JUSTICE INFO: What is the size of the War Crimes Department at Ukraine’s Office of the Prosecutor General today?

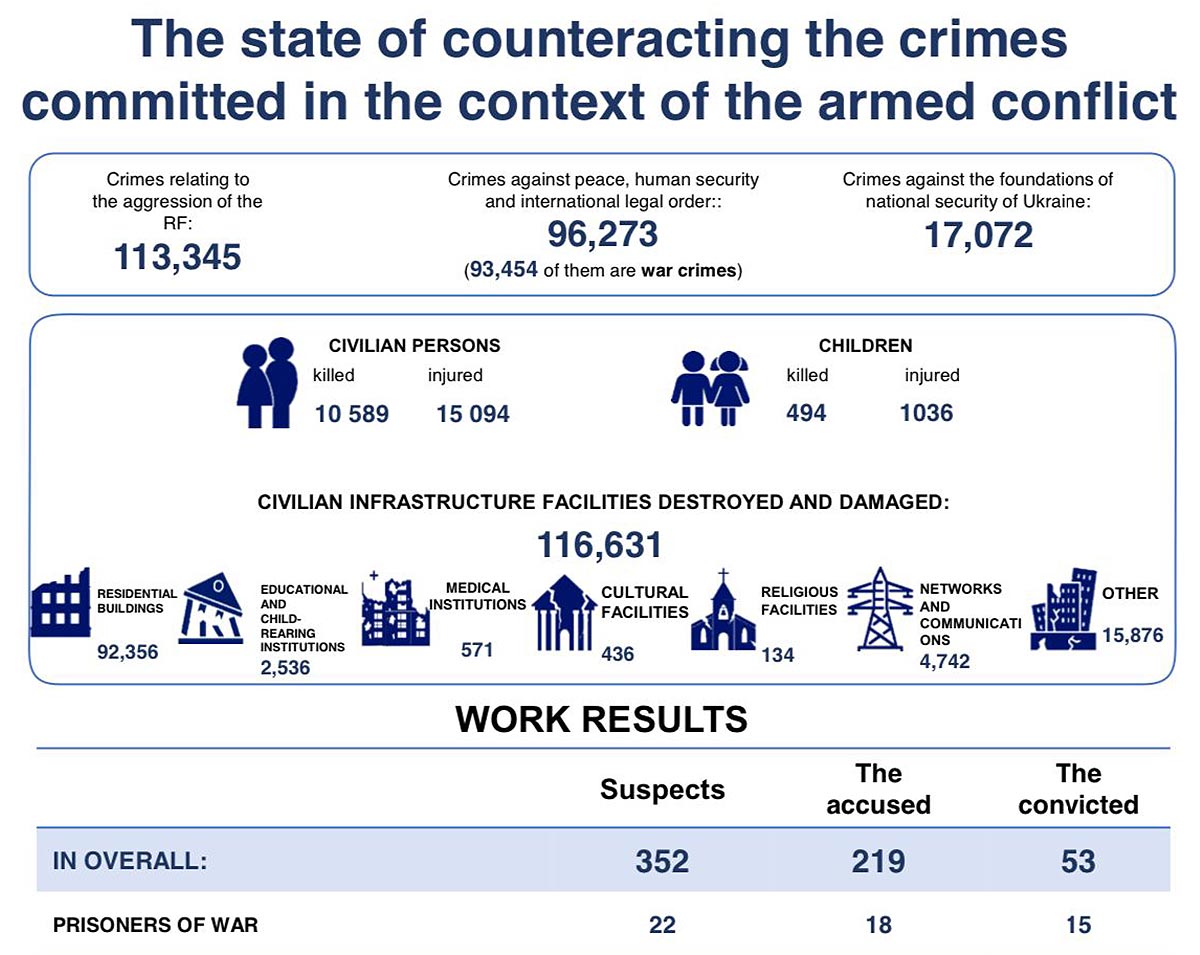

YURIY BELOUSOV: In total, we have 200 war crimes prosecutors working in the country. We have 100 persons working on war crimes at the Office of the Prosecutor General, including 82 prosecutors, and we have 120 prosecutors working on war crimes in the regions. In addition, a lot of investigations are done by other prosecutors because the scale of the crimes is so big that war crimes prosecutors alone can’t do the job. But we supervise all these investigations. As of today, we have 92,000 war crimes registered since [Russia’s] open invasion on February 24 last year. To collect evidence, we work with security services and with national police; they also have war crimes investigators who work as a team with war crimes prosecutors. It’s difficult to say because it’s changing, but 500 people may be working on war crimes full time.

We have some departments like the juvenile department at the Office of the Prosecutor General that investigates specific war crimes committed against children, or the ecological prosecution office that investigates crimes that do harm to the environment. They have around 20 or 30 prosecutors. Then we have several teams working on major crimes at the central office: one team is, for instance, on genocide, another on the crime of aggression or the attack on the Kakhovka dam [on June 6, the Nova Kakhovka dam in southern Ukraine was destroyed by an explosion causing huge environmental damage and dozens of deaths].

