, which is the Philippe Sands/Gordon Brown declaration, which really contemplated a treaty-based court, obviously including Ukraine, because that's necessary from a jurisdictional standpoint, but essentially a bunch of like-minded states banding together and ratifying a treaty. So very much like the International Criminal Court (ICC) but probably not on that scale and of course, just limited to the crime of aggression.

That model seems to have fallen out of favour to some extent, or it's getting less attention because of the second model. And the second model would be an agreement between Ukraine and the United Nations, much like the Special Court for Sierra Leone or the Cambodia Tribunal, something like that. The idea has always been for that one to have a UNGA resolution essentially authorising the Secretary General to enter into this agreement or just subsequently ratifying it.

My sense is that the U.N./Ukraine agreement, blessed by the General Assembly, has more momentum behind it at this point.

So that's on one side. On the other side is what I've been advocating, which is a hybrid court, along the lines of the Bosnian War Crimes Chamber, where you have the aggression court based in the courts of Ukraine, but with international elements applying: the international definition of aggression, both Ukrainian and international judges and prosecutors. I've advocated for the Council of Europe to sponsor that kind of hybrid tribunal. But it could be the European Union (EU), it could be the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). The E.U. and the Council of Europe are open to that mechanism and Ukraine too, although it does seem to be in second position.

So you have those three main models out there, two of which are ad hoc and one is a hybrid.

We have two of the big drivers of international criminal justice in the United Kingdom and the United States. And they have literally said nothing.

Do we have any sense of any other important countries who are really pushing this forward?

Well, I don't think we know. But the fact that we don't know is fraught with meaning to some extent. We have two of the big drivers of international criminal justice in the United Kingdom and the United States. And the fact that this has been going on now for about eight or nine months and they have literally said nothing, at least at a formal level, is hard to read as anything other than very tepid support at best or kind of complete disinterest or even opposition at worst. Again, I'm reading between the lines. But we have to look at their silence and think that it's meaningful.

We also had a quite curious reaction from the prosecutor of the ICC to suggest that this was not the best way forward, that it would be essentially diluting the international system. How do we understand that, since the ICC cannot deal with the crime of aggression in the Ukraine conflict, full stop?

And the prosecutor knows that. I should say that I'm speaking completely in my academic capacity and not as one of his special advisors. I don't have any privileged knowledge of exactly what's going on in his mind. I think the biggest concern for him is that spending all of this time thinking about a new kind of international mechanism or even a hybrid mechanism for dealing with aggression runs the risk of side-lining what, in his view, is the most important way to pursue Russian aggression, which is to amend the Rome Statute [the founding treaty of the ICC] to expand the jurisdictional framework of the court over aggression.

There isn't any a priori reason why efforts couldn't proceed along both tracks. There could be efforts to get states to amend the Rome Statute at the same time as efforts to create a new mechanism. But I think his concern is a valid one, which is that amending the Rome Statute is going to be pushed off of the stage and all of the attention is going to be on this new mechanism.

For him, I think the real, enduring legacy of this conflict could be an expansion of the jurisdiction that allows not just prosecuting Russian aggression, but all the other future acts of aggression that might be within the court's jurisdiction. Give us the jurisdiction over aggression as well, that's really what I think his point was.

We can pretend genocide and war crimes and crimes against humanity are not inherently official acts, right? We can't do that with aggression.

Then there is the question of immunity. There's a piece of Dutch academic advice which was directed towards decision makers where they said that there is no clear cut international legal practise on the extent to which state officials have functional immunity.

They raised questions about both functional immunity and personal immunity. They said that it's not clear, unlike for other international crimes, whether functional immunity applies to aggression. We can pretend genocide and war crimes and crimes against humanity are not inherently official acts, right? We can't do that with aggression. Aggression is different. There is that rule that one state shouldn't sit in judgement of another state. And maybe states would say that this is such an inherent act of states that there should be functional immunity for it. That issue does deserve more attention in the public domain than it has gotten.

What about personal immunity?

We know beyond a shadow of a doubt that personal immunity exists for heads of government, heads of state and ministers of foreign affairs. They are completely immune from the jurisdiction of a state in its own domestic courts. They can't prosecute them. They can't detain them. They can't arrest them. They can't search them. And to be fair, nobody really has a problem or disagrees with that idea. The real big question is, how does personal immunity function at the international level? And if we accept what the International Court of Justice (ICJ) said that in at least some international courts, personal immunity would not apply, then of all these mechanisms that we are discussing, to what extent would personal immunity be a problem? Or conversely, could any of these models of accountability mechanism for aggression set aside the personal immunity of Putin, of Lavrov, of whoever the head of state, or head of government is?

I understand why they want the Putins and the Lavrovs. But even if you couldn't get them because of personal immunity, there's still 99% of the leaders who are involved, who could be prosecuted.

Is the issue how international a tribunal is?

