The Sahel has in the last decade or two been experiencing a multifaceted political crisis, marked by an Islamist rebellion and the installation of military regimes.

Mali was the first to be hit in 2011 with the rebellion in the north. Almost ten years later, Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta’s civilian regime fell, followed by a short transition before then vice-president Colonel Assimi Goïta took power on May 24, 2021. Next came the crisis in Burkina Faso, when street protests forced coup leader Blaise Comparé to resign. After a civilian government interlude, a new military junta took power in Ouagadougou on January 24, 2022. This same junta subsequently underwent changes that allowed Ibrahim Traoré to become the new head of state. Niger closed the cycle with the overthrow of Mohamed Bazoum on July 26, 2023.

This shared political and military history pushed the three countries towards solidarity, which the rest of West Africa no longer seemed to offer them. On September 16, 2023, they formed the Alliance of Sahel States (AES), a confederation of the three states, and withdrew from the treaty that created the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). On September 22, 2025, this pull-out momentum continued with the announcement of their withdrawal from the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC).

Although part of a logical continuum, this decision deserves closer examination.

Legal framework for withdrawal

The three AES states had successively ratified the Rome Statute. Mali was the first, on August 16, 2000. Niger followed suit on April 11, 2002, and Burkina Faso brought up the rear on April 16, 2004.

In accordance with Article 127 of the Rome Statute, it is clearly possible to withdraw from the ICC. However, such withdrawal must be notified to the Secretary-General of the United Nations, who is the depositary of the convention. Withdrawal only takes effect one year later, and it does not terminate obligations during the period when the State was a party, including during the year between notification and effective withdrawal. Finally, even if the three AES states are no longer parties, their nationals, including their leaders, could still be prosecuted—either for crimes committed during the period of ratification; or because jurisdiction is covered by a Security Council resolution; or because the crimes were committed on the territory of a State Party. Withdrawal is therefore governed by law and does not automatically terminate the Court’s jurisdiction over AES nationals.

A pro-Russian anachronism?

While withdrawal is legally possible, there is no obligation to justify it. However, in this case, the three States explained that their withdrawal was based on the fact that the Court had become an “instrument of neo-colonial repression in the hands of imperialism, thus becoming a global example of selective justice”.

The first observation is that the so-called “states of the South” are in the majority in the Assembly of States Parties to the ICC. So it is difficult for the Court to perpetuate colonial repression today. Furthermore, the Court’s actors are independent, and some are even African, notably Fatou Bensouda in the past (Deputy Prosecutor then Prosecutor) and Mame Mandiaye Niang (Deputy Prosecutor), not to mention the African judges and former Deputy Registrar Didier Preira. In addition, the ICC only exercises jurisdiction if the State has failed to do so. If a State does not want the Court to investigate crimes committed on its soil or by its citizens, it can punish them itself. The ICC is a court of complementarity. Finally, African states themselves requested and participated in the creation of the International Criminal Court, actively participating in its operation.

The second observation is that the criticism seems anachronistic.

Ten years ago, the Court was only dealing with African cases. The criticism was already unjustified for the reasons mentioned above, but it is even less justified today when citizens from other continents are targeted. It is enough to mention the arrest warrants against Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Russian President Vladimir Putin; the investigations on Afghanistan, which led to arrest warrants against supreme leader of the Taliban Haibatullah Akhundzada and Taliban Supreme Court president Abdul Hakim Haqqani; and the arrest of former Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte, who was detained in The Hague last March.

In short, the stated reasons are not justified. One has to believe there is more to it than meets the eye, hence the speculation about pro-Russian alliance. Catherine Maia and Pauline Equin, researchers in international law, highlight this link, noting a growing rapprochement between the AES states and Russia. And even if this is the aim, withdrawal from the ICC would not prevent the Court exercising jurisdiction over individuals, including members of the Wagner/Africa Corps group or national armies, if violations of international law are committed.