These are the main ones, who work on more than 90% of our cases. Our main task at the central office is to coordinate the whole system of war crimes investigations in the country.

We designed a strategy to prosecute international crimes in Ukraine for the next three years. In maximum two or three weeks it will come into force.

In your view, have you succeeded in bringing enough cases to trial up to now?

Let me first say that two years ago in Ukraine we didn’t have a war crimes investigative system at all [the War Crimes Department was initially created in 2019, focusing on Donbass and Crimea, then reorganised and strengthened after February 24, 2022]. We were investigating totally different types of crimes before the war. So our task was first to establish this system. We have established specialized teams at the Office of the Prosecutor General and in nine regions, and the national police and the security services also have. We have designed standards that we share with our colleagues, for everyone to be on the same page. Now we are working on a unified database that would put together the huge load of information on war crimes that we have accumulated. We are trying to introduce new IT solutions – Microsoft for example or other companies have helped us with instruments to analyse the data. We established good cooperation with the International Criminal Court (ICC) and with other countries. We now have 24 countries that have started their own investigations on war crimes in Ukraine. We give them evidence, we share information. We also have conducted a lot of training on international humanitarian law for our prosecutors and for our investigators.

And then, we designed a strategy to prosecute international crimes in Ukraine for the next three years. I believe that in maximum two or three weeks it will come into force. The strategy has very clear goals on what should be done in Ukraine. We definitely should do our best not to give any war criminal a chance to avoid punishment. Even if it takes years.

We have a systematic approach. We established active collaboration with NGOs and with our international partners, to share information with each other, not to duplicate. For example, if we know that one country started their own case, we are trying to help them with as much information as possible. We cooperate with the ICC on a daily basis: if we see they are interested in a particular case, we try to do our best to help them collect proper evidence, to speed up the prosecution. From the selection of the case [against Vladimir Putin and Maria Lvova-Belova] to the arrest warrants [released last March] it took the ICC only five months. This never happened in history; it usually takes years for the ICC to reach such a result.

What is your policy if the ICC or Germany, for instance, wants a case - how do you decide?

Every country is independent. If Germany or Italy start their own investigation, they are independent to select whom to prosecute, which evidence to select. But at the same time, we just tell them: tell us which case and who you are interested in, we will give you all the evidence we have, and we will stop our own investigation against the same criminal. Because a double prosecution would be a violation of [the accused’s] rights.

99% of the cases will be investigated in Ukraine, we understand that. This is our job. We coordinate through the platform of Eurojust. It’s a special entity in the European Union that represents prosecutors’ offices. We have already conducted several meetings with countries that have started their own investigation. The last one was in December last year, where I participated with the prosecutor general. With the ICC there is no specific rule, but if the ICC decided to prosecute someone, we would definitely stop our procedure. That’s how we are trying to make war crimes prosecutions in Ukraine effective globally. This is our strategy.

Ukraine is one side of the conflict and our decisions, our verdicts, would always be criticized. We want other jurisdictions to prosecute.

Is this strategy driven by the fact that you have limited resources, or by other principles?

Resources are important, but this strategy is also important for legitimacy. Because Ukraine is one side of the conflict and our decisions, our verdicts, would always be criticized – that we are not objective, that we are part of the conflict – we understand these potential criticisms. That’s why we want other jurisdictions to prosecute. Everybody remembers the case of the MH17 Boeing [in 2014, a Malaysia Airlines aircraft was shot down over Ukraine’s Donbas region, killing all 298 civilians on board]; it was a case that was prosecuted by a national court in The Netherlands, but its verdict [in November 2022, a Dutch tribunal found three Russians and one separatist Ukrainian guilty of shooting down the plane] was resonant for the whole world. Ukraine helped The Netherlands as much as possible to collect evidence.

Limited resources is one of the reasons, but the legitimacy and political global importance is important for us. So it’s also a political perspective: the more countries start their own prosecutions, the more the whole word would see that it’s not just a matter of Ukraine. It’s not just Ukraine which is blaming Russia. International crimes is not just a word; it means that they are so severe that it matters to the whole world and the world should react.

Prisoners of war are less than 10% of all of our prosecutions. The rest are in-absentia investigations.

If we consider trials in the presence of the accused, we have seen limits in terms of their number and level of responsibility. Is this connected to another priority, i.e exchanging prisoners of war?

No, no, no, it is important to mention that we try to prosecute different levels of potential Russian war criminals. We have a big case on the crime of aggression, with already more than 170 suspects, top leaders of the Russian Federation, members of parliament, top chiefs of the Ministry of Defence, heads of intelligence, and others. We already have verdicts from our courts against several members of the parliament who made the decision to initiate the war against Ukraine or to make part of Ukraine part of the Russian territory. The crime of aggression is a separated and big investigation and we are working on that [see chart in PDF below].