Yes, that is really the issue because [the ICJ] decision didn't tell us. But framing this whole discussion is a really important point that is obvious but seemingly forgotten: we're talking about three officials at most. You know, it's not functional immunity. It's not everybody in the government. It is only those three. Again, I understand why they want the Putins and the Lavrovs. But even if you couldn't get them because of personal immunity, there's still 99% of the leaders who are involved in the planning, preparation, initiation or waging of the invasion of Ukraine, who could be prosecuted.

We're only talking about three people. So we need to keep in mind the stakes here. They're not unimportant, but the future of aggression prosecutions doesn't hinge on what we think about personal immunity.

The question is, if an international court doesn't have to recognise personal immunity, what is an international court? And this is a very, very complicated doctrinal question, that very rarely gets any kind of systematic treatment.

The standard answer is basically just to recite as a mantra that [the ICJ decision] says international courts don't have to recognise personal immunity; an ad hoc tribunal for Russian aggression would be an international court; therefore, an ad hoc tribunal would not have to recognise personal immunity. QED. Let's all go home. They don't even really make any attempt to try to disentangle what is an international court.

If you take international law seriously, the bottom line is that any of these mechanisms would have to recognise personal immunity.

Without making it more complicated, what implications does this have for the potential design of a mechanism?

If you take international law seriously, the bottom line is that any of these mechanisms would have to recognise personal immunity. The only exception - and this is arguable - is if you had a UNGA resolution that was overwhelmingly supported by all the four corners of the globe, with states explicitly saying: we bless this tribunal and as part of the tribunal’s functions, heads of state or individuals entitled to personal immunity would not be able to claim immunity from its jurisdiction. If you had that, I think it probably works. It works if it's an ad hoc model. And frankly, I think it works if it's a hybrid model.

Essentially it needs a stamp of approval of a large number of states from a large geographical representation?

Yes, it's kind of like instant customary law. Basically, to have a customary rule, not every state in the world has to endorse a particular rule. It just has to be a very large number - and of course, courts won't tell us exactly how many is very large – and it also has to be widespread. It has to represent the world's legal systems, the world's geographic areas, the world's traditions. If you have that, and a court ended up prosecuting Putin, I probably wouldn't write a long blog post saying, ‘but he has personal immunity’. I would say this is untested, this is very new, and there's a strong argument that, legally, that is acceptable.

But I don't think anything short of that will work. And that's why you're starting to see more emphasis being put on the General Assembly resolution.

If I was the U.S. or the U.K., I would be worried. I think they understand that this is a dangerous road to go down.

The other element to pull out of the Dutch academic advice was essentially: be careful what you wish for, because if this does become ‘instant custom’ as you put it, then who else can end up being prosecuted for aggression? It can be your own leadership…

Absolutely. And I think it does explain some of the reticence of countries like the UK and the US. I mean, frankly, I've continually asked the people who really believe in the UNGA route, how many [states] do you need? How many do you think have to vote for this? Law professors Astrid Reisinger Coracini and Jennifer Trahan have argued that a successful resolution with 60 positive votes would be enough to strip Putin's immunity.

There's a lot more states in the Global South than there are in the Global North. If Global South states then decide, okay, well, we want to prosecute George Bush for aggression in Iraq, so we're going to get Iraq and the U.N. to enter into an agreement to create an ad hoc mechanism, and all of our other Global South buddies and us will get together and we'll pass a resolution and we'll say in that resolution, no personal immunity. And look, only 60 is required, that was the operating theory with the Russia tribunal. And they create a tribunal that has jurisdiction over George Bush.

That works, right? I mean, it's exactly the same legal rationale. If I was the U.S. or the U.K., I would be worried. The Global South is much more likely to get those kinds of numbers than the Global North is. I think they understand that this is a dangerous road to go down. An even more dangerous road to go down, though, would be the Philippe Sands and Gordon Brown model, which is just a couple states can put together a tribunal and call it international.

Isn’t that essentially what Nuremberg was, though? It was just a few states.

I'm a Nuremberg scholar. The reason there was no immunity is that the Allied Control Council was the government of Germany. And as the government of Germany they waived all of the immunity of its officials. But that's never going to be repeated. So I don't think that Nuremberg helps either way that much because it's such an unusual case.

What I'm also getting at with the Nuremberg question is that if Russia agreed to it or Russia was represented in some way, then any tribunal would be fine.

Absolutely. Because one of the keys to any kind of immunity is that immunity is not held by the individual. Immunity is held by the state on behalf of the individual. So if a state formally waives the immunity of its officials, there's nothing that official can do about it. The problem is, of course, in Russia, as long as Putin is the head of state, he's not going to waive his own immunity. But if he were to be overthrown by, say, a slightly more progressive Russian government and as part of making good with the West, they were going to offer him and Lavrov up, you know, as sacrifices, they could absolutely do that. If it's consensual prosecution, immunity doesn't become an issue.

