JUSTICEINFO.NET IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS

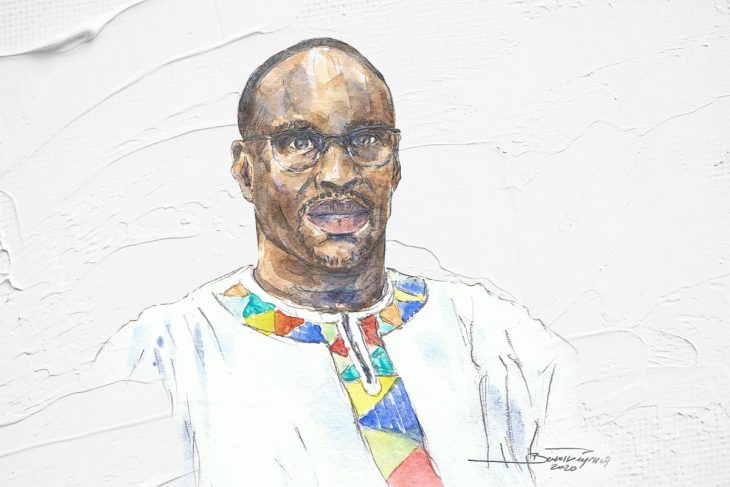

Essa Faal

Legal Counsel of Gambia’s Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission

Gambia’s Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission resumes its public hearings on January 20. For one year, the public face of the TRRC has been its legal counsel Essa Faal. He talks about the Commission’s achievements, its weaknesses, the controversy over ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda, and the factors which may explain why Gambia’s truth commission has been effective.

JUSTICEINFO.NET: You began your career as a state lawyer in the Gambia in the early 1990s. How was the judiciary functioning at the time Yahya Jammeh took power?

ESSA FAAL: I started my legal career at the same time Jammeh came to power through a military coup. Obviously, decrees were being passed frequently to try to bolster the power of the military junta. Nonetheless, the judiciary was not tampered with by Jammeh at the time. But there were some difficult instances that showed at the outset that Jammeh was interested in what the judiciary was doing and would take steps to interfere with the judiciary if it did not make decisions that were in his interest. Jammeh was a believer in the law as an instrument to secure compliance and obedience from the people.

And to exert oppression and abuse?

Yes. I mean if you look at the decrees that were passed, a lot of them have that effect.

Was there a moment when you felt that by remaining a state lawyer, you would be compromised?

No. I have had few instances wherein I was “tested”. There was a point Jammeh ordered that I should be transferred to the military to become the military lawyer. I refused. And nothing came out of it. And it was not only me. A colleague of mine, Dr Alagie Marong, who now works for the United Nations, was targeted to be moved as head of police prosecution. Both of us refused and nothing came out of it.

So you could refuse and still keep your job?

Yes. I suffered a few things, but nothing really serious. During those times, Jammeh wanted to flex his muscles. He tried to augment his power beyond what was authorized by law but he was not yet a dictator and sometimes he was challenged.

How do you reconcile what you say with all that we have heard from the Truth Commission about illegal arrests, torture, in the early years of Jammeh’s rule?

Yes, they were signs of dictatorial tendencies. But he did not have that dictator status. There was a system in place. There were institutions. He became a dictator subsequently when he was able to break the back or the will of these institutions to the extent that everybody in them became compliant.

When was that turning point?

It took years. In 1996 Jammeh was elected as president. That was a turning point because [prior to that] he was always trying to endear himself to the people because he wanted to win elections and remain in office. In the first few years after his election, Jammeh was still being reasonable. Then he became more entrenched in his position and did everything to further enhance his power. That was the beginning of the making of a dictator.

I left the Gambia at the end of 1997. We had military decrees that were still in the law books. But the new constitution was a normal Bill of rights that you would find in many African countries. The dictatorship was not there yet. Jammeh was still vulnerable.

We did not know how the disappeared people were killed. Many of us thought or believed the government’s propaganda that the people died as a result of crossfire or during fighting.

Up until 1997, as a prosecutor, did you have a clear sense of the human rights violations that were taking place?

We knew that there was a coup or an attempted coup in 1994 but we did not know what actually happened. We did not know how the disappeared people were killed. Many of us thought or believed the government’s propaganda that the people died as a result of crossfire or during fighting.

And the practice of torture against civilians who were arrested during that period, did you know about it?

You would hear rumblings that a particular individual may have been tortured in custody. But in those days, it wasn’t so prevalent. Also, a lot of these things happened in secret. People did not know. It was only much later that the National Intelligence Agency became a notorious institution for torture. It was only much later that they created the Drug Law Enforcement Agency which also became an instrument of oppression.

