On December 29, 2023, South Africa filed a case before the International Court of Justice (ICJ), alleging that Israel had violated its obligations under the Genocide Convention concerning the Palestinians in the Gaza Strip. South Africa also sought provisional measures, meaning that parties may request urgent measures to prevent imminent harm while the case is pending. A decision on the provisional measures is expected today, January 26.

It is the first time that Israel is on trial before an international court.

In the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, law and legal institutions have been extensively mobilized at both national and international levels. The Israeli High Court of Justice through Universal Jurisdiction, up to the ICJ and the International Criminal Court (ICC), lawyers on both sides have demonstrated creativity over decades. For both parties, legal institutions have been perceived both as tools for legitimization, and, simultaneously deemed politically biased and ineffective. At the international level, criticism of double standards has proliferated, yet institutions continue to be actively mobilized, sparking media and public debates: In the ICJ on the 11 and 12th of January, the pressroom was filled with Israeli journalists from both written and TV media, underscoring the importance with which Israel approached the proceedings.

This procedure, framed through the lens of genocide, was the only avenue to secure standing before the ICJ. However, the limitation of this procedure is that the law governing the conduct of hostilities, including allegations of war crimes and crimes against humanity, will not be examined, as the ICJ's jurisdiction is confined to the Genocide Convention. This implies that if the case is rejected on its merits, it might be viewed in Israel as alleviating any responsibility.

The choice of Judge Barak

Currently, an advisory opinion is also pending before the ICJ. Submitted in early 2023 by the UN General Assembly, it requested the court to address the legal consequences arising from the policies and practices of Israel in the occupied Palestinian territories. In these proceedings, 57 states have decided to intervene and submit their observations on the matter. They are scheduled to be heard on February 19th 2024. Twenty years ago, in 2004, the ICJ already issued an advisory opinion concerning Israel/Palestine, on the legality of the wall constructed by Israel in the occupied Palestinian territories. At that time, Israel chose not to participate in the proceedings. This decision faced internal criticism, notably from the former President of the Israeli Supreme court, on the ground that it missed an opportunity to justify its actions in light of international law. This may explain, in part, why Israel has opted to participate in the proceeding this time.