Without waiting for an international tribunal to be set up, the Ukrainian Prosecutor General has so far issued 312 indictments against political and media figures and senior members of the Russian security apparatus. To date, twenty Russian MPs have been tried in absentia and convicted in this major case for Ukraine.

We mostly have soldiers and lower officers in our hands, because they are the ones we could physically capture. Generals, members of parliament and the Minister of Defence [of Russia] are not in Ukraine. We have thousands of prisoners of war, but we don’t prosecute each of them, we have a screening procedure. If we see that a particular prisoner of war is involved in a war crime, then we start prosecution against him. If not, he is kept in a camp for prisoners of war which Ukraine has established according to the Geneva Conventions, and then exchanged against our own prisoners of war. That’s why in our indictments, prisoners of war are less than 10% of all of our prosecutions. The rest are in absentia investigations that we conduct without the suspects in our hands. But we believe that this is just a matter of time.

Why?

Because justice could wait. Ukraine’s legislation allows us to have a sentence in absentia. It already helps us to limit the movements of this person. She or he already can’t leave Russia because he/she would be arrested, or it helps to find his or her assets abroad and to seize these assets. That’s why we use in absentia cases. It would definitely be better if these people were physically in court, but in the course of an armed conflict it’s not always possible.

If we see that we have suspicion that a person has committed war crimes, the Office of the Prosecutor General can prevent it from benefiting from a prisoner exchange.

Regarding the exchange of prisoners, do you have a word to say as a prosecutor?

Yes, sure, and I was leading the group which was set up to design legislation [on prisoner exchange] since the very beginning of the open invasion. We are not the ones who make exchange but we are the ones who check everyone who is claimed for exchange. If we see that we have suspicion that a person has committed war crimes, the Office of the Prosecutor General can ban the exchange. Our task is also to prevent exchange of war criminals, and we have a list of people we prohibit for exchange.

Can we have an idea of the number of cases that might be brought to court in the next months?

It’s difficult to say how many. In Ukraine’s legislation, we should notify the person with a notice of suspicion, then we send the indictment to the court, then the court issues a warrant. [see chart below].

The attack on the Nova Kakhovka dam had an enormous impact. Do you think this is a case that should stay in Ukraine or go to the ICC?

At the moment, it’s difficult to say. We are definitely ready to prosecute. But at the same time, the ICC is also interested in this case. That’s why we will definitely be in negotiations with the ICC. I think they would be interested in top commanders. Our task is to prosecute everyone who is involved. That’s why if the ICC should be interested in a particular person we would not take him to our courts. I think this case would be, let’s say, “cut in pieces”.

We see the ICC as our partner. Their task is to prosecute top leaders of the Russian Federation. But 99% will definitely be prosecuted by us.

How do you think Ukrainians see the fact of prosecuting war crimes in times of war, what does it mean to them?

You know, everyone is looking for justice, but our task is to show that we are not wasting time and that we are doing our best to collect evidence wherever we can and prosecute all who are involved. It’s also important that our Office of the Prosecutor General is changing our approach. Now it has established a special coordination centre for victims and witnesses of war crimes. It’s an absolutely new approach and this centre is to support victims, cooperate with other agencies, and provide legal, psychological, and social care for victims.

Our militaries are fighting, they have their own front, they have their own battle. But we, as prosecutors and investigators, have our own battle. It’s a legal battle. And we can’t lose this battle. Our task is to collect evidence and do it in the best possible way, in accordance with international standards, not give any chance to any Russian criminal or whoever is committing a war crime in Ukraine to get away with punishment. That’s our front. We are trying to persuade the society that we are doing our best to win this particular legal battle.

At the moment, we already have an effective system, we have well trained people, we have perfect cooperation with our international partners. They help us to get the information in the fastest way, to share this information, and I am very proud that in the past year our team managed to significantly increase the quality of these war crimes investigations.

At the same time, we are trying to persuade our citizens that it could take time. Justice doesn’t come the next day. When you look at the Nazis in the Second World War, the whole world was looking to get them 50 or 60 years later. We see the ICC as our partner, we trust that they are doing their job, which is to collect everything in the most objective way. Our task is to help them. Their task is to prosecute top leaders of the Russian Federation. The rest will be prosecuted by us or by other countries. 99% will definitely be prosecuted by us.

YURIY BELOUSOV

Yuriy Belousov, 46, has been nominated as head of the War Crimes Department in Ukraine’s Prosecutor General’s Office on May 24, 2022 . Previously, he was head of the Department for Combating Violations of Human Rights in the Law Enforcement and Penitentiary Sectors and the PGO’s specialized Unit for Combating Torture. From 2016 to 2019 he was executive director of the Experts Centre for Human Rights, an NGO working on criminal justice and human rights in Ukraine.