What made you accept the job as lead counsel of the Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC)?

I have done a lot of interesting and difficult cases but they were cases in foreign lands, with people I don’t know, environments that are not familiar to me. This case in Gambia is about me, it is about my own people, family and the future of my country. So to be asked to come and contribute in that is the greatest honour one could be given. To be quite candid, it is the easiest decision one would have to make. I would leave everything behind to come and do it.

Last June, you told us: “All of us contributed. Our silence contributed. We’ve seen the bad laws. Nobody would say anything and that encouraged the dictator. Jammeh kept pushing the envelope.” Do you see the job at the TRRC as a personal responsibility?

It is both a personal responsibility and a professional one. It is personal simply because this is something that hits home. The people who were arrested, beaten and tortured, a lot of these people are those that I know. It is also deeply personal because this deals with the future of my country.

What are the institutional failings that enabled the dictator to be created? We have a stake, all of us Gambians, to ensure that we do this [TRRC process] properly, so that every single Gambian would have a commitment to ensure that never again will we allow an individual to so dominate our society. This is going to pave the way for the rule of law in this country. We cannot afford to mess it up. And that is why it is a personal crusade and a professional responsibility.

it is our silence that strengthened and cemented Jammeh’s dictatorship.

But you also seemed to suggest that intellectuals like you should acknowledge their own responsibility.

Oh yes. The laws did not write themselves, Jammeh did not write them – we, the lawyers, wrote them. It is those who were in parliament who passed the laws. It is the police officers and public servants who implemented the law.

One of the worst laws to have ever been passed in this country is the law that allowed the president to do business. On the surface of it, it is not a big deal. But if you scratch deeper, it opened up a new world for Jammeh. He created an environment where business and entrepreneurship could not thrive because people were scared of him. Jammeh stamped out the competition and everything revolved around him. It is us who passed that law, it is us who sat back and watched him be a shark, prey on investors in all these sectors in which he was interested. So, it is our silence that strengthened and cemented Jammeh’s dictatorship.

I think Gambians have now appreciated the importance of their voice. They will no longer keep quiet.

How do you assess the progress of the work of the TRRC so far?

I think we have done extremely well. We have unearthed facts and violations of rights that people never thought happened in this country. Gambians used to say that violations did happen, but that they were done by foreigners. Well, now we know that it was us Gambians who were killing our brothers. Look at all the topics we have dealt with: we have demystified the July 1994 coup and how it happened; we have seen how Jammeh has attacked all those elements and authorities that could check on [him]; we have covered how Jammeh has attacked and muzzled the media; we have uncovered untold amount of torture; we have exposed how Jammeh has attacked members of the opposition [and] civil servants, unlawful arrests and detention; we have also exposed the use of Junglers [a death squad] to kill his perceived enemies. We have achieved a lot.

Now Jammeh is seen as an absolutely corrupt person. He is seen as a dishonest person. He is seen as a liar. He is seen as a murderer. He is seen, whether rightly or wrongly, as a rapist. He is seen as a thief. He is seen as an unpatriotic Gambian.

You talked about demystifying Jammeh. Can you explain?

There is a certain aura that always surrounds power and leadership and Jammeh had that. He managed to metamorphose from a mere 2nd lieutenant to a deified figure. A lot of people saw Jammeh as God. You recall images of him throwing water and imams and respected elders in society rushing to touch that water. They thought it cleansed or purified them. Embarrassing, isn’t it?

Such was [Jammeh’s] stature among some of our people. Who now looks at Jammeh in that same vein? Very few people. In fact, now Jammeh is seen as an absolutely corrupt person. He is seen as a dishonest person. He is seen as a liar. He is seen as a murderer. He is seen, whether rightly or wrongly, as a rapist. He is seen as a thief. He is seen as an unpatriotic Gambian.

Do you think that the evidence brought before the Commission today would be sufficient to prove him guilty of these crimes before a court of law?

His lieutenants, his minister of Defense [Edward Singhatey], his deputy chair Sanna Sabally, all of them implicated him in these murders as the person who ordered the killings, as the person who participated in a common plan in which they agreed to take no prisoners, to violate all norms of civilized behavior, to violate all the principles enshrined in the Geneva Conventions. So, yes I want to believe that before a court, he should be found guilty for murder.

If we move from the assessment of the regime into the work of the Truth Commission itself, what would you say are its weaknesses?

I think the area where we are not doing very well is reaching every part of the country in the best way possible. A lot of the hearings are in English and we are a multi-cultural society. That is the biggest drawback that we have. If we have the facility for everybody to hear and follow the proceedings in their own language, that would be fantastic. We are unable to do that.