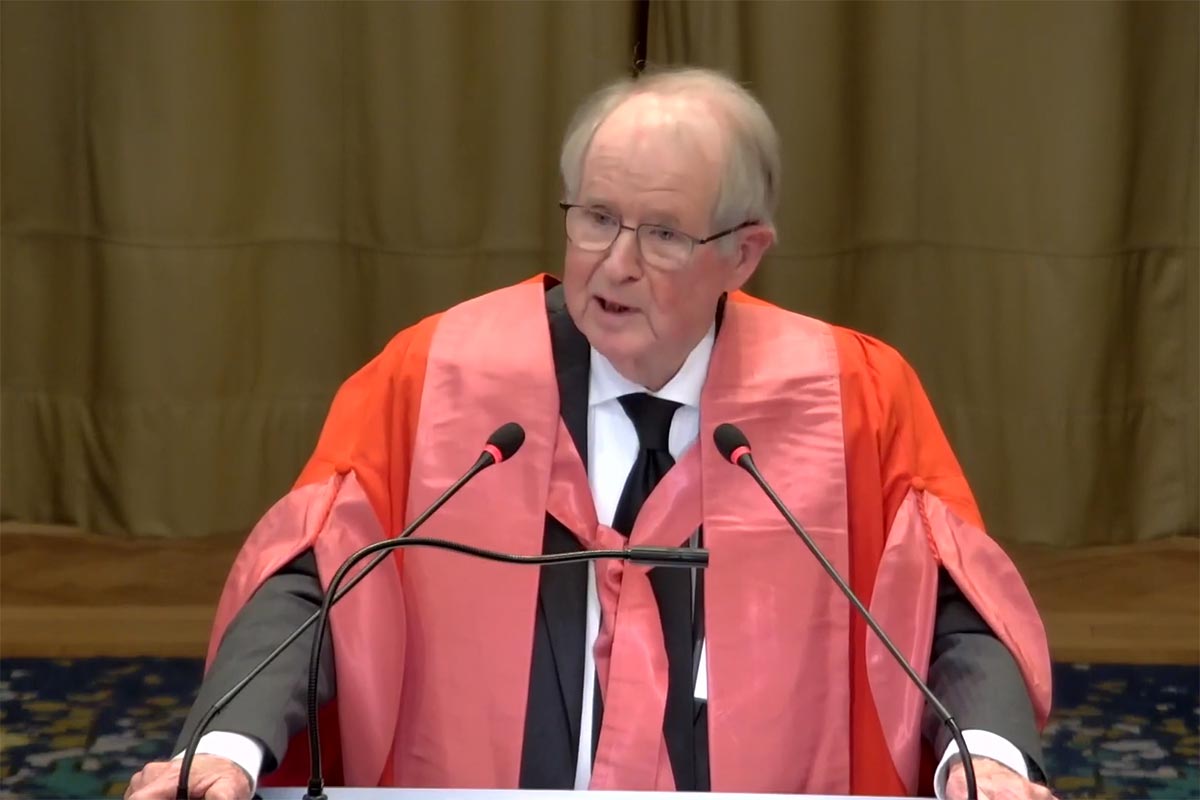

Both South Africa and Israel had the right to designate ad hoc judges from their respective countries: Judge Dikgang Ernest Moseneke and Judge Aharon Barak.

The nomination of Judge Barak should be put into context: Between the submission of the case by South Africa and the setting of the hearings two weeks later, the Israeli Supreme Court rendered an decision that annulled the initial step of a contentious judicial reform that posed a threat to destabilize Israel’s democratic structure. The ruling faced strong criticism from the government. This long-awaited decision arrived following a year of political turmoil in Israeli society in which an ‘pro-democracy’ camp was mobilized, with the active participation of Judge Barak, saying: “If being executed could put an end to this drastic reform, I am ready to face the firing squad." In the 90s, Judge Barak introduced through jurisprudence a constitutional framework for the protection of fundamental rights in a country where no constitution existed. The proposed government reform specifically targeted that competence, leading to portray Barak as "the enemy of the people". Against this tense backdrop, the Prime Minister decided to nominate Barak as the Israeli ICJ ad hoc judge. While Judge Barak enjoys a high international reputation, human rights lawyers have accused him of legitimizing Israel's occupation. Sitting on this trial, a notable professional achievement, could provide an opportunity for him to reestablish his legal authority, detached from any obligation to be apologetic to Israel’s Prime Minister.

The old ties between South Africa and Palestine

In the case against Myanmar brought by The Gambia the Court ruled that any state party to the genocide convention could bring a claim without being directly affected by such alleged violations. There is an increasing trend where African states ('the Global South'), are actively asserting a role in pursuing justice “in the name of humanity”. South Africa's international lawyers have maintained a longstanding alliance with the legal representatives of the Palestinian Authority and Palestinian NGOs. This collaboration extends beyond professional and academic connections and is rooted in the historical struggle against apartheid – a significant aspect of the current Palestine investigation at the ICC. For example, John Dugard, one of the senior lawyers in the South African legal team, is a former Special Rapporteur on Palestine, and a figure of the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa. He was part of the legal team advising the Palestinian Authority to submit an ad hoc recognition of ICC’s competence already in 2009, a move considered judicially avant-garde at that time.

As argued by Line Gissel, a Professor at Roskilde University, what is particularly interesting is that South Africa itself suffered from being governed by a racist government in its apartheid era and has overcome this. The analogy is compelling: Israel is presenting criticism of its violence as a threat to its existence. However, it is possible to separate the state from its violence, as South Africa did in the 1990s. South Africa still exists even after dismantling its apartheid state.