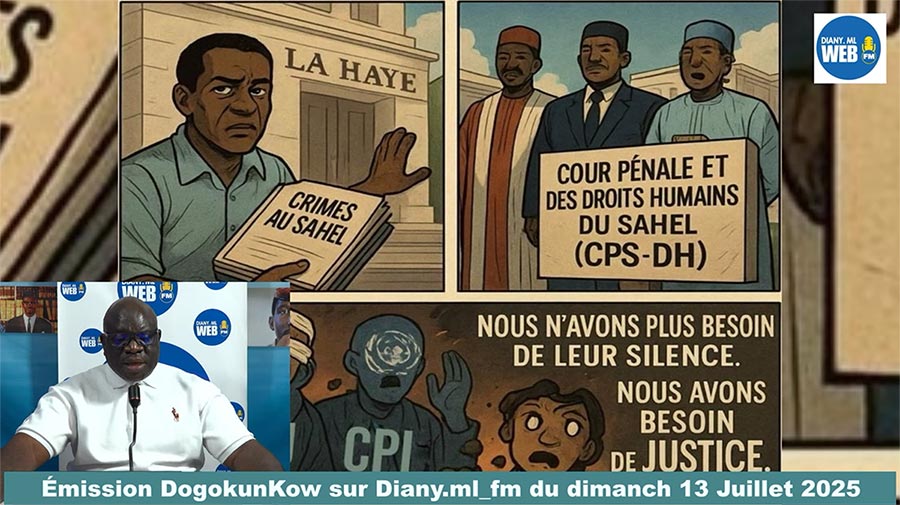

Vague plan for “home-grown justice”

If the motivation is misguided, the plan outlined in the communiqué seems even more so due to its unrealistic nature. Indeed, it states the AES members’ desire to “use home-grown mechanisms to consolidate peace and justice while reaffirming commitment to promoting and protecting human rights in line with their societal values and combating all forms of impunity”. It is clear that the AES intends to establish its own justice system to fill the void left by the withdrawal. However, we know that such a project poses a major challenge for Africa. The history that led to the Extraordinary African Chambers and the conviction in Senegal of Hissène Habré, former president of Chad, attests to these difficulties, which were overcome with mainly European funding as we wrote a good decade ago. Then there is the more recent history of the 2014 Malabo Protocol, which aims to extend the jurisdiction of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights to international crimes, but which no State has yet deigned to ratify, except perhaps Angola. This reinforces doubts about an African process. Finally, the substance of African or Sahelian “societal values” remains another major unknown.

Ultimately, this project is written like a campaign promise. Believing in it means running a high risk of disappointment, and the African peoples of the Sahel, more particularly those of the AES, cannot follow their leaders down such a path. Islamist rebellions commit atrocities. Military regimes also commit atrocities under the pretext of fighting these rebellions. And in both cases, the people are victims and need effective remedies to ensure that these international crimes are punished as soon as possible.

In concrete terms, there has been no withdrawal

The vision of a better future is an illusion here. But there is better news. To date, none of the three countries concerned has published a notification to the UN Secretary-General on the relevant portal. The latest notification concerning the Rome Statute concerns Hungary’s withdrawal on June 3, 2025. In concrete terms, this means that there has been no withdrawal, as the communiqué has no legal value. It is therefore just an intention that has not materialized to date, more than two months after it was expressed.

This raises questions about the seriousness of these States and what they were trying to say. It is to be hoped that reason will quickly prevail, as there is nothing to be gained from withdrawing from the Rome Statute, especially since universal jurisdiction remains a formidable and still available tool to sanction these crimes in third countries.

Sètondji Roland Adjovi is a lawyer specializing in international human rights law and international criminal law, and former member of the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention from 2014 to 2020. He is a former official of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) and the International Criminal Court (ICC). He has pleaded before the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights, before judicial authorities of international organizations, and before sports courts. He is currently pursuing his doctorate in law at the University of Quebec in Montreal (UQAM).