There are also people who now need reparations. We don’t have the resources to be able to address the needs of all those people. The Commission is trying to address some of them. At the moment there are some of April 10-11, 2000, victims who were flown to Turkey for treatment. We wished the Commission would do more but that is not possible at the moment.

People who are mentioned before the TRRC for their alleged role in crimes are served a notice of adverse mention. Do you plan on sending such notice to Jammeh?

Obviously, Jammeh is not in the Gambia. The Commission will have to look into this issue and see whether to ask him to appear. I don’t know how this will play out. Nobody is above the law. It is a possibility. But it all depends on whether we have an opportunity to interact with him or not.

Do you think that if he remains out of reach, it will affect the outcome of the Commission?

No. the Commission will have sufficient basis to make its findings and its own recommendations. Ultimately, I think any serious Commission that looked into Jammeh’s activities would come with a recommendation for criminal prosecution for Jammeh or some form of accountability. That is to be expected.

Jammeh still has support in this country, but that is no reason for not prosecuting anybody. The question is whether applying the law will cause divisiveness in our society and whether that divisiveness will be harmful.

Do you think that the Gambia is prepared for Jammeh’s appearance before the Commission or for his prosecution?

Jammeh still has support in this country, but that is no reason for not prosecuting anybody. His supporters have a right to make their position known. This is a democracy. But the law must also take its course. The question is whether applying the law will cause divisiveness in our society and whether that divisiveness will be harmful. May be this is a political question for those in political authority to ponder. But if I have it my way, people who committed crimes in this country will be prosecuted in this country, for all to know that no matter how high, mighty or small you are, when you commit crime, you will be dealt with according to law.

But at the TRRC what you basically tell witnesses is that if they are truthful, apologize and commit to repairing the victims, they may not go to prison or be punished by a criminal court…

But that is precisely the point: the person must not necessarily go to jail. My watchword is the rule of law. And the law in this country is that if you appear before the Truth commission and you tell the truth, you do not seal yourself from responsibility and you express remorse, you may be recommended for amnesty. But we were talking about Jammeh. The TRRC Act is very clear: you cannot recommend amnesty for those who bear the greatest responsibility for the crimes. And it is quite obvious from the testimony of Sanna Sabally and the Junglers that Yahya Jammeh bears the ultimate responsibility. Therefore, he will not be entitled to any recommendation for amnesty. He would have to be accountable for these violations.

Also we cannot recommend amnesty for crimes against humanity. May be the Commission will find that some of these violations amount to crimes against humanity and therefore there would not be any recommendation for amnesty.

And these rules would apply to Jammeh’s former direct colleagues?

I would guess that they would fall under the same category. But still this is an assessment that the Commission will make.

What would do you prefer? That I don’t question them robustly and that they lie and get away with it? Or that they are questioned so robustly that at the end of the day they speak the truth?

You did give the Commission quite a prosecutorial nature that many truth commissions do not have. You are using interrogation techniques that are typical of adversarial criminal proceedings. Did you plan this in advance?

We have different categories of witnesses who appear before the Commission. You have the victims; they are questioned easily, they come and talk about their victimization and go. You have regular witnesses who are not adversely mentioned, they come and give their testimony and go. And then, you have the adversely mentioned people. A lot of them would want to come and lie.

What would do you prefer? That I don’t question them robustly and that they lie and get away with it? Or that they are questioned so robustly that at the end of the day they speak the truth? I would choose the latter. It is among persons adversely mentioned that we have had the highest percentage of confessions. And that happens not because they want to come and publicly confess to crimes [but] because they are questioned in a way that will elicit the truth out of them.

I don’t think truth commissions are just there to whitewash the truth. Truth commissions are there to find out the truth in a less controversial, adversarial way. If you look at what we do, we do not have any adversarial situation. In fact, these persons who are adversely mentioned are informed of their rights to bring a lawyer but none of them have chosen so far to do so. And in all honesty, they all leave [the TRRC] relieved. I have interacted with the Junglers: they feel relieved at the opportunity.

Yankuba Touray, one of the top leaders of the 1994 military coup, was arrested on charges of contempt for refusing to answer the questions of the Commission. The Justice minister then charged him with murder. This decision was criticized. How do you look at it?