Revisiting the genocide definition can be tricky

Genocide is legally defined by the 1948 Convention as the commission of acts with the intention to destroy (in whole or in part) a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group. This intent can be inferred from explicit policies of political and military decision-makers or, as developed by jurisprudence, deduced from the acts of the state. The obligation pertains to the prevention and repression of genocide.

The Convention envisioned the creation of an international criminal court, which materialized 50 years later. Notably, the Rome Statute of the ICC adopted the same narrow definition of genocide as outlined in 1948, encompassing only four groups and excluding others. This contrasts sharply with the evolving definitions of war crimes and crimes against humanity in the Rome Statute, indicating a deliberate effort by states to maintain a high threshold for the definition of genocide.

Consequently, it is not surprising that the ICJ has historically favored a rather restrictive interpretation. For example, on the intention, in the absence of direct proof of such intent the court ruled that if the intention is to be deferred from the acts, then it can be done if this is the sole explanation.

However, very recently, a group of six Western states – France, Canada, the UK, Germany, Denmark and the Netherland – in a legal opinion submitted in the Case of Myanmar in November 2023, just a few weeks before the South African application, proposed to introduce a more “balanced interpretation” to the convention, particularly regarding how intent can be inferred from acts. Their legal position, based on the jurisprudence of the ICJ and international criminal tribunals, asserts that contextual elements, including the scale and nature of atrocities, supports a broader discretion in determining genocidal intent through inferred acts.

As noted by Kerstin Carlson, professor at the American University of Paris, these legal conversations are part of how jurisprudence develops and can be integral to judicial decision-making. While presenting this stance, the states' legal advisors considered not only Myanmar but also the potential ICC arrest warrant against Putin. Intriguingly, just weeks later, it became legally relevant in a less politically convenient case — the case against Israel. This could potentially expose their own contradictions regarding how genocidal intent should be legally determined. Indeed, UK, Canada and the US have rejected South Africa accusation of genocide. Germany, has announced that it would intervene in the proceeding in support of Israel. In France, the new Minister of Foreign Affairs stated at the National Assembly that “accusing the Jewish State of genocide is crossing a moral threshold ... one cannot exploit the notion of genocide for political ends”.

As the legal advisors of these states know well, unlike political battles, the law aims to establish a stable framework applicable to various situations. What was ruled yesterday remains applicable today, even if the political context has changed. In this sense, once the ICJ process is underway, it represents a rare moment when the law can prevail over politics, at least within the wall of this forum.

The South African plea

Provisional measures necessitate a much lower threshold of evidence, only prima facie evidence indicating that the claim is plausible. The requested provisional measures include an immediate suspension of Israel's military operations in Gaza, prevention of genocide, avoidance of specific acts, and protection of the Palestinians' conditions of life. “Genocides are never declared in advance. But this Court has the benefit of the past 13 weeks of evidence that shows incontrovertibly a pattern of conduct and related intention that justifies a plausible claim of genocidal acts,” pleaded a South African lawyer in the hearing at The Hague two weeks ago.

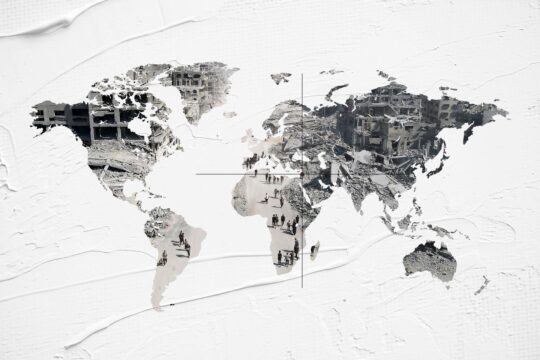

In support of its application for provisional measures, South Africa's first lawyer provided a detailed account of the acts, including killings, prevention of humanitarian assistance, destruction of livelihoods, and starvation. The presented facts aimed to establish the systematic nature of Israel's military attacks, which involved mass displacement, the intentional creation of conditions leading to a slow death, and a clear pattern of conduct targeting family homes, civilian infrastructure, and causing extensive destruction in Gaza. The lawyers supplemented their arguments with visual evidence profoundly distressing.