Everything that I've been arguing is just a kind of a cautionary tale and a warning to think about what you might be doing.

Does it really matter what law professors have to say about this if there is political will? I mean, if there is political will, it's going to happen, isn't it?

Yes, it is going to happen if there's enough political will, for better or for worse. In some ways everything that I've been arguing is just a kind of a cautionary tale and a warning to think about what you might be doing. I have absolutely no doubt in my mind that at any international tribunal that was actually created, if a defendant like Putin claimed personal immunity before it, they wouldn't give him personal immunity. It doesn't matter if there's no legal argument at all for taking it away. I mean, no tribunal is going to say, okay, sorry, we don't have jurisdiction over our defendants, let's all go home. They won't. So if it gets that far, all of these legal issues and all the massively long blog posts saying this is an outrage won’t matter. They'll find jurisdiction. Which is why it's so important for me and for others who are more critical of the enthusiasm for institution building to be heard now. Because we're only useful insofar as we might make some states or some leaders or some influential people think twice about going this route.

You could end up with a resolution claiming to be able to fundamentally change the landscape of personal immunity based on maybe 70, 75 states voting out of 194. I think that would be really catastrophic for the legitimacy of a tribunal.

So now do we carry on in this limbo for some time and this just remains a discussion?

It's very hard to talk time frames. I don't think the creation of any kind of aggression tribunal is imminent. If Ukraine was much more interested in a hybrid model, they would be able to get it up and running much sooner because so much more would be in their control. And, if they did it there's no way that the West wouldn't be getting on board because they're so committed to promoting Ukraine's interests. But as long as we're talking about one of these much more difficult build-from-scratch international mechanisms, we're still at the stage of talking about what it might look like and how it might run, much less actually getting the money, building it, hiring the staff. I mean, this is a long process. It can be sped up with political will, but we're talking a pretty long timeframe and we have no defendants yet. So I think we're going to be in limbo for quite a while.

I do think the concrete efforts to create a tribunal will emerge sometime in the not too terribly distant future. I wouldn't be surprised if an UNGA resolution failed. It is also possible that it passes. You could end up with a resolution claiming to be able to fundamentally change the landscape of personal immunity based on maybe 70, 75 states voting out of 194. I think that would be really catastrophic for the legitimacy of a tribunal and would be even more catastrophic in terms of basically sending a message to most of the world that their views on these issues don't count. And I think that would be really harmful for the long-term prospects of aggression.

Can you imagine that we end up with a trial in absentia of a sitting head of state?

I would like to say it is beyond even my cynicism that a court like that would try someone like Putin in absentia. Just the idea that a bunch of essentially Western states could come together to create a tribunal that has the power to set aside personal immunity and then prosecutes a sitting head of state in absentia, would just doom aggression as a fundamental international norm. You will never get the Global South to ever take seriously the crime again. It would just be such a naked exercise of power that I'd like to say it's inconceivable. But you know, there are so many true believers out there that just any aggression prosecution of a sitting head of state is great, it could happen. I really hope it doesn't. I don't think it's likely, but it's not impossible.

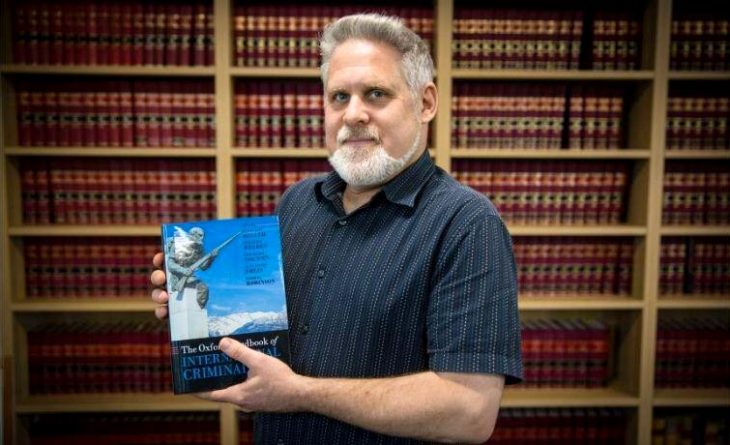

Prof. Kevin Jon Heller is currently Professor of International Law and Security at the University of Copenhagen’s Centre for Military Studies, as well as Professor of Law at the Australian National University. His books include “The Nuremberg Military Tribunals and the Origins of International Criminal Law” (OUP, 2011) and four co-edited volumes: The Handbook of Comparative Criminal Law (Stanford University Press, 2010), The Hidden Histories of War Crimes Trials (OUP, 2013), The Oxford Handbook of International Criminal Law (OUP, 2018), and Contingency in International Law: On the Possibility of Different Legal Histories (OUP, 2021). He is a special Adviser to the ICC Prosecutor on International Criminal Law Discourse.