People would hardly ever unanimously agree to a decision, especially a decision as controversial as this one. But the minister of Justice has a responsibility to uphold the law in this country. If the minister chooses to exercise his authority on a particular situation and think that under the circumstances, he needs to apply the law, I will not question that. And to be quite candid, I think it is a way out of the situation. You see, for contempt charges, they can go to jail for five days. Do you think that would have solved the problem? Many people would come here and sacrifice to go to jail for five days rather than come and speak the truth about certain things. Because it is uncomfortable to sit there and say: yes, I killed this person in such gruesome way. What could have happened if, say, Yankuba Touray was allowed to leave Mile 2 prison after five days or two weeks (in the event other charges of witness tampering succeeded)? May be some would think that the decision to charge him with murder, in the view of the evidence already presented, served a better example to the Gambians.

People come here and answer difficult questions because they feel that they have to. If they know that they should not, they would not.

Was it your conviction that if Touray was allowed to get away with it, it would affect the credibility of the Commission?

Yes. The thing is we would not want the Commission to be seen as a toothless bulldog. We tell people that when you come before the Commission, you have a duty to testify truthfully and you have a responsibility to answer questions. People come here and answer difficult questions because they feel that they have to. If they know that they should not, they would not. And then the Gambian people would not know the truth and millions would have been spent for nothing. It has happened in other countries. Some truth commissions have failed woefully.

Let’s to go back to the controversy around Fatou Bensouda, a Gambian national who is the current prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC). We have seen former ministers showing up to testify before the TRRC and admit personal or collective responsibility. Fatou Bensouda was a minister of Justice under Jammeh. Why would she be an exception and not be called to testify?

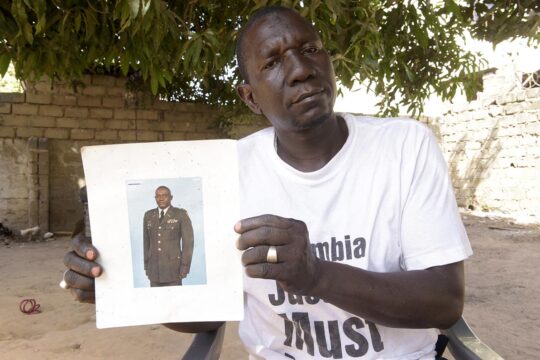

This is a storm in a tea cup. People are making so much noise out of nothing. Perhaps, it was a misunderstanding of the testimony. What happened was that we had a witness [Batch Samba Jallow] who explained that they were arrested, detained and prosecuted [in late 1995]. At some point, after about almost one year, the Ministry of Justice took over the prosecution and Fatou Bensouda happened to be the person with responsibility for the case. Typically, with any lawyer, the moment you are given a case file, what you look at is whether the charges are suitable or not. She looked at the charges and thought that perhaps a more sensible charge would be something different. She recommended to have their charge sheets amended. At the next hearing, she assessed the case and recommended for the charges to be dropped and the charges were dropped. So, what is the problem? What is her crime? I think Batch Samba Jallow made a grave error when he said that Fatou Bensouda was the architect of all their problems simply because he misunderstood the criminal justice system and how it functioned.

I would not sit there and support a narrative that would put responsibility for everything that happened to them to Fatou Bensouda when I knew exactly that she had nothing much to do with it.

Do not think we are just shielding Fatou Bensouda from responsibility. I know people will suggest that we have a good relationship. She has been my boss. I hold her to the highest esteem. But that is as far as it goes.

The fact is that between 1994 and 2000 Fatou Bensouda occupied positions where she got access to information and to Jammeh himself whom she served. Wouldn’t it be an interesting person to hear?

In the case that Batch Samba Jallow talked about, Fatou Bensouda was a principal state counsel acting as deputy director of public prosecutions. She was not a minister of Justice or special adviser to Jammeh. So the two periods are different.

But let me say something. We are doing an institutional hearing in which we are looking into the Ministry of Justice and some of the decisions that were made at the Ministry. We are not targeting any particular individual. We are going through all those years, look at all those laws that were passed or all those terrible cases that the Ministry of Justice worked on. And we will bring in the relevant individuals including the director of public prosecutions, attorney general or solicitor general to come and testify about certain things. If Fatou Bensouda happens to be one of those people who were involved in one or more of the areas that we may ultimately be concerned with, she will be called as a witness and testify.

Do not think we are just shielding Fatou Bensouda from responsibility. I know people will suggest that we have a good relationship. She has been my boss. She has been my senior at the Ministry of Justice. I respected her and I learned a lot from her. She was my senior at the ICC. We interacted directly. I hold her to the highest esteem. But that is as far as it goes. I have a professional responsibility to act properly and fairly. If in the course of our investigations, certain things come up which I think Fatou Bensouda will answer for, she would come and answer and I believe she will vindicate herself because I have always seen her as a good leader.