Regarding Israel genocidal intent, two arguments were advanced. First, South Africa argued that Israel's genocidal intent toward Palestinians in Gaza could be deduced from the acts, which form a calculated pattern of conduct indicating a genocidal intent. Second, South Africa presented a significant amount of quotations official statements (p 33-40), enumerating explicit intent declared by the highest political and army echelons to the soldiers on the grounds. Civil society is also involved in such collection. For example, an exhaustive collection of statements has been conducted by an NGO named Law for Palestine, which has established a detailed Database of Israeli Incitement to Genocide. John Dugard, of the South African team, sits on its board of trustees.

The Israeli plea

Israel mobilized top Israeli and foreign professors and lawyers, including, quite surprisingly, Professor Benvenisti, a former professor at Tel Aviv University who is currently at Cambridge. He is known for his strong criticism against the Israeli army's violations of international humanitarian law, as highlighted in his seminal book "The Law of Military Occupation". The main pleading lawyer was Malcolm Shaw, whose book on international law is studied in leading universities. He appeared with his British wig.

Israel claimed that there is no prima facie jurisdiction based on three arguments:

First, the lack of genocidal intent: Israel described the October 7th attacks by Hamas and their consequences, maintaining that all subsequent acts were aimed at protecting Israeli citizens and defeating Hamas. Regarding the statements collected, Israel contended that these do not represent the state's policy and were only random personal remarks. Second, self-defense: Israel’s lawyer emphasized that “the rights to be protected in the provisional measures procedure cover also the rights of Israel to act to defend itself and its citizens”. Third, Israel also raised a technical issue, arguing that there was no dispute between Israel and South Africa under the Genocide Convention at the time of submission of the application, as alleged by South Africa and as required for prima facie jurisdiction.

Parallel proceeding at the ICC

On November 17, 2023, a month before submitting the case to the ICJ, the Office of the Prosecutor of the ICC received a referral of the Situation in the State of Palestine from South Africa, along with Bangladesh, Bolivia, Comoros, and Djibouti. This referral reinforces an investigation initiated on March 3, 2021, that include the October 7, 2023, terror attacks by Hamas and Israel’s repost.

The ICC has jurisdiction as Palestine ratified the Rome Statute in January 2015. Several lawyers from South Africa’s legal team had previously advised the Palestinian Authority in the long legal saga on admission at the ICC or in previous ICJ advisory opinion. This suggests a continuity of legal representation and expertise and underscores the international collaboration and support that the Palestinian Authority has garnered in pursuing its legal claims.

The ICC Prosecutor's Office has confirmed that the investigation is a priority for its Office. In December 2023, the ICC Prosecutor visited Israel and Palestine, meeting with victims on both sides. Notably, Israel permitted this entry following demands from civil society and legal representatives of victims and hostages' families — a departure from previous instances like the Goldstone mission, where fact-finding missions were denied entry.

Given the current situation, where it seems that Israel’s Prime Minister Netanyahu is willing to prolong the war for personal political survival, potentially leading the country towards more violence and international law violations, ICC intervention, in collaboration with internal opposition and Israeli pro-democratic forums could be instrumental in assisting in dismantling a government that has delegated increased power to far-right religious ideology, leading to an ongoing authoritarian transformation. Drawing on the ICC's role in Colombia, I have previously argued that a transitional process can be a way of foreseeing a constructive role for the ICC in the Israeli/Palestinian context.

Sharon Weill is a professor of international law at The American University of Paris and affiliated as associate researcher at SciencesPo Paris (CERI). As a socio-legal scholar, her research is focused on the relationship between international and national law and the politics of international law. She is the author of the book The Role of National Courts in Applying International Humanitarian Law (Oxford University Press, 2014) and co-editor of the book Prosecuting the President - The Trial of Hissène Habré (Oxford University Press, 2020).