On Tuesday October 14, after 11 years of painstaking investigation, Belgian judicial authorities finally decided they had sufficient evidence to refer 55-year-old Liberian Martina Johnson to the Ghent Assize Court. Johnson is suspected of having committed serious crimes during the first Liberian civil war (1989 – 1996) as a presumed commander in the National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL), a rebel group close to former President Charles Taylor.

“It was clearly about time, and we will be all the more relieved when she faces the Assize Court,” Luc Walleyn, lawyer for two civil parties (aged 50 and 52), told Justice Info. A third plaintiff died during the proceedings, which suffered significant delays and possibly lack of will on the part of Belgian authorities.

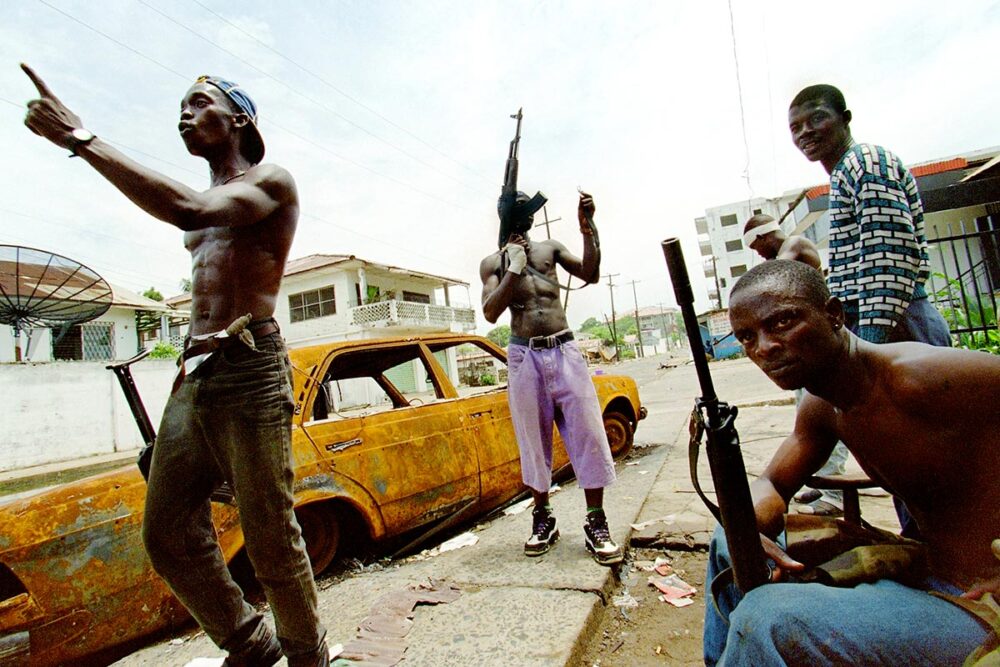

Three complaints were filed against Johnson in Belgium in 2012. She was arrested two years later in the Flemish region, where she had settled just before Taylor’s fall in 2003. These complaints relate particularly to abuses committed on October 15, 1992 during “Operation Octopus”, the NPFL assault on Liberia’s capital Monrovia. Hundreds of civilians and foreign aid workers lost their lives in this attack. Johnson is accused of having personally mutilated and tortured her compatriots. She has denied these allegations. She was indicted in 2012 and placed in pre-trial detention, first at her home under electronic tagging, then on bail in 2015 under strict conditions, notably that she is not allowed to leave the country.

2022: the investigation moves forward

It was not until 2022 that the Belgian authorities travelled to Liberia in a rogatory commission to hear witnesses, causing many concerns for both the defence and civil parties. The civil parties feared the death of key witnesses for both prosecution and defence, 30 years after the first civil war.

“There was a series of rogatory commissions in various countries -- the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Norway, Sierra Leone -- to meet witnesses and gather documents, photographic material from journalists and testimonies collected as part of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission [of Liberia],” says plaintiffs’ lawyer Walleyn. “This was also to recover some files from the Special Court for Sierra Leone. Two years ago, they finally went to Liberia to hear a series of witnesses over several weeks.”

According to our information, between 30 and 40 witnesses were heard by the police officers sent there. Belgium had hoped to question Taylor about his relationship with Johnson, but he refused to be interviewed. With all these elements, hearings of witnesses from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and Special Court for Sierra Leone, the investigation file runs to some 10,000 pages.

“These rogatory commissions clearly had to be done, and my clients and I were very frustrated by the delays,” adds Walleyn. “We put pressure on several occasions for this mission to Liberia to be carried out, and it has finally been done.”

Johnson’s lawyer Jean Flamme is less enthusiastic, saying that his list of 32 witnesses was not taken into account during this mission. “The witnesses were ready, but they were not heard,” he told the Dutch-language press. According to the criminal lawyer, the other witnesses are “unreliable” and those he had identified would have been able to testify that his client was in a different region from where the alleged crimes were committed.

Unanswered letters rogatory

Belgium had sent three letters rogatory to the Liberian authorities. All of them went unanswered, according to the federal prosecutor’s office in 2020. These unanswered requests surprised many, since in 2019, France and Finland were able to conduct investigations on the ground as part of judicial inquiries opened well after Johnson’s indictment in Belgium.

Belgium’s inaction in this investigation is said to be the result of several factors. Firstly, there was the risk to police officers travelling to a country affected by the Ebola virus and then by the Covid-19 pandemic. International borders were closed and restricted for many months. In a closed-door hearing during the proceedings, a federal prosecutor also cited lack of resources to carry out the mission.

The Belgian investigation team assigned to the Johnson case was also understaffed, according to a source close to the case. On top of that, its members were called to work on the terrorist cases that hit Belgium from 2016 onwards. And time was also needed to translate all the hearings into Dutch, the language of the proceedings.

War crimes and crimes against humanity

This has now been done, and all the evidence gathered by the police and magistrates was presented on September 30 to an investigating chamber within the Ghent Court of First Instance.

Belgium can prosecute individuals suspected of crimes and offences committed in a foreign country if it can be proven that they have a lasting connection with Belgium. Johnson arrived in Ghent in 2002, where she married a Belgian man of Liberian origin and had a child. This connection therefore exists.

In its closing arguments, the federal prosecutor’s office requested that the defendant be referred to the Assize Court for war crimes and crimes against humanity. According to a source close to the case, the federal prosecutor also called for Johnson’s arrest to prevent any attempt to evade the proceedings. On October 14, “the chamber referred the case back to the federal prosecutor’s office, which will shortly refer it to the indictment division with a view to sending the case to the Ghent Assize Court,” the federal prosecutor’s office said in a statement. “The chamber did not accept defence arguments that the proceedings were inadmissible because reasonable time limits had been exceeded.” The federal prosecutor’s request for arrest was not granted.

Johnson suffers from a serious liver disease, Flamme has been explaining for years. This was one of the factors raised to challenge the request for arrest. All parties are now awaiting the indictment division’s final decision on whether to refer the case to trial, which is expected in the coming weeks.