You have worked for many years as a prosecutor or defense lawyer at international tribunals, including the ICC. How has been your intellectual journey from criminal justice to a truth mechanism?

I have seen quite cathartic moments in truth commissions. To me, it reinforces their value. We have seen people come here, they got healing and closure just from the fact that they were given the opportunity to sit there and share their stories. We have seen situations where perpetrators and victims, on the spur of the moment, choose to come and embrace and try to forgive one another and reconcile. That shows that in the quest for justice, there are various strands that can be quite helpful and effective other than the criminal justice system. Truth commissions really do work sometimes.

And you did not know this before?

I was not so convinced. I was acting deputy general prosecutor in East Timor when they had their truth commission. It did not have much impact. At the level of my office, it did not shift our needle one inch. But in the Gambia, this is my first real exposure of a truth commission producing such interesting results.

Can you identify factors that may have made the process in the Gambia more effective?

In most countries, they want to make this a sociological or anthropological exercise. So, they keep lawyers away. In others, they want to make it a legal exercise and they bring in lawyers. And each of those versions will fail. I think it is about getting the right balance and the right institutional arrangements. In Gambia you have a nice mix. You have lawyers but it is not necessarily a criminal justice process. So, lawyers would help teasing out the truth without having such a legalistic process of lawyers’ wrangling. But the justice component is not completely removed: it has been partly postponed. That too helped.

You advocate for a combination of a truth-seeking and criminal accountability. Should it be, as we are seeing it in the Gambia, truth-seeking first and criminal accountability next?

Yes. That sequencing is very important.

The difficulty of getting the evidence is the crux of the matter. For dictatorships, it is more difficult to come out and gather the evidence. So, it is only a truth-seeking effort that will help bring these things out.

Truth commissions were born in the 1980s in Latin America and some scholars argue that they worked because they were well suited to the specificity of military dictatorship: information was covered up, murder was covered up and that is why truth-telling was relevant and efficient – as opposed, they say, to post-conflict situations where the truth has not been hidden. Is Gambia supporting this analysis?

It all depends on the process used for truth-telling. Yes, in a dictatorship where there are lot of secrets, a truth-seeking arrangement will really help. But even in post-conflict, a truth-seeking process can help. The difficulty of getting the evidence is the crux of the matter. For dictatorships, it is more difficult to come out and gather the evidence. So, it is only a truth-seeking effort that will help bring these things out because of exchanges for amnesty and things like that. In post-conflict situations, most of the time the victor will determine what the evidence is and come up with some form of victor’s justice.

Is there something you used to believe that you no longer believe?

Yes: forgiveness is not reconciliation.

You thought it was?

I thought it was. I have seen people say “I have forgiven them” but true reconciliation is much deeper than that. It goes way beyond forgiving the person. It comes with accepting that this thing has happened [and] that one has to move forward.

And at what level a truth commission can provide reconciliation?

At that point when people feel that they can now let go, that they have now moved on beyond the ills of the past. At the point where they see their previous adversary and not see an enemy.

Do you have evidence that this is what a truth commission can achieve?

I think it is possible to achieve that. That is our aim. It is a hope that I think is attainable.

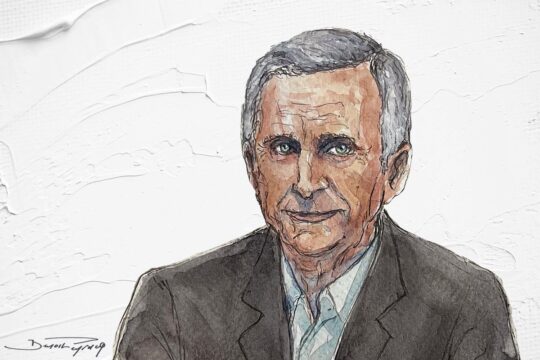

Interviewed by Mustapha K. Darboe and Thierry Cruvellier, JusticeInfo.net.

ESSA FAAL

Essa Faal is the Lead Counsel of the Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission in the Gambia. He began his legal career as a state counsel at Gambia’s Ministry of Justice in 1994. At the end of 1997, he was appointed as counselor for legal affairs at his country’s permanent mission to the United Nations, in New York. In 2000 he began a career as an international lawyer. He worked as a UN prosecutor in East Timor, where he was Acting Deputy General Prosecutor for Serious Crimes, then Chief of Prosecutions. From 2006 to 2018 he worked at the International Criminal Court, first for the Office of the Prosecutor in the Darfur Case, then as a Defense counsel in different cases, including Kenya and Libya.