“Together with many other countries across the world, [we have] referred this whole Israeli government action to the International Criminal Court,” said South African president Cyril Ramaphosa, on a visit to Qatar last week. The following Friday a press release from ICC Prosecutor Karim Khan announced that he had received a referral of the situation in Palestine from five member states of the Court: South Africa, Bangladesh, Bolivia, Comoros, and Djibouti.

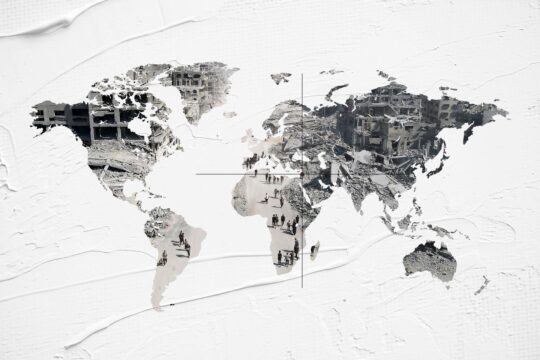

This was the latest indication of a number of states beginning to flex their diplomatic muscles over the way that Israel has conducted its war in the Gaza Strip. With more than 10,000 Palestinians reported dead, apocalyptic scenes of destruction around Gaza City and a population suffering in the south with very limited humanitarian aid, some world leaders have become increasingly critical of Israel’s right to pursue the infrastructure and fighters behind the surprise Hamas attack on October 7 that left 1200 Israelis dead and more than 200 taken hostage.

The ICC prosecutor’s response so far has been to make his position known through limited media statements outlining his office’s jurisdiction and warning all parties of potential prosecution. Shane Darcy, deputy director of the Irish Centre for Human Rights in the School of Law at the University of Galway, notes Khan deploys “very, very flowery language” in these pieces and while “he puts the parties on notice that there are legal obligations, it's very, very heavy on the rhetoric.”

There’s no sense of increased activity in the investigation. Since that officially opened in 2021 – after five years of “preliminary examination” – the ICC has been regularly cajoled and criticised by human rights activists for its very slow approach. The state of Palestine has both referred the full situation to the court in 2015 and continued to lobby the prosecutor, delivering reams of analysis of alleged crimes against humanity and war crimes. Palestinian NGOs have provided countless reports and documented human rights violations. Butthe court has been “something of a cold house for Palestine”, says Darcy. In its latest report on outreach in Palestine the court’s registry describes the frustration of victims expressed to their legal representatives : “Clients have been profoundly disappointed, even before the current crisis, at the complete absence of the Court.” Yet, against the pressure, the prosecutor is still calling on the parties to comply with international humanitarian law, rather than declaring his readiness to proceed. “You're the person that is the gatekeeper to the ICC in this context, because you already have an active investigation,” says Darcy, “the ball is literally in your court now.”

“There's no reason not to proceed in a legal sense,” he continues, “I think it could, in fact, be the death knell for the court if we don't see action in this particular context.”

Why South Africa is leading the charge

Belgium has declared its intention to provide more funding to the ICC, and Ireland has shown support. But outside of that small group of “Global North” states, most diplomatic unease has come from “Global South” countries. The comparison is striking with the reaction to Russian aggression against Ukraine, says Alonso Gurmendi Dunkelberg, lecturer in international relations at London’s Kings College, where 43 states referred the matter to the ICC. He believes that this may be an opportunity for Global South states to use their increased political power to “become international law enforcers”. This is now a “moment of crux, like a crossroads for the Global South”. Every single member of these emerging powers, he says, has a history of colonialism and dealing with imperialism and they have seen how more powerful states have argued “the rules only apply to me and not to you”. Brazil is an example, he says, of principled reaction “opposing disproportionate harm against civilians by Israel” which has seen them actively promoting resolutions at the U.N. Security Council on Israel’s actions. This is part of the “transition from ‘quote unquote’, small country to emerging power,” Gurmendi says.

Gerhard Kemp, professor of criminal law at UWE Bristol law School, agrees that Ramaphosa’s ruling party in South Africa, the African National Congress (ANC), has “certainly regarded international law as a tool that they can use to restructure the power structures of the world. One common theme has always been the matter of consistency and Western hypocrisy.”

South Africa’s position has drawn from its traditional support for liberation movements. “The ANC has a very long history of supporting the Palestinian cause, so it has to be seen through that prism,” says Kemp. Kemp anticipated South Africa’s latest move “to build up a group of like-minded states, as we've seen last year with [those] taking the matter of Ukraine in support of the ICC jurisdiction”. But such a movement would not have access to the resources that the United Kingdom and European states have been able to offer the Prosecutor in his efforts to investigate Ukraine.

Double standards

The key assessment of the ICC’s seriousness of approach will be “to see concrete action,” says Kemp. The prosecutor’s recent op-ed suggested that his standard for issuing indictments would be if the evidence “reaches the threshold of realistic prospect of conviction”. That is the promise he had campaigned on to be elected by ICC member states as prosecutor. But “that's not the standard that he is required to apply by the Rome Statute,” Darcy points out, “and I haven't seen evidence that's the standard that was applied in applying for arrest warrants in Georgia or in his statement on welcoming the arrest warrants for Vladimir Putin and Maria Belova.”

Inevitably that makes observers concerned: “I'm curious as to whether he is setting himself up not to be able to issue an arrest warrant in some ways,” says Darcy. In addition, Khan’s decision to deprioritise his office’s investigations of alleged US crimes in Afghanistan and his predecessor’s decision on alleged UK crimes in Iraq reinforces fears that he may not be prepared to “stand up to those powers,” says Darcy. “I think it'll be highly problematic for the future of the court if it does not proceed in this context, given the longstanding nature of the Israel-Palestine conflict, the longstanding occupation. We see the language of apartheid being used in recent years; we now see ethnic cleansing, we see talk of risks of genocide taking place as well.”

“Palestine really is the final test for a country like South Africa,” agrees Kemp. “If this time around, there's going to be no action, then I think it's difficult to see if even South Africa would stay on in the ICC. Palestine is a make or break case study.”

In recent days there has been an additional flurry of public announcements of communications from NGO’s, both Palestine-based and from Europe and the United States, aimed at pressurising the court. In fact Khan has noted that his office now has “a significant volume of information and evidence,” including material submitted via the recently established secure platform called OTP Link.