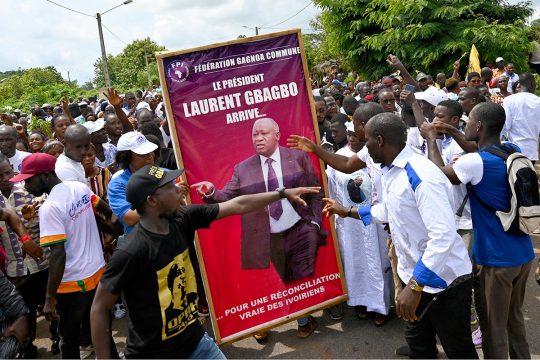

People arrested in Côte d’Ivoire after the fall of ex-president Laurent Gbagbo come from all walks of life, including former top civilian and military leaders, journalists, students and crop growers. How many are they? The government and opposition diverge widely on the numbers, and more arrests were made in the run-up to last year’s presidential elections.

“The officers are there, if I fall then so will they,” Gbagbo said as he addressed soldiers on August 7, 2010, the 50th anniversary of independence. But military leaders are not the only ones behind bars after Gbagbo’s fall in April 2011. Many people close to the Presidential Majority, a coalition of parties that supported the ex-president’s candidacy, have been arrested all across Côte d’Ivoire. Most of them are detained in the Detention and Correction Centre (MACA) in Abidjan.

Whether civilians or soldiers, all those arrested after the 5-month post-election crisis that left 3,000 people dead were close at one time or another to Gbagbo, his wife Simone or his party, the Ivorian Popular Front (FPI). They include not only well-known political personalities but also ordinary FPI activists or supporters, crop-growers, students, employees and even domestic help at the presidential residence. Then of course, there are journalists.

At least 400 political prisoners in 2014

How many people were thrown in jail after the victory of Alassane Ouattara? According to Amnesty International’s 2014-2015 annual report, the number of political prisoners in Côte d’Ivoire was then around 700. In any case they were not less than 400, according to a list submitted in 2014 to the Ivorian human rights commission (CNDHCI) by the Political Prisoners’ Wives and Families Association (AFFDO-CI), the main group representing victims of the post-election crisis.

Current FPI president Pascal Affi Nguessan confirmed this figure as he left a meeting with the Head of State on January 21 this year.

But in a public statement, Alassane Ouattara’s government said there were only 256 detainees, and refused to call them political prisoners. However, the figures might add up in view of the fact that many people arrested by the security services are in secret places of detention.

In general, judicial procedures are slow because of insufficient material and human resources. In addition, investigators often admit they do not know exactly what prisoners are accused of, according to a Justice Ministry source.

High profile prisoners include former Prime Minister Aké N’Gbo and former governor of the Central Bank of West Africa Dakoury Tabley, but also Gbagbo’s son Michel and his wife Simone.

The Simone Gbagbo case

Simone’s case is exceptional on several counts. The 65-year-old former First Lady is the only woman on the list. She was arrested along with her husband on April 11, 2011 and detained in Odienné for more than three years. She is wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC), which is trying her husband. However, she was brought before judges in Côte d’Ivoire in a trial that lasted from December 26, 2014 to March 10, 2015. The court sentenced her to 20 years in jail for “undermining state security, participating in an insurrectional movement and disturbing public order”. Seventy-eight other people were tried with her, including members of the last Gbagbo government and some 40 young men accused rightly or wrongly of being militiamen.

Despite the authorities’ promises of a fair trial, many observers criticized its weaknesses. After Simone Gbagbo’s sentence was confirmed by the Court of Assizes in March 2015, her lawyers went to the Supreme Court. However, the top court in the land rejected this final appeal on March 17, 2016, saying the judicial deadline had not been respected. The judge also said the final appeal should have been filed with the Appeals Court and not the Supreme Court.

Simone Gbagbo faces a new trial in her country for even more serious crimes related to the post-election violence, including murder. No doubt she would prefer to answer before the International Criminal Court alongside her husband and former Youth Minister Charles Blé Goudé.

More arrests before 2015 presidential polls

More opponents were arrested on the eve of last year’s presidential elections. They include Kouya Gnepa Eric, who was picked up by security forces after an attack by unidentified assailants on Grabo, southwest Côte d’Ivoire, in April 2015. The young man, tortured with several toes amputated and sick, died on December 5, 2015, amid the general indifference of his jailers.

Samba David was arrested with some 30 other people on September 13, 2015 for joining a banned march contesting Ouattara’s eligibility to run in the presidential elections. He was then sentenced to six months in jail in a trial his lawyers denounced as politically motivated. According to the latest information, he is still in jail, although his sentence was due to end on March 17.

Ouattara, although rejecting the term political prisoners, announced in his end-of-year speech on December 31, 2015 that he would use his constitutional powers to pardon or reduce the sentences of 3,100 people jailed in relation to the post-election crisis. These 3,100 people include personalities from the FPI and the National Coalition for Change who were all arrested in the run-up to the last election. The CNC is an association of 13 opposition parties and personalities created shortly before the the 2015 presidential elections with the aim of creating a strong opposition to Alassane Ouattara.

The opposition was quick to react, saying “Côte d’Ivoire needs rule of law not presidential pardons”.

Mamadou Koulibaly, former National Assembly president and now head of the Freedom and Democracy for the Republic (LIDER) association, says that at least Ouattara’s decision recognizes in a certain way the existence of political prisoners, something his government has been denying for the last five years. But he wonders from where the President will bring these prisoners, given that they have never officially existed. Why has Ouattara announced he will pardon so many prisoners when his government said recently there were only 256? In any case, in a recent meeting the FPI submitted to the Head of State a list of only 300.

Désirée Douati, President of the Political Prisoners’ Wives and Families Association (AFFDO-CI), deplores the lack of clarity on exactly who will benefit from this pardon.

Given that there are at least 500 political prisoners according to the opposition, the big question is who are the other 1,600 people concerned.

A senior Justice Ministry official who wishes to remain anonymous responded to Désirée Douati’s concern. According to this official, Gbagbo supporters arrested after the 2011 crisis will not be pardoned. Those concerned are rather common law prisoners, and indeed Ouattara made no mention in his December 31, 2015 speech of political prisoners. Here is what he said: “I have also decided, in conformity with Article 49 of the Constitution to use my power of “pardon” to waive some sentences fully or partially. This decision will allow thousands of prisoners to be freed immediately and others to see their sentences reduced. This measure applies to a total of 3,100 people.”